Avi Shlaim’s intriguing, ideologically-driven book, Three Worlds: Memoirs Of An Arab Jew (OneWorld), is a bitter-sweet autobiography of an accomplished Iraqi Jew who left his homeland under duress, an impassioned look back at Iraq’s lost Jewish community, and a stinging critique of Zionism and Israel.

He acknowledges that this is a “revisionist tract,” a “challenge to the widely accepted Zionist narrative” of Jews in Arab lands.

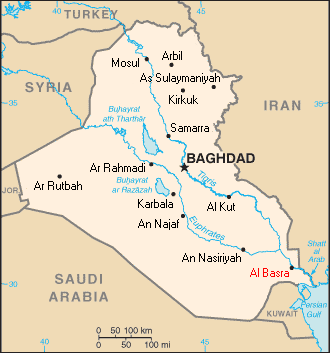

An emeritus professor of international relations at St. Antony’s College, Oxford, he was born in Baghdad in 1945, moved to Israel with his family in 1950, and studied in Britain from the age of 16. He returned to Israel to join the Israeli army, and then went back to Britain to resume his education. He has since lived there.

As an academic, Shlaim specialized in the Middle East, writing a succession of books about the Arab-Israeli conflict, notably The Iron Wall and Collusion Across the Jordan, both of which were critical of Israel.

A Sephardi Jew despite his Germanic surname, Shlaim describes himself as “an Iraqi boy” who was raised in “a land of Europeans,” which inculcated in him an inferiority complex. As a youth in the newly established state of Israel, he “unquestionably accepted the social hierarchy that placed European Jews at the top of the pile and the Jews of the Arab and African lands at the bottom.”

At that point in his life, he had no idea that being an Iraqi Jew might one day be advantageous, inasmuch as he could “transcend national stereotypes” and take “a more balanced, if not detached, view” of Israel’s dispute with the Palestinians in particular and with the Arabs in general. In other words, he would develop an ability “to see beyond simple certitudes,” acquire “a more nuanced” perspective, and become aware of “the possibility of peaceful Arab-Jewish coexistence.”

He hails from an upper-class family that was displaced by the combined pressures of Iraqi xenophobia, the birth of Israel, the dispossession of the Palestinians, and the first Arab-Israeli war. “We were part of the mass exodus of Jews from Iraq to Israel. Our departure from our homeland was due to forces that were completely beyond our control, and even beyond our comprehension.”

“Our family fortunes mirrored that of an entire community, one that was uprooted from a world in which we felt at home to one in which it had to make painful adaptations,” he adds. “We were Arab Jews. We … were well-integrated into Iraqi society. We spoke Arabic at home, our social customs were Arab, our lifestyle was Arab, our cuisine was exquisitely Middle Eastern, and my parents’ music was an attractive blend of Arabic and Jewish.”

In this vein, he goes on to say, “We were Iraqis whose religion happened to be Jewish and as such were were a minority, like the Yazidis, Chaldean, Catholics, Assyrians, Armenians, Circassians, Turkomans and other Iraqi minorities.”

The Iraq between the two world wars was a nation of “pluralism and coexistence,” he notes. And the Jewish connection to Iraq/Babylon predated the rise of Islam. “We did not feel any affinity with the Zionist movement,” he says, branding it as a “settler colonial” phenomenon. “We experienced no inner impulse to abandon our homeland to go to live in Israel.” Once in Israel, he writes, his family was “relegated to the margins.”

In his opinion, Iraqi Zionism was not “a home-grown product but a foreign ideology” propagated by Zionist officials from Palestine. He believes that Britain, in the 1917 Balfour Declaration, had “no legal, political or moral right to turn over the land of one people to another.” Obviously, Shlaim thinks that Jews have no historical rights to Israel, which is a monumental fallacy.

He admits that Iraqi Jews experienced “stresses and strains” and notes that they were the victims of a pogrom in Baghdad in June 1941, but his counter argument is that they were a protected minority, enjoyed equal rights, were not forced into ghettos, and played a prominent role in Iraq.

