There has always been a small minority of Jews who regarded Judaism as a burden to be jettisoned. Such Jews usually resolved their problem by means of complete assimilation. This invariably meant conversion to another religion, marriage to a spouse of a different faith or flight into exclusively non-Jewish circles.

Over the centuries, this pattern has manifested itself in the Christian world, particularly in pre-Inquisition Spain and in Europe from the 18th century onward.

Todd M. Endelman, an American scholar, examines this phenomenon in Leaving the Fold: Conversion and Radical Assimilation in Modern Jewish History, published by Princeton University Press. It’s a superb work of scholarship, covering major European countries and touching on the United States and Canada. He excludes Muslim countries from his inquiry.

As he observes early in his book, assimilation was not really an option for a Jew in the pre-modern era, when Jews constituted a distinct collective unit and differed from their Christian neighbors in terms of religion, ethnicity, social and cultural habits, legal status and employment. But with the onset of Jewish emancipation, a process touched off by the French Revolution, Jews moved from exclusion to inclusion and from the periphery to the mainstream.

Yet, as Endelman points out, assimilated Jews did not necessarily erase the stigma of their Jewishness, or achieve unconditional social acceptance, after abandoning Judaism. “The perception that Jews were different in kind from non-Jews was too well entrenched, too rooted in Western culture and thought, to disappear.”

In the best of circumstances, especially in liberal states like Britain, France and the United States, Jews still faced discrimination, stigmatization, legal disabilities, verbal abuse and even physical violence. Antisemites were determined to reverse integration and revoke emancipation, as the French army officer Alfred Dreyfus learned to his horror in the 1890s.

Radical assimilation was invariably the objective of Jews who were alienated from Jewish communal life. Some, like the Russian Jew Jacob Brafman, the author of The Book of the Kahal (1869), an anti-Jewish tract, were simply self-hating Jews.

Still others, like the German poet Heinrich Heine, considered baptism as a prerequisite for an unhindered public career. “The baptismal certificate is the ticket to admission to European culture,” he wrote.

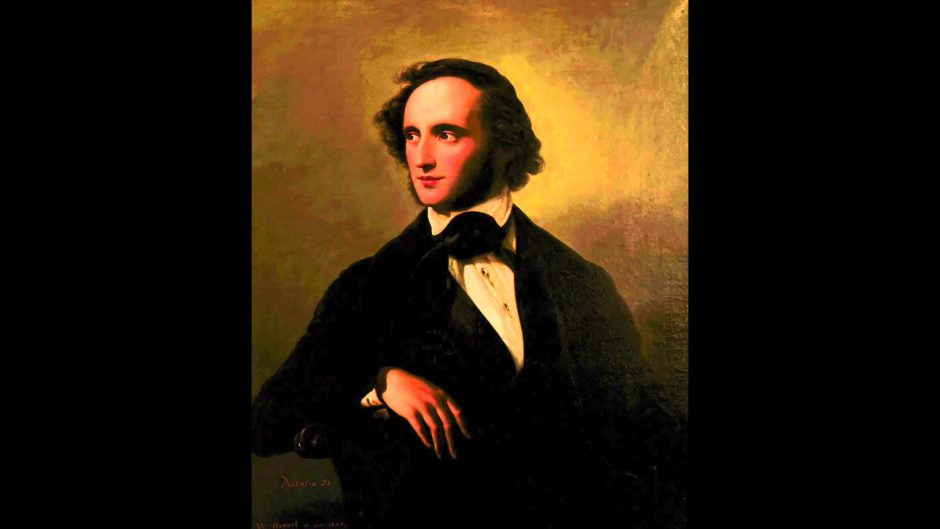

With this in mind, the fathers of Benjamin Disraeli, the 19th century British prime minister, and of Felix Mendelssohn, the German composer, converted to Christianity so that they and their children might have a better chance of achieving success in their respective fields of endeavor.

British converts like the historian and antiquarian Sir Francis Palgrave (1788-1861) switched course in mid-life. The son of Meyer Cohen, a wealthy London stockbroker, he converted to Christianity, and changed his surname, before his marriage in a Church of England ceremony.

Long before a Rothschild became the first professing Jew to sit in Britain’s House of Commons, converted Jews such as Sir Manasseh Masseh Lopes (1788-1854), David Ricardo (1772-1823) and Sir Ralph Franco Lopes (1788-1854) already had taken their places in Parliament. And, as Endelman notes, two pillars of British society, David Cameron, the current prime minister, and Boris Johnson, the former mayor of London, are descended from Jews.

