The Western-led war against the Taliban in Afghanistan has, we are told, come to an end.

It began on Oct 7, 2001, a month after the 9/11 attacks on New York and Washington, and was initially aimed at degrading Osama bin Laden’s al-Qaeda organization, which had found a home in the country, then ruled largely by the fundamentalist Taliban.

By 2003, the NATO-led International Security Assistance Force included troops from 43 countries, the bulk coming from the United States. At peak levels, the U.S. had 100,000 troops in Afghanistan.

But though bin Laden evaded capture and fled to Pakistan, while the Taliban head, Mullah Omar, was never found, this war would go on for a further 13 years, its aims shifting to the virtually impossible task of defeating a movement that clearly epitomized the ethno-religious beliefs of the majority Pashtun population.

A tribal society, Afghanistan became for NATO a project aimed at creating, among other things, a modern state, with a democratic political culture ensuring equal rights for women and minorities.

This was never going to happen. Afghanistan remained mired in economic and political corruption, run by warlords whose income derived largely from the sale of opium for the international drug trade.

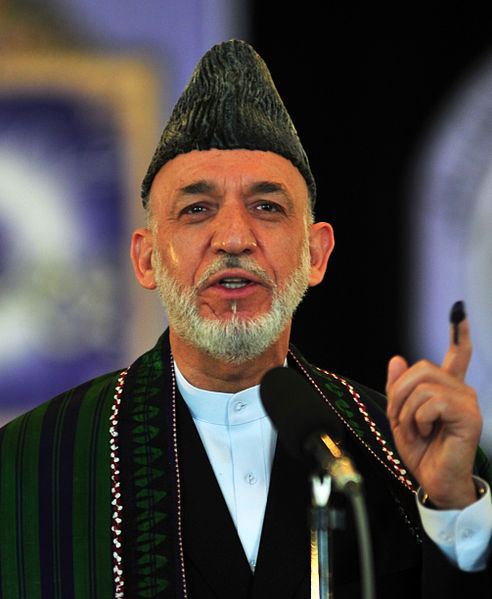

The country’s former president, Hamid Karzai, who won two highly suspect elections in 2004 and 2009, was an unstable politician who spent much of the time biting the American hands that kept him in power.

Once Barack Obama replaced George W. Bush in the White House, it was clear the United States and its allies would try to get out of Afghanistan as soon as they could without losing face.

In May 2014, Washington announced that its combat operations would conclude at the end of the year, leaving just a small residual force at Bagram Air Base and in Kabul until the end of 2016.

On December 28, 2014, the International Security Assistance Force formally ended combat operations in Afghanistan and transferred full security responsibility to the Afghan government at a rather muted ceremony in Kabul.

President Obama issued a statement declaring the step “a milestone for our country,” adding that “the longest war in American history is coming to a responsible conclusion.”

The ceremony was held on the floor of an indoor basketball court, and many people stayed away for fear of the Taliban, which has carried out an unprecedented wave of attacks in the capital while retaking territory abandoned by western troops.

It wasn’t exactly a victory parade, nor will the day be commemorated, the way V-E Day is remembered as the end of the war in Europe in 1945.

By war’s end, 3,387 coalition troops had been killed, including 2,257 American, 453 British, and 158 Canadian, soldiers. Hundreds of thousands of Afghan National Army and Taliban militants had also died, along with countless civilians.

The war has cost America alone over one trillion dollars since 2001. As for Canada, it has cost Ottawa at least $18 billion and perhaps as much as $22 billion.

Operation Enduring Freedom, as the U.S. mission in Afghanistan had been known since 2001, has come to an end. But it will not be enduring, nor did it bring freedom.

A Washington Post-ABC News poll conducted Dec. 11-14 found 56 percent of respondents concluding that it had not been worth fighting.

In the Pashtun heartland in the south and east, many people value the Taliban way of life and moral code. The Taliban made major gains last summer, killing a record number of Afghan policemen and soldiers.

“The Taliban still carries the banner of Islamic morals,” a senior diplomat told the New York Times recently. “The Taliban still grabs people’s minds. And in a fight about who is right, you must gain the minds of the people.”

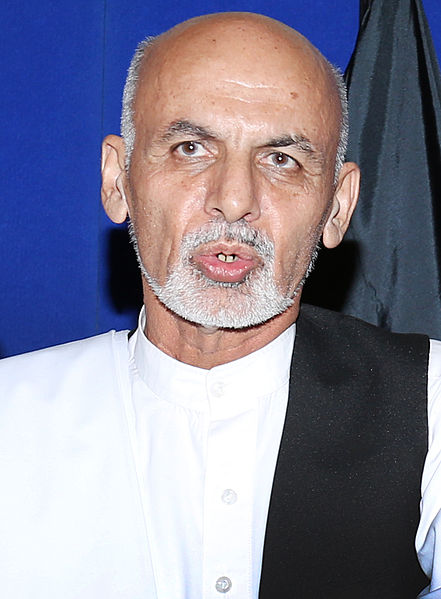

Karzai may be gone but the Kabul government remains corrupt and untrustworthy. Warlords rule much of the countryside. His successor, Ashraf Ghani, the winner in another questionable election last year, is little better.

A State Department poll conducted in late October found that 66 percent of Afghans favor amnesty for Taliban leaders if it paved the way for a peace deal.

So the Taliban is regaining control of much of the country, and the dreams of democracy and modernization have proved to be mirages, unable to transcend the country’s political culture.

Henry Srebrnik is a professor of political science at the University of Prince Edward Island.