But having become entangled in the conflict between Zionism and Arab nationalism and having been caught in the crossfire between Jews and Arabs over Palestine, Iraqi Jews were increasingly seen as a sinister fifth column and singled out for harassment and persecution. “The twin currents of Arab nationalism and Zionism made it impossible for Jews and Muslims to continue to coexist peacefully in the Arab world after the birth of Israel.”

He claims that only a “small minority” of Iraqi Jews supported the aims of the Zionist movement, while the vast majority regarded Iraq as their homeland and wished to stay.

To Shlaim, Zionism spawned a state that would be culturally and politically aligned almost exclusively with the West. Arabs regarded Israel as “an extension of European colonialism” in the Middle East.

Shlaim places the Jews of Iraq within the context of Iraqi history.

During the long Ottoman period, which ended in 1918, minorities were subjected to a host of discriminatory restrictions, but governed themselves under the millet system.

With the advent of British rule under a League of Nations mandate, Britain installed Prince Faisal, the leader of the wartime Arab Revolt, as Iraq’s monarch. Previously, he had been king of the Arab Kingdom of Syria, which was violently overthrown by France.

Iraqi nationalists opposed the British presence, partly because Christians and Jews, among others, were given preferential treatment. Jews welcomed the arrival of Britain, thinking it would bring security and stability to a fractious nation, expand commercial opportunities, and ensure equal treatment for minorities.

During the British era, Jewish merchants controlled the import and export trade and Jews constituted the “backbone” of the economy. Iraq’s first finance minister, Sir Sassoon Haskell, was Jewish. According to Shlaim, he was averse to Zionism, fearing that a Jewish state in Palestine would create insurmountable problems for Jews in the region. Jews were also prominent in every branch of Iraqi culture, from music to journalism.

Jews generally avoided participation in pan-Arab causes. He acknowledges that some Iraqi Muslims, especially on the right, regarded them as enemies of their national aspirations.

Although the mandate formally ended in 1932, Britain exerted control over Iraq. King Faisal died a year later, and his death marked the end of a liberal, religiously pluralistic Iraq. He was succeeded by his only son, Ghazi, who hated the British. Ghazi was under the influence of the pro-British prime minister, Nuri al-Said, the dominant figure in Iraqi politics until his gory death in 1958. During Ghazi’s rule, Iraqi nationalists grew more assertive and outspoken, and German influence blossomed.

The first military coup in the modern Arab world took place in Iraq in 1936, and from that point onward, minorities faced mounting discrimination. Hundreds of Jews were dismissed from the civil service in the name of reform and budget cuts and informal quotas limited Jewish enrollment in state schools and colleges.

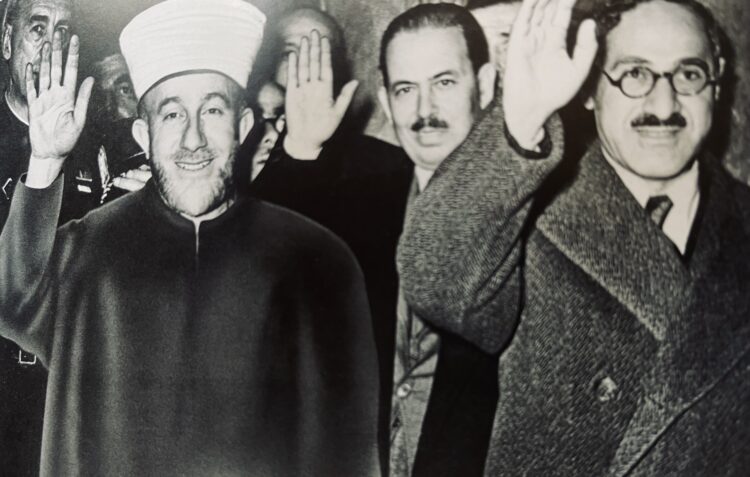

Ghazi was killed in a car accident in 1939, and his four-year-old son, Faisal II, officially succeeded him. In practice, Iraq was ruled by his pro-British uncle, Prince Abd al-Ilah. Following this turn of events, the German propaganda machine in Baghdad and the grand mufti of Jerusalem, Haj Amin al-Husseini, contributed to the dissemination of antisemitic sentiment in Iraq.