Before the 19th century in Central Europe, Endelman notes, most Jewish converts were from the lower social strata, the flotsom and jetsam of the Jewish world. But from the 18th century onward, converts tended to be educated, wealthy and worldly. Court Jews like Daniel Itzig (1723-1799) opted out of Judaism and his descendants fully identified as Christians.

As Itzig’s conversion demonstrated, radical assimilation was notably pronounced among a considerable proportion of well-to-do Jews in the German states. By Endelman’s estimate, half of the Jews in Berlin had adopted Christianity by the 1820s. German Jews who remained loyal to their faith encountered great difficulties in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. In academia, the army and civil service, unbaptized Jews had little or no chance of advancement.

Endelman cites Walther Rathenau, the industrialist who served as Germany’s first Jewish foreign minister, as an example of a Jew who never formally severed his ties with Judaism but who was basically ashamed of his origins.

The first modern converts were the conversos of Spain and Portugal, where forced conversions were commonplace. Such conversions also occurred in czarist Russia, where underage Jewish boys were inducted into the Russian armed forces after 1827. From then until 1840, he says, 38.5 percent of the 15,050 Jews conscripted into cantonist battalions converted to the Russian Orthodox religion. Conversion, however, was not limited to that sector of society. The family of Russian Jewish pianist and composer Anton Rubinstein (1829-1894) converted to Christianity two years after his birth.

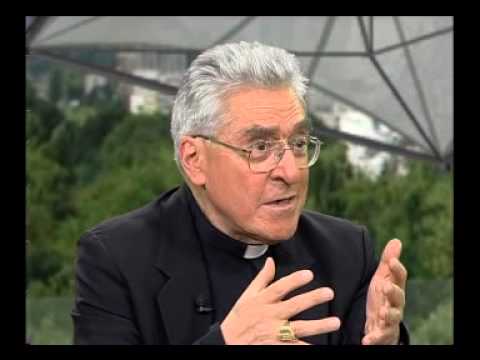

In the 20th century, Jews continued to drift away from their Jewish moorings. Marcel Proust, the French novelist, was the baptized son of a Jewish mother and a Catholic father. Marcel Bloch (1892-1986), the French aircraft manufacturer whose Mirage jets gave Israel an edge in the Six Day War, converted to Christianity in the late 1950s. Religious conviction prompted the Polish-born Jew and Holocaust survivor Aaron Lustiger (1926-2007) to convert and change his first name to Jean-Marie. He became a Roman Catholic priest, an archbishop and a cardinal.

Joseph Korbel, a Czech diplomat, renounced Judaism in favor of Roman Catholicism. “To be a Jew is to be constantly threatened by some kind of danger,” Korbel’s wife said. Their daughter, Madeleine Albright, a U.S. secretary of state, did not discover her Jewish origins until late into adulthood.

Social patterns in the United States led to an upsurge of mixed marriages. The maternal grandmother of the novelist Mary McCarthy, Augusta Morgenstern, was Jewish.

U.S. senator and presidential aspirant Barry Goldwater was the descendant of the Arizona merchant Michael Goldwater (1821-1903), who married a Christian woman. The paternal grandfather of C. Douglas Dillon (1909-2003) — the U.S. secretary of the treasury in the 1960s and a major figure on Wall Street — was a Polish Jew named Sam Lapowski.

In Eldeman’s judgment, radical assimilation, whatever form it took, was neither “an unambiguous success nor failure,” at least before Nazi doctrine erased the difference between baptized and unbaptized Jews. As a rule, conversion was more successful in liberal countries. “In societies where Jew-consciousness was acute, radical assimilation worked patchily.”

He adds, “Radical assimilation worked best, providing both immediate and long-term gains, in societies where it was less in demand, that is, in societies where Jews were less likely to cut their ties to Judaism for strategic reasons.”

It often took several generations for a conversion to take effect, he says, citing the cases of Paul Julius Reuter (1816-1899), the founder of the news agency, and of Gustav Wilhelm Wolff (1834-1913, the patriarch of the Irish shipbuilding firm which built the ill-fated Titanic.

When assimilation was completely successful, even the grandchildren and great-grandchildren of the convert were ignorant of their Jewish past. “The most successful cases of radical assimilation often remain hidden from the historian’s view,” he says.

In Germany, many descendants of intermarried or converted Jews only discovered their Jewish ancestry after the Nazis assumed power in 1933. But some German families with distant Jewish ancestors were left untouched by the Nazis, proving that radical assimilation was achievable even under the worst of circumstances.