As Benjamin (Bibi) Netanyahu observes very early on in his lengthy, intensely interesting autobiography, Bibi: My Story (Simon & Schuster), he owes his political career to his older brother, Yoni, who was killed in 1976 during Israel’s Entebbe raid to free Israeli and foreign airline passengers held hostage by Palestinian and German hijackers in Uganda.

Netanyahu, who greatly admired Yoni as an exemplary role model, was absolutely crushed by his death. “I felt as if my life had ended,” he writes in a candid passage. “I was certain I would never recover.”

Yet Yoni’s “sacrifice and example helped me overcome inconsolable grief, thrust me into a public battle against terrorism, and led me to become Israel’s longest-serving prime minister.”

Yoni’s skepticism concerning the chances of an Israeli rapprochement with its Palestinian and Arab neighbors had a deep and lasting impact on Netanyahu, a veritable hardliner. As he writes, “You can’t build peace on hope alone and you certainly can’t build it on false hope.”

As expected, Netanyahu’s approach to the Arab-Israeli conflict forms an integral component of his book, which runs to more than 700 pages. Yet it is more than just about the push and pull of politics. As it unfolds in chronological order, he deals with his family background, his five-year service in the army, his previous career in business, and his premierships from 1996 to 1999 and from 2009 to 2021.

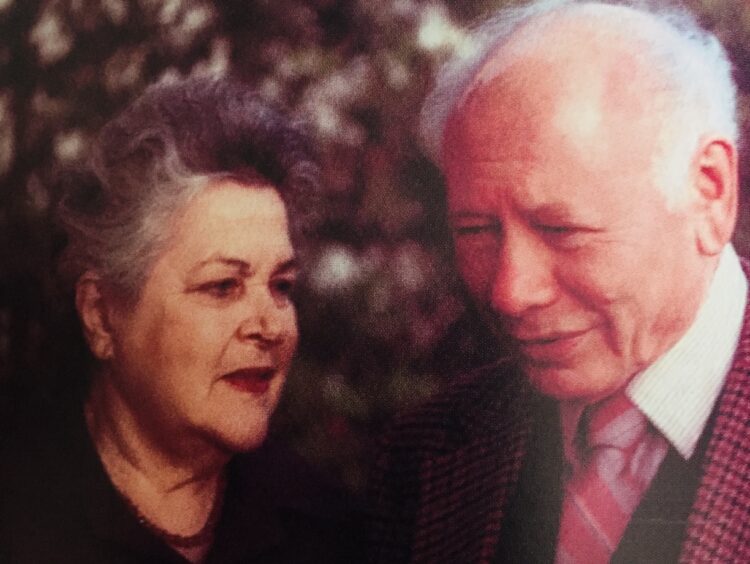

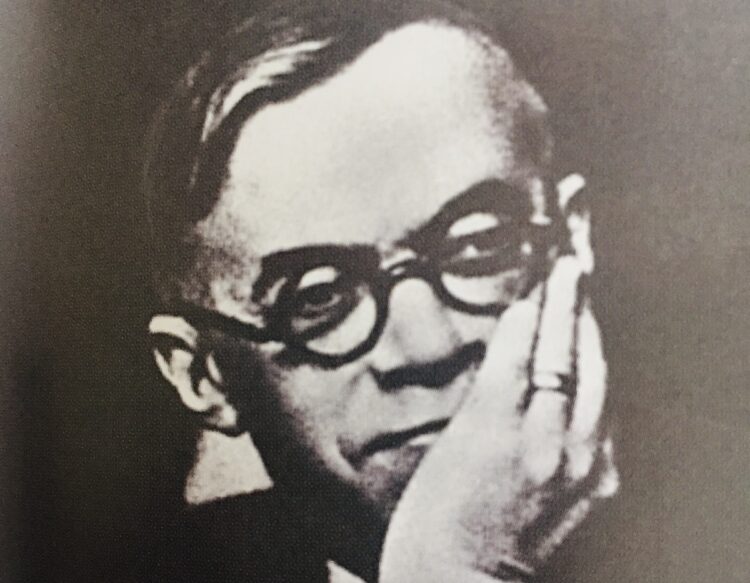

By the Israeli standards of the day, he was born into a well-to-do family. His father, Benzion, a Polish Jew, was a historian and an acolyte of Zionist Revisionist leader Ze’ev Jabotinsky, at whose funeral he was a pallbearer. His mother, Cela, was a person of “inordinate pragmatism and intelligence.”

