Seventy five years ago this month, amid the burgeoning Cold War pitting Western capitalist democracies against the communist Soviet Union and its allies, the Hollywood blacklist emerged, upending and ruining the careers of scores of movie directors, producers, actors and screenwriters, many of whom were Jewish.

As Larry Ceplair writes in The Hollywood Motion Picture Blacklist: Seventy Five Years Later (University of Kentucky Press), a thorough examination of this event, it was not a response to trade union activity, which the major movie studios generally opposed, but to a U.S. government “Red Scare,” the third since the end of World War I.

Although most of the blacklistees were or had been members of the Communist Party, which did nothing to support them during their hour of duress, none were accused of spying for the Soviet Union. Nor did evidence surface that they were planning a revolutionary overthrow of the American government.

According to Ceplair, a professor emeritus of history at Santa Monica College and a seasoned observer of the Hollywood film scene, the blacklistees annoyed the powers-that-be due to their efforts to add “realistic” or “progressive” elements to movies they worked on.

In his estimation, the blacklistees all supported a liberal reform agenda (civil rights, civil liberties, protection for immigrants and women’s rights), engaged in labor union organizing, and fought against fascism and antisemitism.

As he points out, they represented but a small proportion of those blacklisted during a ten-year period of conservative cancel culture from the late 1940s onward. Thousands of university professors, government employees and trade unionists suffered the same fate.

The motion picture blacklist era, which paved the way for the McCarthyist hysteria of the 1950s, began when two members of the House of Representatives’ House Committee on Un-American Activities convened at the Biltmore Hotel in Los Angeles in May 1947. The committee itself could only “expose and intimidate,” not sack employees, he says.

Eager to learn about “communist infiltration” of the film industry, the law makers interviewed one studio president, Jack Warner, as well as 14 friendly witnesses from the anti-communist Motion Picture Alliance for the Preservation of American Ideals, whose members included Robert Taylor, Barbara Stanwyck and John Wayne.

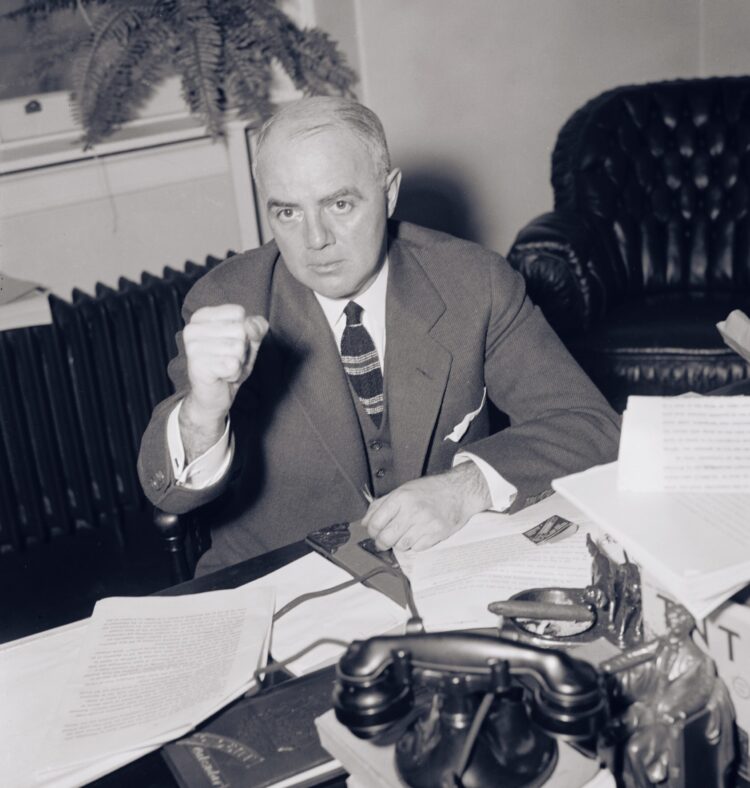

The committee chairman, J. Parnell Thomas (Republican, New Jersey), was dissatisfied with the outcome of the proceedings and subpoenaed a number of “unfriendly” witnesses to appear at hearings set for October of that year.