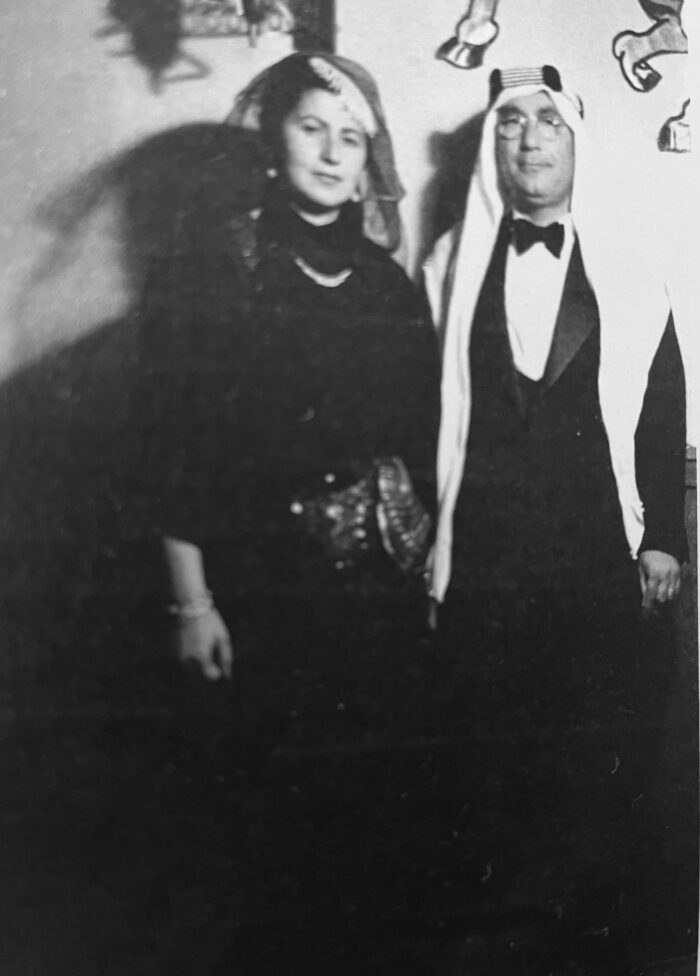

Shlaim’s parents, Yusef and Saida, were brought together in an arranged marriage in Baghdad in 1942. He was 41. She was 17. Their relationship was stormy and ended in divorce in Israel. Yusef prospered as a businessman and lived near the Tigris River in an elegant three-story house with a lush garden.

They were married in the wake of the farhud, the pogrom which resulted in the deaths of 179 Jews. It unfolded against the backdrop of nationalist fervor promoted by Rashid Ali al-Gaylani, a pro-German pan-Arabist who had been pressured to resign as prime minister in January 1941.

On May 29 of that year, he and his followers fled to Iran and from there on to Germany. Law and order broke down in Baghdad, leaving a vacuum that was exploited by nationalists, who perceived Jews as friendly to the British. Civilians and soldiers attacked Jewish homes and shops, looting, raping, murdering and injuring hundreds of Jews.

The farhud shocked Iraqi Jews. “There had been no other attack on the Jewish community in recent centuries,” says Shlaim. Ultimately, most Jews saw it as an aberration, particularly after the government offered compensation to its victims. To Zionists, though, it was an impetus to emigration.

It shook Shlaim’s family to the core, prompting his mother to wear an abaya, the loose black garment worn by pious Muslim women.

