Historically, the Middle East has not been a priority for Canadian foreign and defence policy, yet this turbulent region still matters to Canada.

Although Canada, as compared to the United States, plays a relatively minor role there, Canada has been affected by events in the Mideast, from Israel’s struggle with the Palestinians to the West’s armed intervention against the Islamic State organization in Iraq and Syria.

Despite this reality, “scholarship on Canadian foreign and defence policy has neglected the Middle East,” write Thomas Juneau and Bessma Momani in their introductory essay in Middle Power in the Middle East: Canada’s Foreign and Defence Policies in A Changing Region, published by the University of Toronto Press.

Composed of scholarly essays, this useful volume covers the complex gamut of Canada’s interests in an area dominated by several foreign powers apart from the United States — Russia, China, Britain and France.

The essay by Farzan Sabet on the U.S.’ influence on Canadian policy speaks volumes. While Canada usually accedes to American initiatives and interventions, it deviated from that norm when it refused to participate in the 2003 invasion of Iraq, citing the absence of a United Nations mandate.

Canada has “no strong economic and security interests” in the Mideast, nor “a high capacity to exert influence there,” yet it joined U.S. military campaigns in Afghanistan in 2001, Libya in 2011 and Iraq and Syria in 2014.

Although the U.S. is seldom the primary factor shaping Canadian policy, Washington after 2001 pressed Canada to adopt “more forceful measures” on counter-terrorism, intelligence-sharing, border security and customs and immigration regulations.

Canada’s participation in the anti-Islamic State coalition is the subject of an essay by Justine Massie and Marco Munier. “What began as a swift but limited contribution to assist Kurdish forces … under U.S. leadership has evolved into a sizable, long-term, region-wide … aimed at defeating IS.”

While Canada was the first U.S. ally to strike IS in Syria, thereby buttressing its reputation as a steadfast U.S. ally, Canada was the first coalition member to withdraw altogether from combat operations, they add.

As of the spring of last year, 500 Canadian troops were still based in Iraq to train, advise and assist Iraqi forces. The war against IS is expected to become Canada’s second-longest war after Afghanistan.

In another essay, Mike Fleet and Nizar Mohamad examine Canada’s role in training police and security forces in Iraq, Jordan and the Palestinian autonomous areas in the West Bank, which is governed by the Palestinian Authority. “Critics of Canada’s security involvement in the West Bank claim that Canada is complicit in the sub-contracting of Israel’s occupation of Palestinian lands,” they say. This criticism is all the more resonant considering Israel’s expansion of settlements there.

Nermin Allam, in an essay on Canada’s response to the fall of the Muslim Brotherhood regime in Egypt in 2013, writes that Canada maintained a “limited engagement” with President Mohammed Morsi’s Islamic government, and that Prime Minister Stephen Harper described his downfall as a “return to stability.”

With the resignation of Morsi’s predecessor, Hosni Mubarak, Canada expressed its concerns about the future of Egypt’s peace treaty with Israel.

Canada’s foreign minister, John Baird, lauded Morsi’s successor, Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, as a campaigner against terrorism.

Peter Jones, in an essay on Canada’s role as a peacemaker, argues that its involvement has gone through three broad phases since 1945.

The first phase, from the 1950s to the early 2000s, unfolded when Canada portrayed itself as a honest broker and was active in the search for peace. Lester Pearson, Canada’s foreign minister and a future Canadian prime minister, was at the core of these efforts in the wake of the 1956 Sinai war.

During the second phase, from 2006 to 2015, Canada distanced itself from its former position. Jones claims that the groundwork for this phase was laid by Harper’s predecessor, Paul Martin. Harper, in particular, “unstintingly supported Israel.”

In the third phase, during Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s reign, Canada sought to recapture its place as an active player in peacekeeping and conflict resolution.

Canada’s role in Arab-Israel peace processes is dealt with in an essay by Constanza Musu.

As she writes, “Since Canada’s initial participation in the drafting of the 1947 United Nations partition plan to divide the British Mandate of Palestine into a state of Israel and an Arab state, Canada’s official policy on the Arab-Israeli conflict has remained fairly consistent, continuously expressing support for the existence and security of the Israeli state, and the right of self-determination for the Palestinian people.”

Canada’s consistent endorsement of a two-state solution has earned it praise as a “balanced broker,” she says.

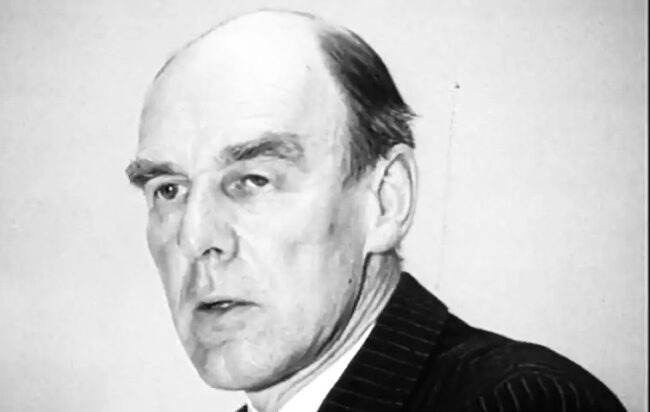

In 1980, Robert Stanfield, a former Conservative party leader, issued a government-commissioned report which stated, “Our strong support for Israel does not mean that we cannot maintain and further develop good relations with the Arab peoples.”

After the publication of the report, Canada opened new embassies in the Arab world and increased trade with it. Canada also continued to object to the construction of Israeli settlements in the occupied territories and Israel’s annexation of East Jerusalem.

Frederic Boily’s essay on Canadian prime ministers and Israel covers Brian Mulroney, Jean Chretien, Paul Martin, Stephen Harper and Justin Trudeau.

Mulroney was staunchly pro-Israel and a fierce opponent of antisemitism. Chretien adopted a middle-of-the-road approach. Martin shifted toward a more favorable view of Israel. Harper justified his pro-Israel stance on moral grounds, particularly during Israel’s war with Hezbollah in 2006. Trudeau, who has rejected the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions movement, is more pro-Israel than Chretien. “To be sure, the Liberals under Trudeau have made obvious efforts to reassure the Jewish community that (it) need not fear a softening of Canada’s support for Israel.”

David Petrasek, in his essay, analyzes Canada’s human rights policy in the Middle East. His conclusion? “Canada has taken a consistent … and firm position … in regard to only two countries in the region — Israel and Iran.”

But in another essay, Jennifer Pedersen says that Canada’s bilateral relations with Saudi Arabia were damaged when it intervened on behalf of two Saudi human rights activists. At the same time, Canada has been a major supplier of military equipment to Saudi Arabia.

These essays, while occasionally plodding, offer valuable insights into Canada’s policy in the Middle East. Middle Power in the Middle East is thus an important work of scholarship.