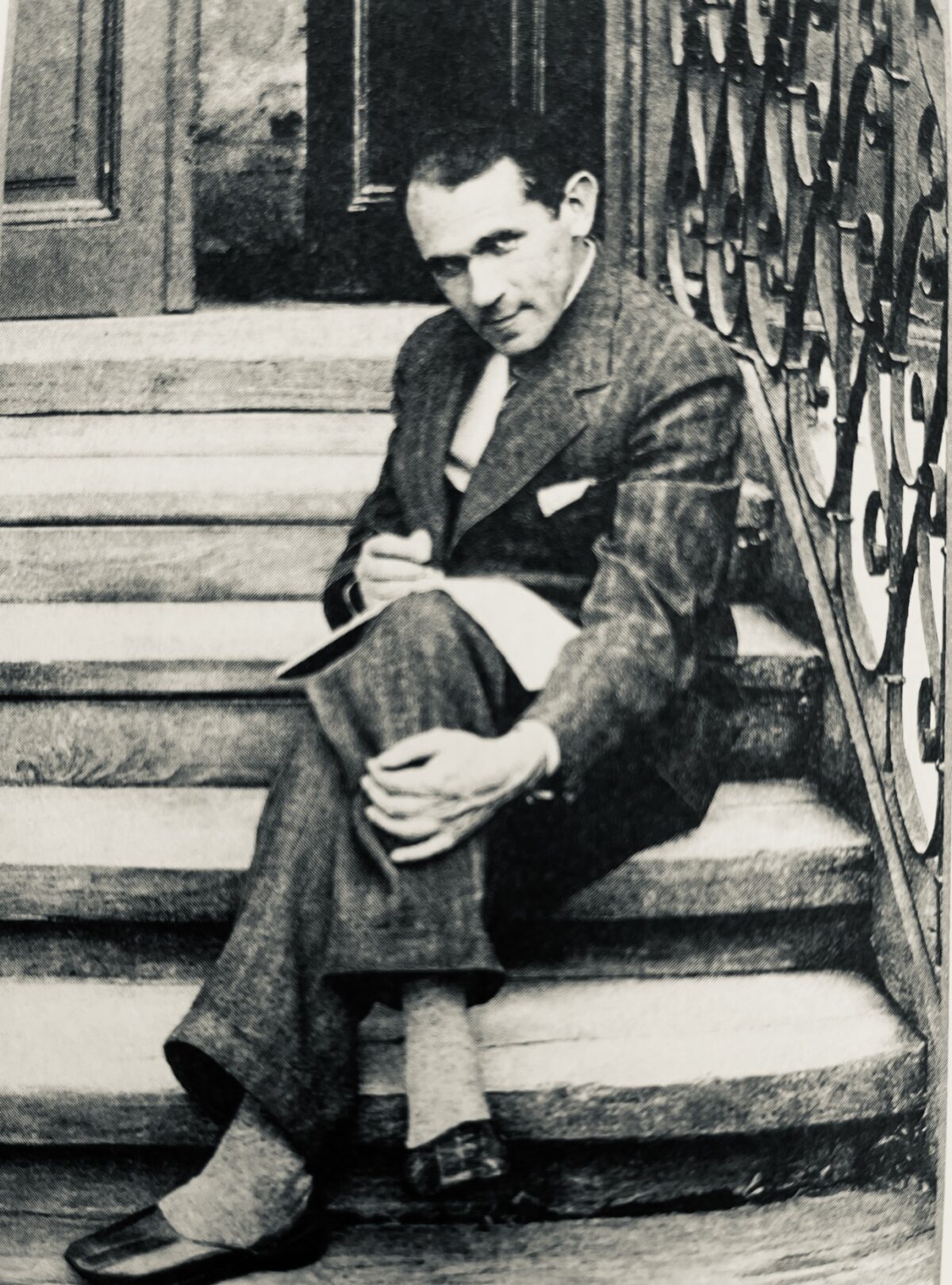

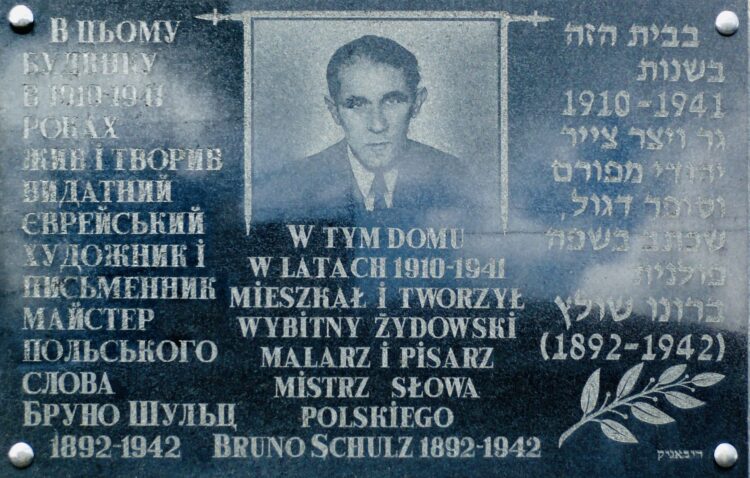

Bruno Schulz, the great graphic artist and luminous writer, was a displaced and uprooted person par excellence. He was born an Austrian during the Austro-Hungarian empire. He held Ukrainian and Polish citizenship during the duration of the West Ukrainian People’s Republic and the Second Polish Republic. And he died as a persecuted Jew during the Nazi occupation of Poland.

Most of all, he inhabited the Republic of Dreams, the mythical land of his incredibly fertile imagination.

Hailed by the Yiddish novelist Isaac Bashevis Singer as “one of the most remarkable writers” of his generation, he was a “virtuoso of language and image,” as Benjamin Balint succinctly describes him in his superb biography, Bruno Schulz: An Artist, A Murder, and the Hijacking of History (W.W. Norton and Company).

Murdered by a German soldier in 1942, Schulz produced two volumes of short stories which, as Balint observes, “mapped the anxious perplexities of his time”: Cinnamon Shops (1934), published in the United States as The Street of Crocodiles, and Under the Sign of the Hourglass (1937), both of which were written in fluid Polish prose and “touched by the divine finger of poetry.”

