When I was much younger, stamp collecting was a popular hobby among teenagers. Most of my friends collected them, and we eventually specialized by limiting ourselves to certain countries.

I saved and still have my stamps of Switzerland.

So it was a given that I’d visit the Smithsonian Institution’s National Postal Museum when I was in Washington DC earlier this year. Located on Massachusetts Avenue NE, across from Union Station, it’s an often- overlooked treasure, being somewhat out of the way.

Since its opening in 1993 in the historic City Post Office Building, it has celebrated America’s postal history from colonial times to the present, as well as that of countries around the world.

Six galleries explore topics ranging from the post office system in colonial and early America to the Pony Express to modes of mail transportation and artistic mailboxes.

The museum contains a vast collection of stamps, historic artifacts and interactive exhibits.

Visitors will discover the art of stamp making and design, and will marvel at the National Philatelic Collection, which features more than 5.9 million items.

At interactive displays flanking a large globe, visitors explore examples of how stamps reflect their countries of origin and connect people, places, and cultures worldwide.

One display showcases some of the most scarce and famous stamps from 24 countries on six continents. Nearby, 50 pullout frames present almost 800 stamps, one from every country that has ever produced stamps, including many countries that no longer exist.

The museum owns three “Doar Ivri” single stamps with tabs. When Israel issued its first stamps in 1948, the new nation had not yet decided on a name. Hence their inscriptions read Doar Ivri, meaning Hebrew Post.

These high value stamps have their tabs (printed pieces of sheet margin), which many collectors removed to fit the stamps in albums.

Canada and the United States jointly issued a stamp to honor the 1959 opening of the St. Lawrence Seaway. During the printing of the Canadian stamp, a few sheets were fed into the press upside down –inverting the image. The inverted stamp here is one of only 24 that were actually used.

Among the American stamps displayed is the “inverted Jenny,” the 24-cent 1918 United States airmail stamp with the airplane erroneously depicted upside down. It is the most valuable U.S. stamp.

The biplane featured in the design is the famous Curtis JN-4-H “Jenny,” modified by replacing the front cockpit with a mail compartment. The error occurred at the Bureau of Engraving and Printing during the week of May 6- 13, 1918: one sheet of 100 stamps with an inverted image of a blue airplane escaped detection.

Because the bicolor stamp was printed from two printing plates (one for the carmine-colored stamp frame, one for the blue vignette), the error resulted from the misfeeding of sheets or the misorientation of one of the plates. Only one sheet of 100 inverted center stamps was sold, and no other examples have ever been discovered.

In May 2016, a particularly well-centered Jenny invert, graded XF-superb 95 by Professional Stamp Experts, was sold at an auction in New York for $1.35 million.

The “inverted Jenny” is the most requested postage stamp for viewing by visitors at the museum. (Not being rich, I had to make do with buying a beautiful t-shirt with the” inverted Jenny” on it.)

Another exhibit, on view until next March, explores the life of Alexander Hamilton (1755-1804) through original mail sent and signed by him in his role as the first Secretary of the Treasury and through portraits of him and his contemporaries on postage and revenue stamps.

The experience is augmented by in-gallery interactives and educational programming, all coinciding with the Washington dates of the national touring version of Hamilton: An American Musical.

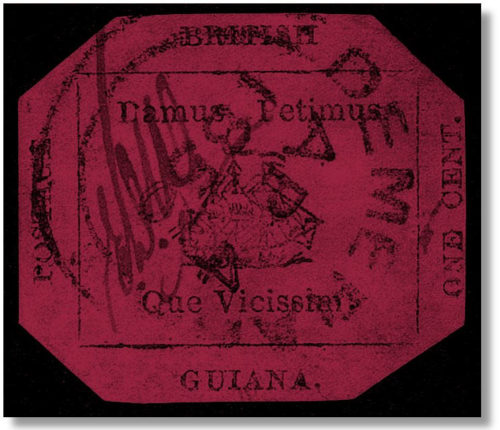

Also on view when I was there, behind unbreakable glass in a climate-controlled display case, was the world’s rarest and most valuable postage stamp, the 1856 British Guiana One-Cent Magenta. That alone was worth the visit.

In January 1856, the colony of British Guiana in South America issued a small number of one- and four-cent stamps for provisional use while the postmaster waited on a shipment of postage stamps from England. Multiple copies of the four-cent stamp have survived, but the one-cent stamp is the only one of its kind in the world.

It features a sailing ship along with the colony’s motto, “We give and expect in return,” in Latin.

It breaks records every time it sells. In June 2014 it sold for $9.5 million, the most ever paid for a stamp at auction. On loan from owner Stuart Weitzman until this coming December 2, it has spent most of its 162 years behind bank vault bars, appearing only on rare occasions. The National Postal Museum’s display has been the One-Cent Magenta’s longest and most publicly accessible exhibition ever.

The museum also houses an atrium sporting a 90-foot-high ceiling. Three airmail planes hang overhead, while a stagecoach from 1851 and a 1932 Ford Model A postal truck also adorn the room. You can also browse through a 1920s-style post office.

There’s plenty to see in Washington, of course, but if you’re interested in philately, this is a must-see place to visit.

Henry Srebrnik is a professor of political science at the University of Prince Edward Island.