Ada Ushpiz’s biopic, Vita Activa: The Spirit of Hannah Arendt, takes a sweeping look at the life and ideas of a controversial philosopher. Scheduled to be screened at the Bloor Hot Docs Cinema in Toronto from June 10-16, this thoughtful two-hour film portrays Arendt as an independent thinker who was neither a classic liberal nor a typical conservative.

Born into an assimilated Jewish family in Germany in 1906, she wrote two books which still resonate — The Origins of Totalitarianism and Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil, both of which form the backbone of the film.

Ushpiz, an Israeli, examines Arendt through the lens of her close relationships with German academics Martin Heidegger and Karl Jaspers, her reporting of the Eichmann trial for the New Yorker magazine and her attitude toward Zionism and Jewish statehood.

Rigorously intellectual in tone and substance, this documentary is composed of several moving parts: reminiscences of Arendt by colleagues and observers, commentaries by academics, segments from an extended interview with Arendt carried by a West German TV channel in 1964, and file footage from pre and post-war Germany and the Holocaust.

Ushpiz’s admiration of Arendt shines through, but her film is reasonably balanced.

As a child, Arendt was curious and opinionated, a voracious reader of books who soaked up knowledge effortlessly. These characteristics would define her as an adult.

At university, she studied under Heidegger, a married man with whom she had a love affair. Heidegger joined the Nazi movement, but after the war, Arendt renewed her bond with him and promoted his works. Beyond saying he had been “foolish” and a “potential murderer,” she essentially let him off the hook.

Arendt, whose biological father died when she was very young, finished her PhD under the guidance of Karl Jaspers, who’s described as her surrogate father.

She left Germany in 1933, the year the Nazis assumed power, and went to France. Arendt was a German by culture, language and philosophy, but not by history. As she put it in a letter to Jaspers: “I know only too well how late and how fragmentary the Jews’ participation in that [German] destiny has been …”

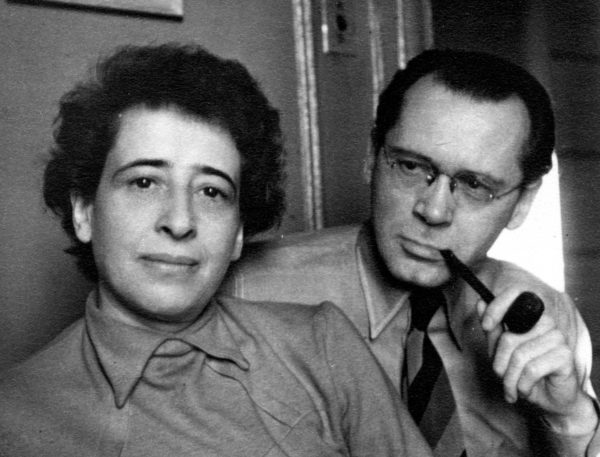

After being interned in the Gurs camp, she fled to the United States, accompanied by her second husband, the German Marxist Heinrich Blucher.

The film dwells at some length on The Origins of Totalitarianism, which examined the roots of Stalinism and Nazism, but in the main, it focuses on Eichmann’s trial and Arendt’s reaction to it.

Eichmann, one of the chief facilitators of the Holocaust, claimed he was not an antisemite and had no blood on his hands. It was an absurd claim, of course, but Arendt bought a chunk of it.

Yet she was extremely critical of the Jewish Councils that administered the Nazi ghettos. In her jaundiced view, Jewish elders cooperated with the Germans and let themselves be used as “instruments of murder.”

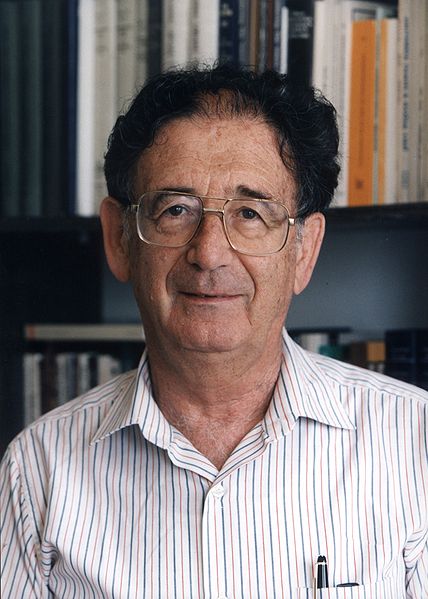

The Israeli historian Yehuda Bauer challenges Arendt’s thesis. Jews did not cooperate, he asserts. They yielded to Nazi authority. Aharon Applefeld, the Israeli novelist and Holocaust survivor, accuses her of having lacked empathy for the impossible situation captive Jews found themselves. Still others think she was a self-hating Jew who basically exonerated Eichmann of his crimes.

Arendt, though a Zionist during the war, had a problem with ethnic nationalism, claiming that a Jewish national home in Palestine opposed by Palestinian Arabs would not really be a true home. Eventually, Arendt likened Zionism to racism and chauvinism and compared it to master race theory.

As the film suggests, Arendt was an iconoclast who marched to her own music.