Schulz is equally renowned for the murals he was coerced to paint in Drohobych, his hometown in what is now Ukraine, by an SS officer named Felix Landau. These gaily-colored murals, depicting unflinching freedom, were painted on the walls in an SS villa. They were forgotten after the war, rediscovered by two German filmmakers decades later, and smuggled to Israel by three Israelis employed by Yad Vashem, the Holocaust memorial/research center in Jerusalem.

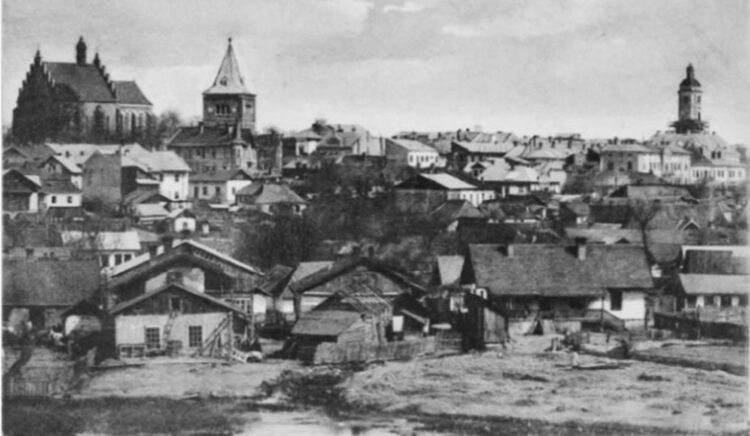

The youngest child of a bourgeois family, Schulz was born on July 12, 1892 in Austrian-annexed Galicia, a poverty-stricken province which had been Polish territory until the first partition of Poland in the late 18th century.

Drohobycz, his birthplace and a satellite of Lwow, the regional capital, was an industrial city economically dependent on the production of salt and crude oil. One of the Jewish families in the oil business there were the Arnolds, whose daughter, Aliza, married her fiancé, Menachem Begin, in Drohobycz in May 1939.

