More than half a century before the expulsion of Jews from Spain in 1492, hundreds of Jewish men, women and children on the Spanish Mediterranean island of Majorca were forcibly converted to Roman Catholicism. They were to be known as Xuetas, which may come from the word “Jueto,” or “little Jew.”

The converts became crypto-Jews, practising Judaism clandestinely while masquerading as Christians. They kept to themselves, married each other, and took surnames ranging from Pinya, Pomar, Miro and Pico to Cortes, Marti, Fortesa and Fuster.

Often stigmatized as the descendants of Jewish converts, they were generally regarded by Christians as cunning, untrustworthy and disgusting.

In 1688, 40 Xuetas tried to leave Majorca, the biggest island in the Balearic chain of islands, and were arrested. Thirty seven were burned at the stake before 30,000 spectators.

The Xuetas who chose to remain in Majorca were demonized and marginalized in popular culture, though they were permitted to grow prosperous as jewellers and traders. In recent years, their marginalization has diminished thanks to mass tourism.

Traces of Xueta gastronomy abound on the island in the form of empanadas, which were originally baked on the sabbath, and of ensaimadas, braided bread that resembles challah.

The turbulent saga of the Xuetas is recounted in Xueta Island, a fascinating documentary by Felipe Wolokita, Dani Rotstein and Ofer Laszewicki. It will be screened by the Hannukah Film Festival, which is being presented by Menemsha Films online from November 28 to December 5.

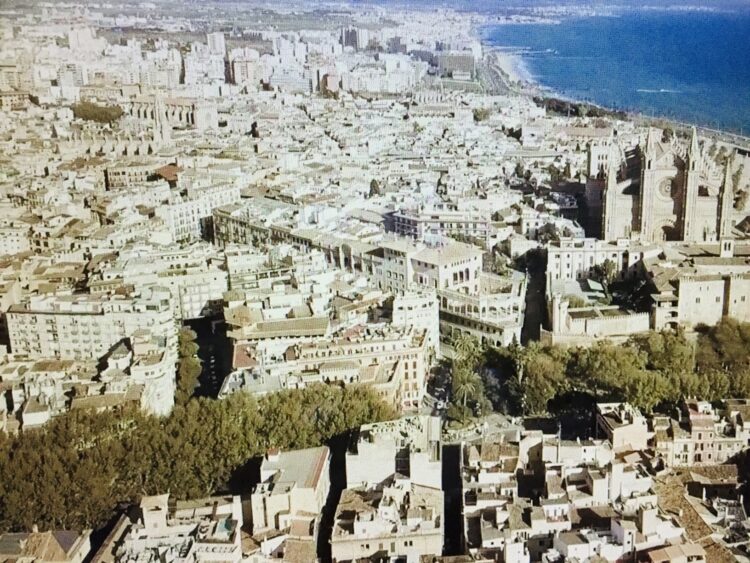

The movie revolves around several residents of Palma, the largest city in Majorca, which is known for its beach resorts, sheltered coves and limestone mountains.

Miquel Segura Aguilo is a jeweller and writer. Toni Pinya is a chef. Laura Miro Bonnin is a historian. Joan Manuel Segura is a philosophy teacher. Rotstein, one of the film’s director, lives in Palma and takes tourists around on tours.

A small number of Xuetas, like Aguilo and Pinya, have formally returned to Judaism and have gone as far as to change their names. According to Rotstein, an American whose mother is Israeli, most of the Xuetas are simply not interested in abandoning Christianity and adopting Judaism.

Segura, a young man of Xueta descent, believes that few of his contemporaries even want to learn about this element of their background. Bonnin, whose family refused to discuss its Xueta ancestry, is delving into her Jewish roots, though she does not identify with Judaism.

Aguilo admits he has very little in common with a Jew from Warsaw. “I’m a Majorcan Jew of Catalan and Spanish culture due to historical circumstances,” he says. Later on, he explains he was seeking an identity when he converted to Judaism.

Members of Pinya’s family were “extremely Catholic” so as to fend off potential hostility from Catholic neighbors. All he ever wanted was to be treated with respect, he adds.

Ari Molina, identified as Palma’s police chief, converted to Judaism 25 years ago and is now president of the Jewish community. The film does not explain his decision to convert to Judaism.

It is also vague regarding the known Xueta population in Majorca, but the figure seems to be something like 1,000 in a population of about 500,000.

In a postscript, Xueta Island discloses that a part-time rabbi, an Israeli, was hired this past June to tend to the religious and spiritual needs of the island’s Jews. He spends ten days a month in Majorca.

A Xueta by birth, his name was originally Nicolau Aguilo. Nowadays, he goes by the name of Nissan Ben Avraham. One of only two Xueta rabbis in the world, he’s the first rabbi from Majorca in nearly 600 years.

Historically speaking, Ben Avraham has come full circle.