Netanyahu learned a crucial lesson from his father’s understanding of politics in the United States, Israel’s chief ally. “He was the quintessential practitioner of Jabotinsky’s formula: ‘Influence government through public opinion, influence public opinion by appealing to justice, influence leaders by appealing to interests.'”

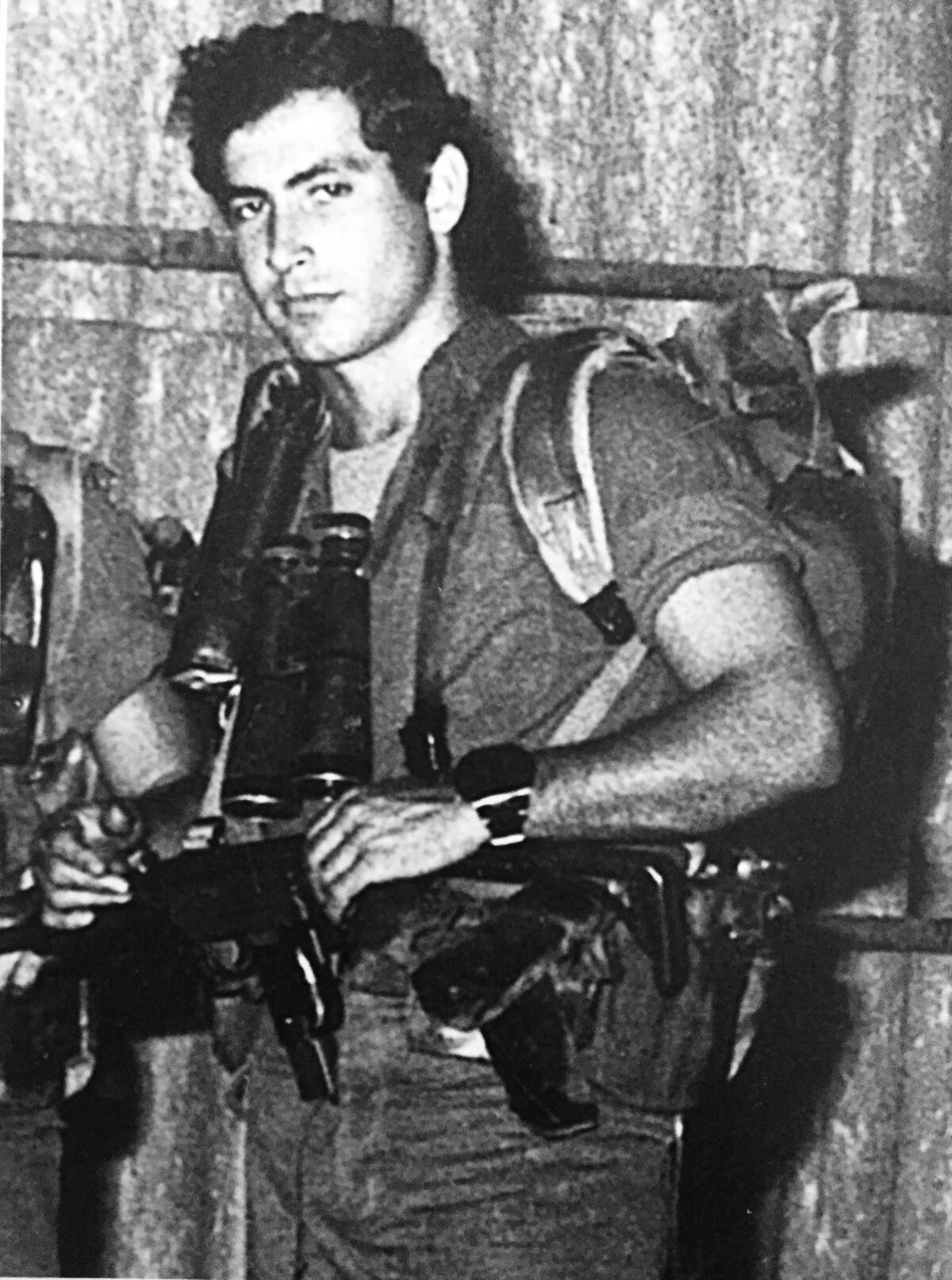

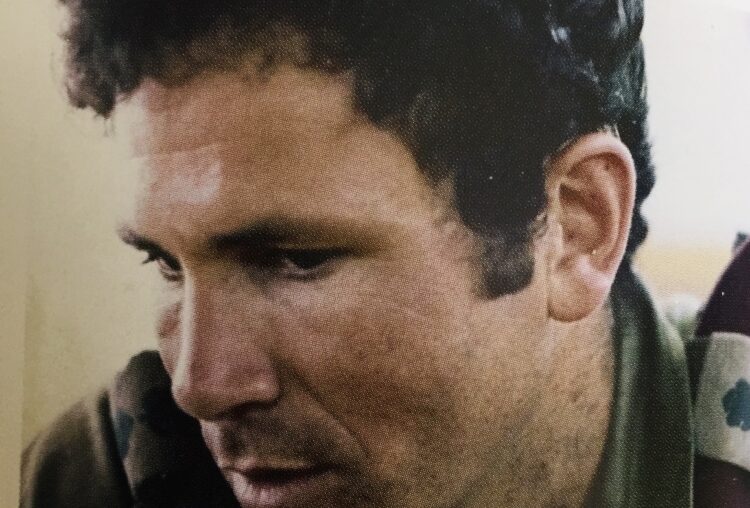

Netanyahu, having attended high school in the United States, enrolled in the army in August 1967, two months after the Six Day War.

A member of the elite Sayeret Matkal special commando force, he participated in raids on Beirut airport and the PLO’s Karameh base in Jordan. During operations in the Suez Canal and the slopes of Mount Hermon on the Golan Heights, he almost drowned and froze. In 1972, he and other commandos stormed a Sabena Airline plane at Lod Airport, near Tel Aviv, that had been commandeered by terrorists.

Due to extended marches in which he carried heavy backpacks, he still suffers from chronic back pain.