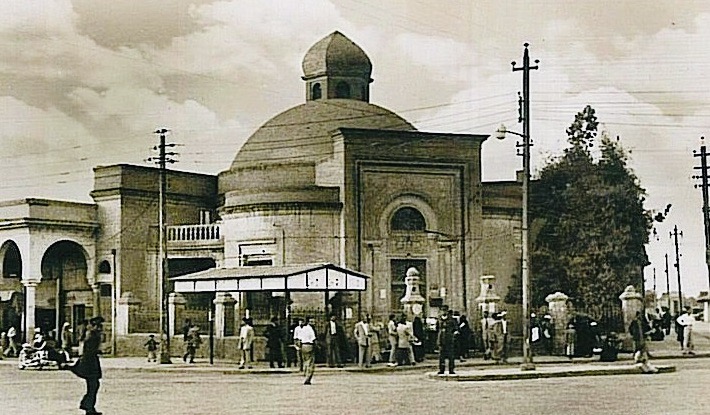

Recalling his childhood in Baghdad, Shlaim paints a rosy picture of his secular family’s relaxed and comfortable lifestyle and of a cosmopolitan, multiethnic city of mosques, churches and synagogues in which Jewish, Muslim and Christian neighbors mingled and enjoyed cordial relations.

Shlaim claims that the 1947 United Nations Palestine partition plan was opposed by Iraq’s major Jewish organization. “The majority of Iraqi Jews saw themselves as Iraqi first and Jewish second. They feared that the creation of a Jewish state would undermine their position in Iraq.”

With the passage of this resolution, he says, “the distinction between Jews and Zionists, so crucial to interfaith harmony in the Arab world, was rapidly breaking down.”

The Iraqi army’s participation in the 1948 Arab-Israeli war fuelled anti-Jewish animus in Iraq. “Whether or not they sympathized with Zionism, Iraqi Jews were widely suspected by the general public of being secret supporters of Israel.”

The Arab defeat in the war emboldened the Iraqi government to whip up popular hysteria and suspicion against Jews. Zionism was declared a criminal offence. Jews were sacked from government jobs. Jewish merchants were denied export licences.

Shafiq Ades, the wealthiest Jew in Iraq, was accused of false charges of selling weapons to Israel and supporting the Communist Party. He was hanged and his family was ordered to pay a very hefty fine. His execution set off alarm bells in the Jewish community.

In March 1950, the Iraqi Parliament passed legislation empowering the government to issue exit visas to Jews who wanted to leave. They had to relinquish their Iraqi nationality and waive their right to return to Iraq. Jews who chose to stay were assured of equal rights with Muslims.

The driving force behind Iraq’s policy was the prime minister, Tzawfik al-Suwaydi, who as a child had been enrolled at a Jewish school. In Iraq, he had a reputation for being well disposed toward Jews.

Jews who had an ambivalent attitude toward emigration were pushed toward leaving by five bombings in Baghdad targeting Jewish businesses and a synagogue. Shlaim charges that three of them were the work of Zionist operatives. The remainder were carried out by a Sunni Muslim criminal of Syrian origin and the Istiqlal Party, which was antagonistic to Jews.

Shlaim compares these false flag bombings to the Israeli operation in Cairo in the mid-1950s during which Egyptian Jews at the behest of the Mossad planted bombs in public places and at a U.S. cultural center to generate animosity between Egypt and Western powers.

In Shlaim’s judgment, the years 1950-1951 marked a “cataclysmic” period for Iraqi Jews. “In the space of just over a year, nearly the entire community left behind their ancient homeland and made their way to the young and impoverished state of Israel.”

Out of a total of 135,000 Jews, 125,000 immigrated to Israel. “A Jewish presence that went back two and a half millennia to the destruction of the First Temple and the Babylonian exile came to a sudden and painful end. We had lived in Iraq for generations, we had deep roots in the country, we were well integrated socially, my father’s business was thriving, and we had no desire to change either our identity, our nationality or our lifestyle. Going to Israel was a leap in the dark for which we were utterly unprepared.”

Shlaim, his mother, maternal grandmother and two sisters left Iraq on July 21, 1950. They departed as British citizens because his grandmother had acquired British nationality when she married her husband. They flew to Cyprus, and after a two-month stay in Nicosia, continued their journey by boat to Haifa. Shlaim’s father, who had Iraqi nationality, joined them about 18 months later. Having smuggled money out of Iraq, they were able to survive financially in Ramat Gan, a suburb of Tel Aviv where they purchased a modest flat. Much to Shlaim’s father’s bitter disappointment, his two business ventures in Israel failed, leaving him disappointed and broken.

