Randol (Randy) Schoenberg’s obsessive quest to plumb the depths of his family’s history led him and his son on a journey of discovery in Europe. Their eye-opening trip is the subject of Matthew Mishory’s absorbing documentary, Fioretta, which will be screened in its world premiere at the Woodstock Film Festival on September 30.

Shortly afterward, there will be another screening at the Museum of the Jewish People in Tel Aviv. And in December, the film will be released on a limited basis in Los Angeles.

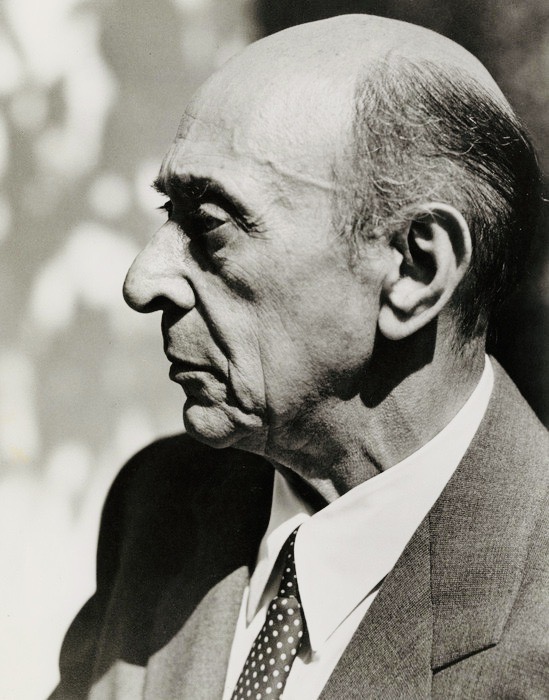

Schoenberg, a lawyer and genealogist who lives in Los Angeles, is the grandson of the late Austrian-American composer Arnold Schoenberg (1874-1951).

Eighteen years ago, on behalf of Austrian Holocaust survivor Maria Altmann, he successfully sued Austria and recovered five paintings by Gustav Klimt the Nazis had stolen from her family in Vienna. The case spawned the Hollywood movie Woman in Gold, starring Helen Mirren and Ryan Reynolds.

From 2005 to 2015, Schoenberg was president of the Holocaust Museum L.A., during which time its new building was constructed. In 2013, he served as its acting executive director.

In Fioretta, he and his 18-year-old son, Joey, try to piece together the fragments of the Schoenberg lineage in Austria, the Czech Republic and Italy. In particular, Schoenberg, a dogged investigator, attempts to find the gravestone of Fioretta, his oldest known ancestor, who died in the 1600s in the Jewish ghetto in Venice.

Schoenberg acknowledges he’s a fanatical genealogist. He’s been at it since the age of eight, when he compiled a family tree. In 1991, he travelled to Prague to learn more about the Schoenberg clan. This aspect of his fascination with genealogy unfolds in questionable reenactments in which an actor portrays the younger Schoenberg. To the film’s detriment, they are rather theatrical and unnecessary.

“I’ve always been interested in memory and in the continuum of history,” he says. Genealogy has enabled him to enter new worlds and reunite his far-flung family, he adds.

Joey, his travelling companion, appears only faintly interested in his father’s avocation. But as they traverse Europe by train, plane and van, Joey perks up and expresses an appreciation of the work his father is doing to excavate some 500 years of family history.

Before embarking on their seemingly once-in-a-lifetime odyssey, they discuss it in their home in Malibu, a modern house that overlooks the Pacific Ocean. Schoenberg’s wife, Pam, and their daughter encourage them to go through with their plan.

Schoenberg is moved to be in Vienna, to which he feels a special attachment. This is where his ancestors lived for hundreds of years before being driven out by the Nazis following Germany’s annexation of Austria in 1938.

He pauses at the Arnold Schoenberg Center, which preserves the legacy of his famous grandfather and on whose board he serves.

They visit a synagogue in central Vienna, where some of his ancestors were married over the centuries. As it happens, it was the only Viennese shul not to be destroyed by the Nazis during the Kristallnacht pogrom in 1938. Its beauty is a reminder of the splendor of Vienna’s pre-Holocaust Jewish community.

After Joey arrives in Vienna, they attend a concert of Schoenberg’s modern music and visit the Arnold Schoenberg Center. They then stop at a cemetery where a number of their ancestors rest in peace.

In Prague, they pay visits to the Altneuschul, one of the world’s oldest synagogues; the Czech National Archives, where they’re shown documents relating to their ancestors, and the old Jewish cemetery, where the novelist Franz Kafka is buried.

At the Jewish Museum archive, they learn that their ancestors were the victims of antisemitism. Expelled from Prague in 1745, they returned three years later.

Back in Vienna, at its archive, they’re told that one of their ancestors, a physician from Bohemia, was one of the first Jews in their family allowed to settle in the city.

In Florence, they gaze at a centuries-old parchment in which an ancestor’s name is mentioned. And in a Jewish cemetery in Venice, they stumble upon Fioretta’s weathered headstone, whose inscription in Hebrew has been ravaged by the elements.

Schoenberg is pleased by their discoveries. Joey is satisfied, too. “It was definitely a bonding trip,” he says.

Mission accomplished.