After Yoni was killed, he established the Jonathan Institute, which advocated a new way of fighting terrorism in Western public opinion. At his father’s suggestion, he convened international conferences in Jerusalem and Washington and published two books on the proceedings, including Terrorism: How the West Can Win.

During this period, in which he studied architecture and business management at American universities and divorced his first wife, Netanyahu was the marketing director of RIM Industries, which manufactured furniture.

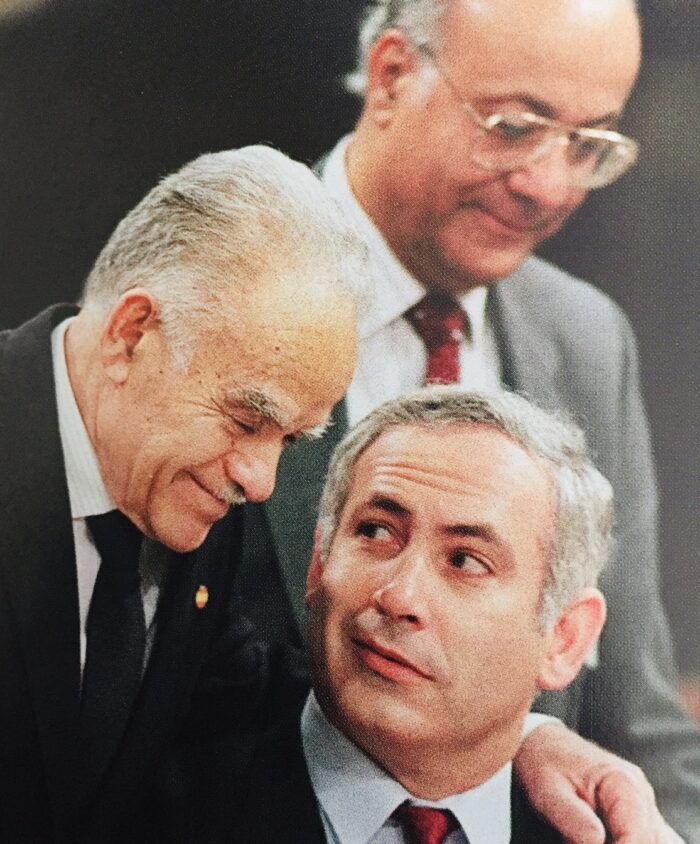

In 1982, Moshe Arens, the chairman of the Knesset’s Defence and Foreign Affairs Committee, his father’s friend and the newly-appointed Israeli ambassador to the United States, offered Netanyahu a job as his deputy. Arens had attended Netanyahu’s conference in Jerusalem and was impressed by his organizational and oratorical skills.

It was in Washington that Netanyahu refined his hawkish views. “The inherent problem in our conflict with the Arabs wasn’t the absence of a Palestinian state, but the presence of a Jewish one,” he says. “The persistent Arab refusal to recognize the right of the Jewish people to a state of their own is what has been driving this conflict from the beginning.”