Practically a Jewish city, 40 percent of its residents were Jewish. Thirty percent were Catholic Poles, while 30 percent were ethnic Ukrainians. Seized by the West Ukrainian People’s Republic in November 1918, it was captured by Poland less than a year later.

Drawn to the visual arts, Schulz dreamed of being a painter. In 1920, he enrolled in the School of Fine Arts in Warsaw. Denied admission to the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts, he returned to Drohobycz, where he began teaching arts and crafts, draftsmanship and woodworking at the high school he had attended from 1902 to 1910.

Schulz regarded teaching as a torment, but he remained in his job for 17 years, struggling with depression. Students, though, were enchanted by his fairy tales, which he recounted in exquisite Polish. “Schulz had long concealed his literary ambitions, (and) beset by insecurities, he had written in isolation for the desk drawer,” writes Balint.

Cinnamon Shops was published with the encouragement of Zofia Nalkowska, a member of the Polish Academy of Literature, the vice-president of the Polish PEN Club, and an editor with the prestigious Roj publishing house. Seven years older than Schulz, she became his lover. Schulz’s second book, Under the Sign of the Hourglass, was illustrated by 33 of his drawings.

As Balint points out, Schulz had romantic liaisons with two other women — Debora Vogel, an academic who had earned a PhD in philosophy with a dissertation on Hegel’s aesthetics, and Josefina Szeklinska, a teacher whose family had converted from Judaism to Catholicism.

During the early 1930s, Schulz painted a colorful portrait of Jozef Pilsudski, the first chief of state of Poland, which regained its independence and sovereignty in 1918. In the wake of his death in 1935, a wave of antisemitism swept through the country. Schulz was not surprised by the resurgence of Polish bigotry. In 1936, one of Poland’s leading writers, Sofia Kossak-Szczucka, had declared, “Jews are so terribly alien to us, alien and unpleasant, that they are a race apart. They irritate us and all their traits grate against our sensibilities.”

With the outbreak of the war in 1939, German invading troops reached Drohobycz on September 11. Less than two weeks later, the Red Army, as per the Soviet Union’s recent non-aggression pact with Germany, rolled into Drohobycz.

The Germans returned on June 30, 1941 after invading the Soviet Union. Ukrainian nationalists, having accused Jews of collaborating with the Bolsheviks, unleashed a pogrom. Starting on July 15, Jews in Drohobycz were required to wear a blue Star of David on their left arms. Antisemitic restrictions and mass shootings followed. Schulz and his family were forced to vacate their home and move into a shanty in the Nazi ghetto, which was inhabited by 12,000 Jews suffering from hunger, cold and disease.

By March 1942, the Nazis had begun deporting Jews to the newly completed Belzec extermination camp.

At around this juncture, Felix Landau, a sadist who appreciated Schulz’s talent as a painter, established “a relationship of protection and predation” with Schulz. Landau, a Viennese whose stepfather was a Galician-born Jew, designated Schulz as a “necessary Jew” after he ordered him to paint his portrait and create murals in several buildings in the city.

Landau, who hated his Jewish-sounding name, joined the Nazi Party in Germany in 1931 and the SS in 1934. During the initial weeks of Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union, he volunteered for service in a mobile killing squad which perpetrated massacres in the Lemberg district. He arrived in Drohobycz on July 7, 1941.

Schulz was killed by Karl Gunther, an SS sergeant, on November 19, 1942 as he returned from an errand. He was shot in the head at point-blank range. On that day, upwards of 230 Jews in Drohobycz were fatally shot in a Nazi orgy of violence.

Half a year after Schulz’s murder, the Gestapo liquidated Drohobycz’s ghetto, killing its remaining 2,300 Jews in a nearby forest. In July 1943, the city was declared “cleansed of Jews.”

Russian forces recaptured Drohobycz on August 6, 1944, and it was incorporated into the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, which suppressed his books as products of bourgeois decadence. “His legacy, like his half-forgotten murals, lived on only in the memory of his few surviving students,” says Balint.