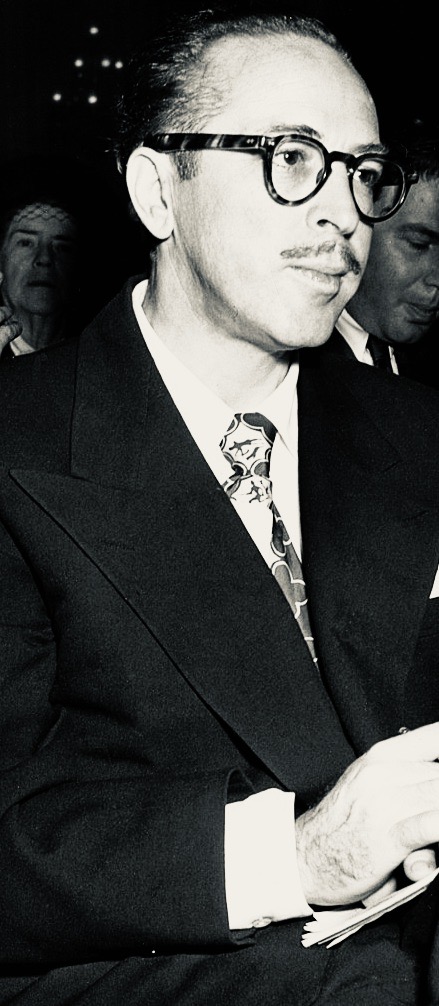

The so-called Hollywood Ten — Alvah Bessie, Herbert Biberman, Lester Cole, Edward Dmytryk, Ring Lardner, Jr., John Howard Lawson, Albert Maltz, Samuel Ornitz, Adrian Scott and Dalton Trumbo — declined to answer questions such as, “Are you now or have you ever been a member of the Communist Party?” Nor were they willing to incriminate colleagues, or “name names,” citing their first amendment rights.

Voted in contempt of Congress, they were sentenced to prison in 1948 for six months to a year. While languishing in jail, Dmytryk decided to cooperate with the committee.

Ceplair says the movie blacklist, keenly supported by anti-communist actors such as Ronald Reagan and Adolphe Menjou, was essentially the work of studio bosses like Louis B. Mayer, Samuel Goldwyn and Harry Cohn. (The television blacklist was compiled by the networks and advertisers).

The majority of the moguls were Jewish, politically conservative and staunchly anti-communist. “They preferred to keep their Jewishness unobserved, but they were not successful,” says Ceplair, mostly referring to Hollywood’s early years. “The wealth they amassed did not gain them entry into high society. They were excluded from the best country clubs and private schools, and they were regularly attacked by a variety of groups as money grubbers, sexual immoralists and ‘dirty Jews.'”

The blacklist became operational in November 1947 after the studios fired five of the Hollywood Ten and promised not to rehire them until they had recanted and purged themselves of their communist taint.

By Ceplair’s estimate, some 300 people were affected by the blacklist, which prevented them from earning a living.

