Like Jews, Mennonites are a people of the diaspora. Reclusive, peaceful and pacifist in outlook, they are a Protestant sect that emerged in Dutch and Germanic lands during the Reformation. Scattered throughout dozens of countries, Mennonites outside Germany were often opposed to nationalism and rarely regarded themselves as Germans per se, despite their affinity to the German language.

Yet in Germany, a hefty proportion of Mennonites aligned themselves with the aggressive and militaristic Nazi cause and some believed that Adolf Hitler was a messianic figure worthy of adulation.

The Mennonites’ association with Nazi Germany is minutely traced by Benjamin W. Goosen in Chosen Nation: Mennonites and Germany in a Global Era, published by Princeton University Press. An American Mennonite himself, Goosen explores this little-known topic in methodical fashion.

Mennonites and Jews were considered “historic religious minorities defined by racial ancestry,” he writes. But while Nazi propagandists reviled Jews, they admired Mennonites as pure-blooded Aryans.

Few Mennonites were strong supporters of the Weimar Republic, linking it with Germany’s defeat in World War I. Opponents of Bolshevism, they portrayed their sect as a “racial church” and began joining the Nazi Party well before Hitler took office in 1933.

According to Goosing, “strongly articulated antisemitism did not enter Mennonite discourse until the 1920s.” While antisemitic prejudices were common, some liberals in the Mennonite community felt a kinship to Judaism and equated Jewish freedom with Mennonite freedom.

“Practitioners of both faiths had long experienced social antipathy and state-sponsored violence, as well as occupational, marital and landowning restrictions,” says Goosen.

During World War I, some Mennonite pastors compared violence against Mennonites in Galicia and southern Russia to pogroms directed at Jews.

“It was certainly no accident that Zionism provided a model for Mennonite nationalists. Nevertheless, until the Weimar years, Judaism remained an under-theorized element in Mennonite ideology. Leaders rarely discussed contemporary Jews in their periodicals or mentioned them in their sermons. Although entrepreneurs regularly conducted business with Jews, they did not proselytize.”

As Goosen notes, Mennonites and Jews had a long history of coexistence in Ukraine. “The similarity of Yiddish and German eased daily communication. Business relationships were common. And during pogroms, some Mennonites opened their homes to asylum seekers. Limited intermarriage occurred.” And at least one Mennonite colony in the Soviet Union, Stalindorf, was jointly settled by Mennonites and Jews.

From the 192os onward, anti-Jewish prejudice among Mennonites was greatest in Nazi Party circles. “Insinuations that Jews had killed Jesus, that Jews were ruining the economy, and that they were responsible for Germany’s military defeat in the First World War became common,” he writes.

Mennonite institutions offered no formal opposition to antisemitic legislation in the Third Reich, he goes on to say. And pastors rarely protested when their Jewish neighbors were harassed, beaten or deported.

Mennonite antipathy to Jews was heightened by the perception that “Jewish commissars” in the Soviet Union had been instrumental in the persecution of their brethren. As a result, some Mennonites conflated Bolshevism with Judaism. The Nazis tried to exacerbate such prejudices.

Germany’s Mennonite intelligentsia played a role in producing anti-Soviet literature, which was suffused with antisemitism.

Alfred Rosenberg, the Nazi theoretician, urged Mennonites to purge all “Jewish elements,” such as the Hebrew Bible, from their practice of Christianity. But the majority of Mennonites ignored his recommendation, preferring to worship Jesus in his “historical context.” Goosen quotes one pastor as saying, “Whoever discards the Old Testament also discards Christ.”

Despite this disagreement and the pacifist strain in Mennonite theology, many Mennonite youths voluntarily joined the German army. “Armed service remained tied to national belongings,” says Goosen.

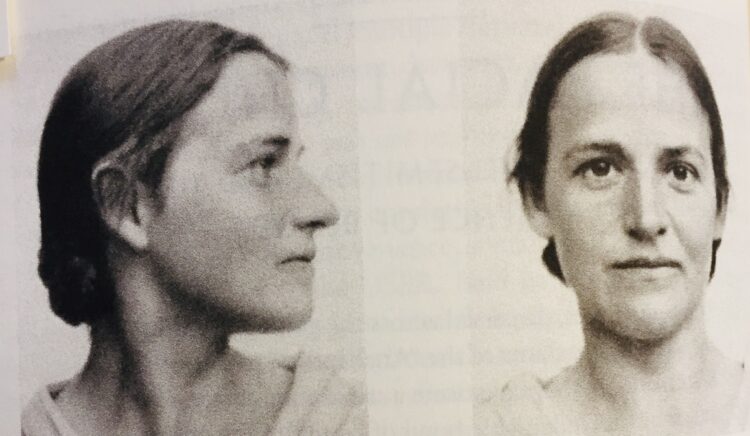

Benjamin Unruh, a Mennonite born in Crimea, was one of the leading pro-Nazi figures in his community. After 1933, he was Nazi Germany’s foremost consultant on Mennonites, and promoted Nazism across Europe and the Americas. A fierce adversary of communism, he envisaged a German protectorate in Ukraine as the fatherland of Mennonites.

Unruh claimed that most ethnically German Mennonites supported Hitler and his regime. “It was not a complete exaggeration,” says Goosen. “Leaders like Unruh knew full well that Ukraine’s Jews were gunned down, often just outside Mennonite villages. They knew that Mennonites received goods taken from murdered Jews.”

Unruh’s ethnocentric beliefs were shared by Fritz Kliewer, a resident of a Mennonite colony in Gran Chaco, Paraguay. Judaism “sickened every upstanding Mennonite,” he insisted.

Kliewer explained that Paraguayan colonists were partial to Old Testament names, such as Sara and Isaac, not out of sympathy for Jews, but for biblical reasons. Yet Mennonite settlers were increasingly giving their children “good Aryan names.”

Among the pro-Nazi Mennonites in Canada were C.F. Klassen, who railed against the “machinations of the Jews,” and J.J. Hildebrand, who promoted the establishment of a fascist Mennonite state in Australia.

Goosen’s examination of Mennonite participation in the Holocaust is revealing. Mennonites were members of the Nazi Einsatzgruppen mobile killing squads in the Soviet Union. Still other Mennonites joined Nazi police forces. One Mennonite, identified as Jakob Reimer, assisted in the suppression of the 1943 Warsaw ghetto uprising and participated in a massacre of Jews in Lublin.

Many Mennonites were expelled from the Soviet Union, and thousands found a refuge in, among other countries, Canada and West Germany. Since then, the ranks of the international Mennonite community have been swollen by non-white recruits from Asian and African nations.

Goosen has written a balanced primer of a pious and insular community whose history, customs and values have yet to be discovered by most people.