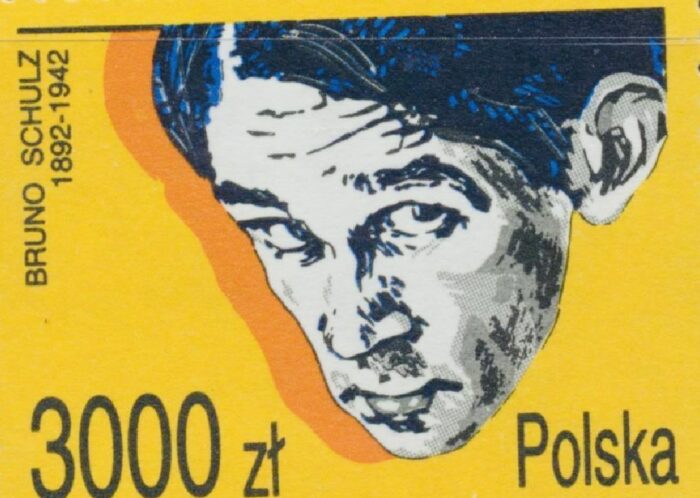

In post-Stalinist Poland, however, Schulz’s books reappeared, prompting a spate of international translations of his works in the 1960s. The revival of Polish interest in Schulz was spearheaded by the poet Jerzy Ficowski, one of his admirers. In 1967, a museum in Warsaw mounted the world’s first major exhibition of Schulz’s drawings. And in 1974, the first conference in Poland dedicated to him took place at the University of Silesia. In 1988, Schulz’s writings were canonized in Poland’s National Library. And in 1992, Poland marked the 50th anniversary of his death with a postage stamp and a conference at Jagiellonian University in Krakow.

New Ukrainian translations of Schulz’s stories came out in 1992, and the first conference in Drohobycz devoted to his work took place in the same year.

Sixty of his drawings were exhibited for the first time in the United States in New York City’s Academy of Arts in 1988.

Two German filmmakers from Hamburg who were fascinated by Schulz, Christian Geissler and his son Benjamin, visited Drohobycz in 2000 with the intention of making a documentary about him. They had learned that Schulz’s murals could be found in an apartment building inhabited by an elderly couple.

Upon discovering the murals, Benjamin Geissler notified several Ukrainian government officials, including the mayor of Drohobycz. Geissler then launched a campaign to raise funds to build a museum in that building.

Unbeknownst to the Geisslers, Yad Vashem dispatched three agents to Drohobycz in May 2001 on a top-secret mission to pry the murals from the walls of the apartment and smuggle them to Israel. The operation was commanded by Yad Vashem’s chairman, Avner Shalev, the son of Polish immigrants, and approved by Israel’s prime minister, Ariel Sharon.

The removal of the murals, a violation of international conventions, was denounced by Ukraine and Poland.

Yehuda Bauer, the Israeli Holocaust scholar, said he recognized “the legitimacy of the Polish struggle for keeping the artwork of Schulz.” But as he added, “Schulz was murdered because he was a Jew, not because of his Polish citizenship. In the eyes of his Polish contemporaries, he was a Jew, not a Pole … I think that he was killed for his Jewishness, there its every justification for his work to be kept by Yad Vashem …”

Shalev, in a letter, justified Yad Vashem’s unilateral move on the grounds that the murals were in a severe state of deterioration, and that the mayor and his deputies had approved of it. “Yad Vashem’s conservation experts saved the fragments from further decomposition and carried out eminent restoration work,” he wrote.

Yad Vashem, in 2009, placed the murals on public display.

In 2008, Israel and Ukraine reached an agreement that the murals would remain in Yad Vashem “on loan” for 20 years, after which the “loan” could be renewed every five years.

Two years earlier, a small copper plaque, designed by a Polish artist, was placed at the site of Schulz’s murder. It was pried loose from the pavement and sold as scrap metal in 2008 by an illiterate local who had never heard of Schulz. A copy was installed in its place in 2010.

Ninety Jews live in Drohobycz today, a far cry from the days when almost half its population was Jewish. They are the last living links to a community that produced a figure as renowned as Schulz.