After Arens’ resignation, Netanyahu stayed on for six months as acting ambassador, where he waged “the battle for public opinion in the U.S.” by giving media interviews and appearing on television talk shows. He thinks his public career was launched during this interregnum.

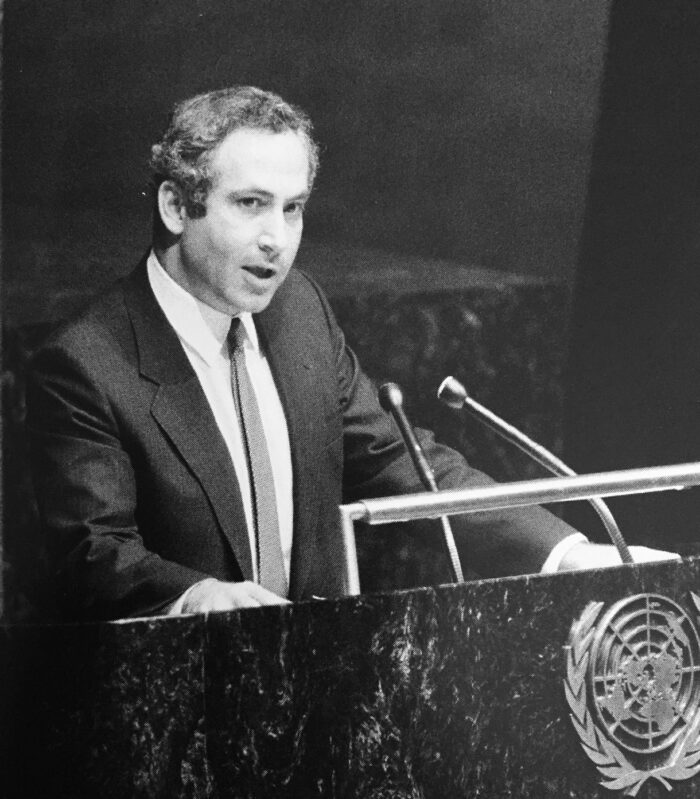

In 1984, the then prime minister, Yitzhak Shamir, appointed him United Nations ambassador, a job that garnered him popularity. Netanyahu returned to Israel four years later to run for the Knesset as a member of the right-wing Likud Party. Arens, having been appointed foreign minister, asked Netanyahu to join his team as his deputy.

He describes his tenure at the UN as “unremarkable.” But during this period, he attended the Madrid peace conference and defended Israel’s policy of non-involvement in the first Gulf War. In one instance, he wore a gas mask as an American reporter interviewed him.

Netanyahu won the leadership of the Likud in 1993, regarding his entry into politics as “a continuation of my family’s legacy.”

Mistrustful of Israel’s Arab enemies, he staunchly opposed Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin’s plan to withdraw from the Golan in exchange for a peace treaty with Syria. “As Yoni had explained, if Israel went down from the (Golan), it would become so vulnerable that it would invite a Syrian attack and the peace would collapse.” He adds, “I believed Israel should retain the high ground of the Golan in any future deal.”

Nor did Netanyahu place any trust in the Palestinians, or its leader, Yasser Arafat. Blasting the 1993 Oslo accords as a Palestinian ruse designed to deceive Israel, he writes, “The unchanging and thinly disguised PLO strategy of destroying Israel in stages completely contradicted Oslo’s ostensible message of peace and reconciliation.”

Netanyahu is convinced that Rabin’s “decision to implant Arafat and the PLO … near Israel’s major population centers was doomed to failure. Instead of bringing peace, it brought terror.” Netanyahu claims that Arafat “personally orchestrated many of the terrorist attacks and suicide bombings” inside Israel.

Nonetheless, Netanyahu regards Rabin as a patriot. “Though we differed on Oslo, we shared many positions, such as the incipient danger of a nuclear Iran and on the need for defensible borders …” Describing Rabin’s assassination as “a tragedy of historic proportions,” he claims it left him with a sense of “horror and grief.”

Although he condemned Oslo as “seriously flawed” and thought it “compromised Israel’s security,” he decided to honor the agreement under two conditions: “Palestinian reciprocity and Israeli security.”

Having ascertained that these conditions could be met in the West Bank town of Hebron, Netanyahu pulled out of 80 percent of it in 1997. In the same year, he ordered the Mossad to assassinate Khalid Mashaal, a top-ranking Hamas official living in Amman. The mission went awry, damaging Israel’s bilateral relations with Jordan. In retrospect, Netanyahu muses, he should have “nixed” it.