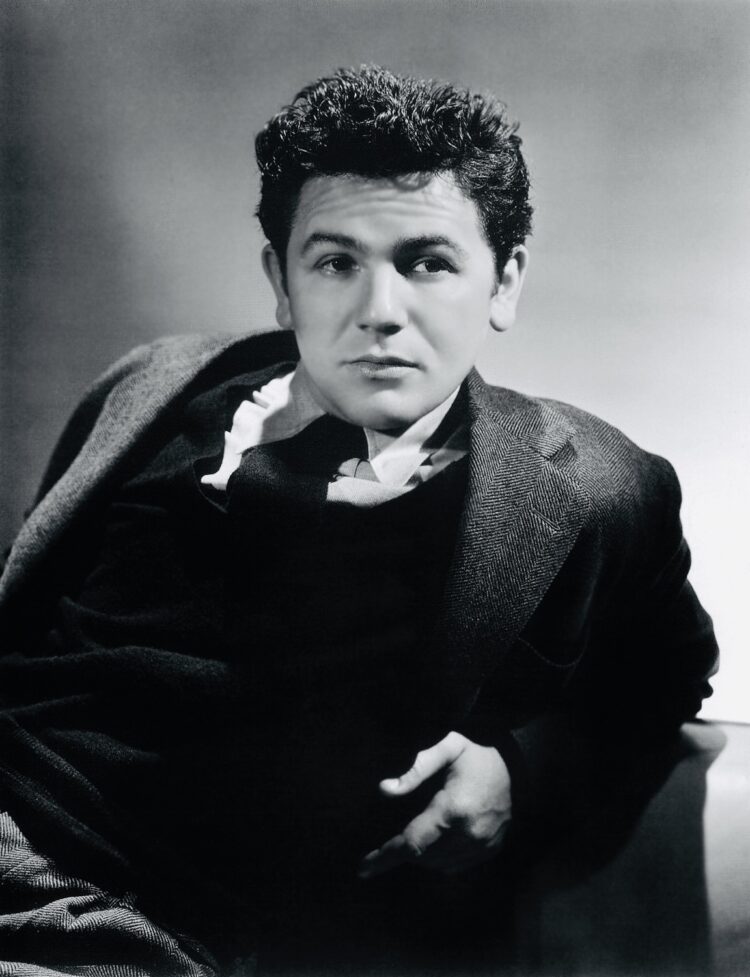

During this period, which coincided with the execution of convicted Soviet spies Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, paranoia and fear gripped the entertainment industry. The blacklist shattered careers and destroyed friendships and lives. In 1952, the Jewish actor John Garfield died of a heart attack at the age of 39, reportedly brought on by the stress of having to prove he was not a communist or a communist pawn.

Philip Loeb, who appeared in The Goldbergs, committed suicide in 1955. Jules Dassin, the director of Brute Force and The Naked City, fled to Italy as an “undesirable” alien.

This studios’ policy of self-regulation, outlined in the so-called Waldorf Declaration, stated, “We will not knowingly employ communists or a member of any party or group which advocates the overthrow of the government of the United States by force or by illegal or unconstitutional methods.”

There was no “list”per se, he notes, saying that studio executives based their hiring or firing decisions on the transcripts of the House Committee on Un-American Activities. “No production company ever admitted to having utilized a blacklist,” he says.

Yet in order to remove themselves from it, a blacklistee had to appear before the committee, apologize for joining the Communist Party, laud the committee, and name names, Ceplair adds.

Against the backdrop of the blacklist, Hollywood churned out almost 50 anti-communist movies and ceased making “social problem” movies. Variety, in the summer of 1948, reported that studios “are continuing to drop plans for ‘message’ pictures like hot coals.”

In Ceplair’s view, the studios’ decision to produce such propagandistic films was induced neither by patriotic duty nor by ideological convictions, but by fear of the long-term consequences of not abiding by the government’s Cold War considerations.

The blacklist lasted until 1960 and only ended when the studios concluded that the open hiring of blacklisted personnel would not have an adverse impact on box office receipts. “The producers’ associations never stated that the blacklist had ended because they had consistently maintained that there had never been a blacklist in the first place.”

Many of the blacklistees, like Dalton Trumbo, the screenwriter of Exodus, were eventually rehired. But a significant number found it difficult to regain their footing in the industry.

In Ceplair’s judgment, the blacklist neither strengthened the United States’ national security nor improved the quality of films. “It was probably a very small factor in the decline of the studio system, which had been much more strongly impacted by the rise of television.”

The blacklist, in short, was a stain on the fabric of American democracy.