Shlaim did not feel at home in an Ashkenazic environment in Israel. “I carried a chip on my shoulder because I was an Iraqi. I did not experience direct discrimination … but I could not rid myself of the subjective feeling that I was not as good as the Ashkenazic kids in my class … I was particularly ashamed of speaking Arabic in public, because Arabic in Israel was considered an ugly language … the language of the enemy.”

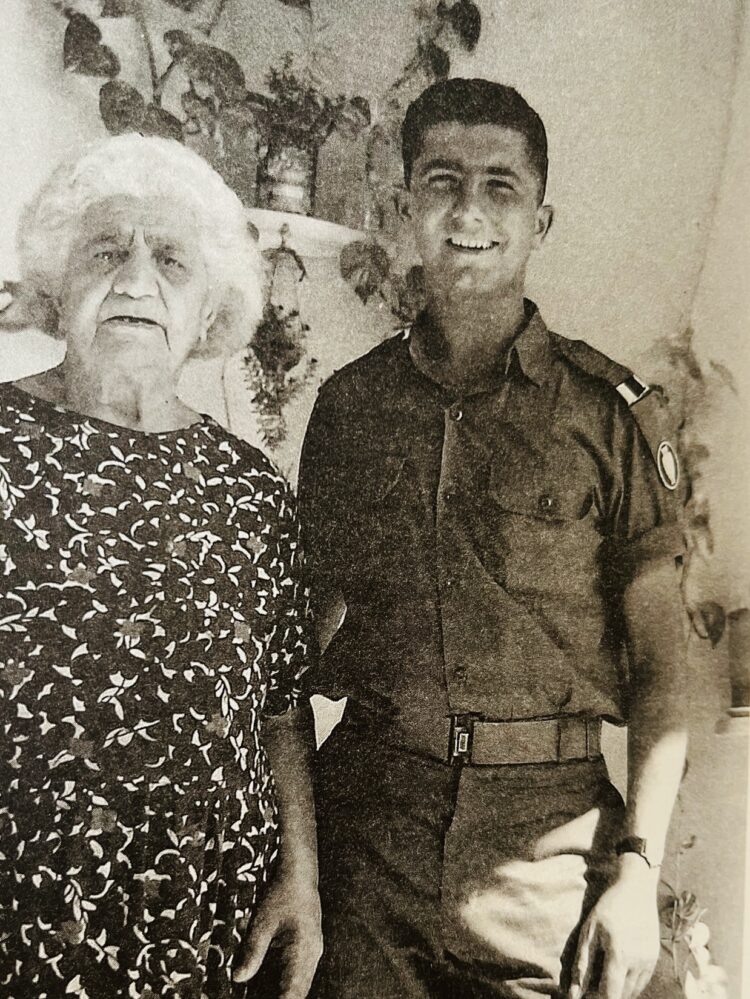

He experienced “a profound feeling of liberation” when his mother sent him to school in London. This segment of his book is the least interesting. From 1964 to 1966, he served in the Israeli army, guarding a stretch of the Jordanian border and working in the signal corps.

To Shlaim, the Israel Defence Force was “decent, ethical and egalitarian, a people’s army.” His service in it marked “the high point” of his identification with Israel. “I believed in the cause, I felt I belonged.”

By the end of his military service, he was a “normal” Israeli, perhaps even a nationalist. “I tended to see things in black and white, viewing Israel as the innocent victim of Arab aggression. I therefore leaned toward a hard line posture in the conflict with the Arabs … I veered to the right of the political spectrum.”

The Six Day War changed his outlook completely. Israel morphed into “a colonial power” and “oppressed” the Palestinians in the occupied areas … “A deeper analysis led me to the conclusion that Israel had been created by a settler colonial movement.” In his jaundiced view, Israel has since become an apartheid state.

He once endorsed a two-state solution, but Israeli settlement expansion in the West Bank killed it off. He now favors a one-state solution between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea with equal rights for all its citizens regardless of ethnicity and religion. One strongly suspects that this, too, is a pipe dream.