Netanyahu established friendly relations with U.S. President Bill Clinton, but their differences over the Palestinian issue was a cause of tension. “I was dealing with a U.S. administration totally in the grip of the Palestinian Centrality Theory, which held that Palestinian grievances were at the heart of the Middle East conflict …” Netanyahu contends that their grievances were really “directed against Israel’s very existence, in any territory.”

“You didn’t need to be a genius to understand that as long as the Palestinians … clung to an ideology hell-bent on destroying Israel, Israeli withdrawals wouldn’t advance peace,” he goes on to say. “The Palestinians were not interested in having a state of their own next to Israel. They were interested in having a state of their own instead of Israel.”

This led to Netanyahu to his self-serving conclusion that the road to a broader peace arrangement between Israel and the Arab world did not go through the Palestinians, but around them. And so the seeds of the 2020 Abraham accords were planted, enabling the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, Morocco and Sudan to normalize ties with Israel.

Netanyahu opposed Prime Minister Ariel Sharon’s unilateral pullout from the Gaza Strip, warning it would result in the formation of a hostile Islamic terrorist base. Unable to bridge the gap in their respective policies, he resigned as finance minister in Sharon’s cabinet. He was sorry to leave. In this post, he boasts, he helped transform Israel’s quasi-socialist economy into a dynamic free market economy that revolutionized Israeli society.

By his reckoning, the Israeli press has been largely hostile to him, “ripping to pieces” his third wife Sara and their eldest son, Yair. The “relentless attacks” on them remain “dagger thrusts to my heart,” he confides.

He considered resigning from politics after the Likud’s lacklustre performance in the 2006 election, when it won only 12 Knesset seats. Sara prevailed upon to stay the course. “Bibi, this is your life,” she told him. “The country needs you.”

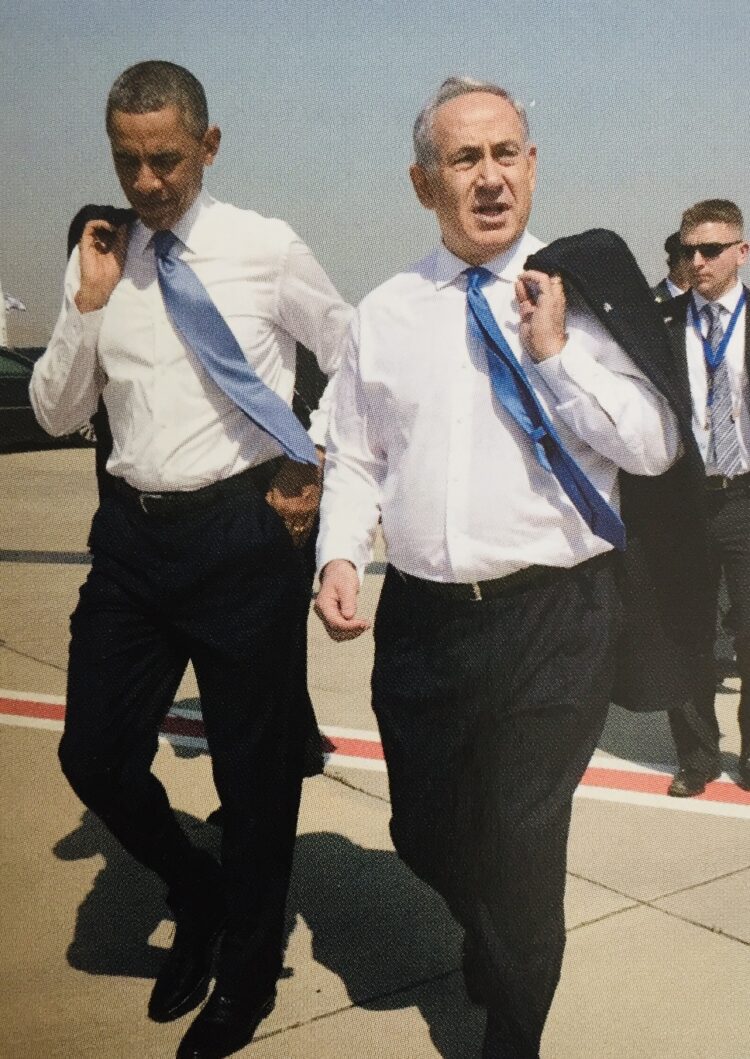

It is no secret that Netanyahu’s relationship with U.S. President Barack Obama was contentious. “For me, the clash with Obama was not personal. It was ideological.”

Obama passionately supported a two-state solution and, in Netanyahu’s view, he “minimized the consequences” for Israel’s security. Obama was also determined to impose a West Bank settlement construction freeze on Israel. Netanyahu believed the Palestinians “should have all the powers required to govern themselves but no power to threaten Israel.” In other words, he was loathe to support Palestinian statehood or agree to a full construction freeze in the West Bank.

“We clearly differed on the Palestinian issue, which Obama viewed through the distorted prism of the Palestinian narrative. He truly believed the Jews of Israel were neocolonials usurping land from native Arab inhabitants … He disregarded our history and disrespected Israel’s elected leader, who dared to disagree with him.”

The 2015 Iran nuclear accord sharpened their differences. “While I genuinely appreciated Obama’s help in maintaining Israel’s qualitative military edge, I could not look aside when he signed the Iran deal.”

Netanyahu was extremely critical of it because it gave Iran the “unlimited right to enrich uranium, kept Iran’s nuclear facilities intact with no effective inspection regime, and enabled Iran to develop ballistic missiles” and destabilize the Middle East through its financial and logistical support of Hezbollah and Hamas.

“I attacked the deal mercilessly, calling it a capitulation and a mistake of historic proportions.”

Four months before it was signed and sealed in Vienna, Netanyahu lambasted it in a blistering speech in the U.S. Congress that annoyed Obama. In his address, he called for the dismantlement of Iran’s military nuclear capabilities and a cessation of its aggressive behavior in the region. “Iran would have to dismantle its centrifuges — which serve the sole purpose of enriching weapons-grade uranium — shut down its underground nuclear bunkers, terminate its weapons development program, and cease its terror campaigns throughout the Middle East and beyond.”

Only a “credible military option” can prevent Iran from becoming a full-fledged nuclear power, he maintains. With this in mind, Netanyahu ordered the air force to gear up for a strike against Iran’s nuclear facilities, a plan of action opposed by the military and by the Mossad and Shin Bet intelligence services.

In summarizing his clash with Obama, he writes, “If he had confronted Iran, recognized our sovereignty in the Golan and Jerusalem, and dealt realistically with the Palestinian issue, I would have praised him to the gills. But since he went in an entirely different direction that could imperil Israel’s future, I was left with no alternative but to confront him and his policies. I never faced a tougher challenge.”

Needless to say, Netanyahu fared better under Donald Trump’s presidency, during which the United States withdrew from the Iran accord, recognized Jerusalem as Israel’s capital, moved its embassy to Jerusalem, recognized Israel’s territorial claim to the Golan, and accepted the legality of Israeli settlements in the West Bank.

Yet even Trump irritated Netanyahu. “He had become convinced that I was the obstacle to a Palestinian-Israeli peace that Mahmoud Abbas (the leader of the Palestinian Authority) was ready for.”

On the whole, he was eminently pleased with Trump, who, he argues, “adopted an entirely new approach to peacemaking.” Complimenting him as a “true trailblazer,” he says, “Despite bumps in the road, our years together were the best ever for the Israeli-American alliance, strengthening security and bringing four historic peace accords to Israel and the Middle East.”

The basic principles that have guided Netanyahu’s attitude to peace with the Palestinians remain in place as he edges closer to resuming the premiership.

The list is headed by two consistent principles, none of which include the possibility of Palestinian statehood: “the Palestinians would recognize Israel as the Jewish state and end all claims against it, and Israel would retain military and security control west of the Jordan River. Israel would not return to the 1967 lines, and no Palestinian refugee would be accepted in the Jewish state. Jerusalem would remain united as Israel’s capital, and the United States would recognize Israel’s sovereignty over all the Jewish communities in Judea and Samaria … Gaza would need to be demilitarized and transferred from Hamas rule to the control of Palestinians committed to peace … Israel would normalize relations with Arab states.”

Currently on trial on charges of fraud, breach of trust and bribery, Netanyahu dismisses these accusations under the broad headings of “character defamation, press calumny and legal harassment.”

As he puts it, “You can criticize me for many things. But there’s one thing those who know me best or have worked closest with me would never accuse me of, and that is being corrupt. From my earliest days, Father told me never to touch money if I ever entered public life. That remained sacrosanct to me.”

In summing up, Netanyahu believes he has lived “a life of purpose” dedicated to securing “the future of my ancient people.” This mission will continue “to inspire me until the end of my days.”

This is how he wishes to be remembered as he struggles to form his next government.