The first day of 2022 in Israel had an awfully familiar ring to it.

During the early hours of January 1, two rockets were fired at Israel from the Gaza Strip. One exploded in the Mediterranean Sea off the coast of Jaffa. The second landed in the water near Palmachim, south of Rishon Lezion.

Israeli fighter jets, helicopters and tanks launched retaliatory strikes, hitting a variety of targets in Gaza, which Hamas has ruled since 2006.

Islamic Jihad was blamed for the launches, but Hamas said they were triggered by stormy weather, a claim Israeli Prime Minister Naftali Bennett brusquely dismissed. “Whoever aims rockets at the State of Israel must take responsibility,” he said, justifying Israel’s prompt response.

The tit-for-tat exchange occurred seven months after the last war in Gaza, which Israel occupied from 1967 until 2005. The sudden flareup underscored the volatility and unpredictability of Israel’s perennial conflict with Hamas and its sister organization, Islamic Jihad, both of which are supported by Iran.

These Islamic groups do not pose an existential threat to Israel, the preeminent military power in the Middle East. But they are definitely a thorn in Israel’s side, as four cross-border wars since 2008 graphically illustrate.

Israel pulled out of Gaza on the basis of two assumptions, both of which proved to be incorrect. The then Israeli prime minister, Ariel Sharon, believed that calm would prevail after Israel’s withdrawal and that Gaza would continue to be governed by the mainstream Palestinian Authority, which emerged after the 1993 Oslo peace process.

Within a year of Israel’s departure, Hamas decisively defeated Fatah in a legislative election. And in 2007, Hamas staged a bloody coup, ousting Fatah, an important cog in the machinery of the Palestinian Authority.

In rapid succession, Israel and Egypt imposed a land, sea and air blockade on Gaza.

Instead of focusing on building prosperity for its two million inhabitants, many of whom are the descendants of refugees from the 1948 Arab-Israeli war, Hamas armed itself to the teeth to confront Israel, whose existence it categorically rejects.

Since 2001, Hamas has harassed Israel by various means — attempted infiltrations, thousands of rocket and incendiary balloon launches, and countless border demonstrations. These provocations triggered skirmishes and caused wars in 2008, 2012, 2014 and 2021, all of which devastated Gaza and threw it deeper into economic despair.

Since the last round of hostilities last May, which lasted 11 days, Egypt has been trying to broker a durable ceasefire, which could be of mutual benefit to Israel and Hamas. The maintenance of calm along the border would most certainly be in Israel’s interest, but it would also enable Hamas to rebuild Gaza with international funding and improve the lives of its residents.

A lasting truce has yet to be achieved for a number of reasons.

Israel has conditioned full reconstruction in Gaza on the return of the remains of two Israeli soldiers killed in 2014 and of two Israeli civilians who accidentally wandered into Gaza. In exchange for these humanitarian gestures, Hamas insists on the release of a large number of Palestinians held in Israeli prisons, a demand Israel rejects.

Hamas is also demanding development projects and the construction of a port, but these issues cannot be resolved until the others have been settled.

The Israeli government, in an effort to create favorable conditions for truce negotiations, has expanded Gaza’s fishing zone and granted permits to 5,000 Palestinian merchants to enter Israel.

Qatar — an Arab state which does not officially recognize Israel — has thrown Gaza a lifeline, having provided it with a monthly grant of $30 million in cash to alleviate hardships.

By the terms of an agreement reached by Israel, Qatar and Egypt following the last war, the United Nations has been charged with distributing a proportion of these funds directly to 95,0000 needy Palestinian families. Previously, Hamas carried out this task.

Qatari funds have has also been used to buy fuel for Gaza’s only power plant and to pay the salaries of Hamas government employees.

Hamas has an independent source of revenue, collecting as much as $30 million per month from taxes levied on fuel and tobacco exported into Gaza via the Rafah border crossing.

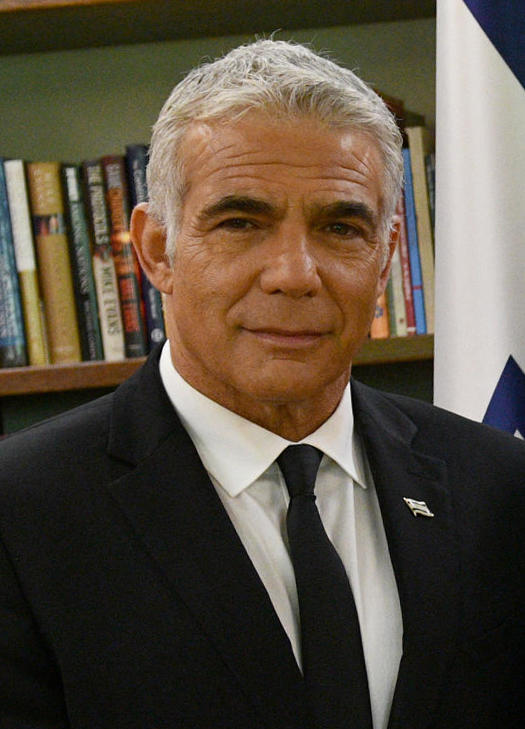

Last September, Israeli Foreign Minister Yair Lapid presented a “new vision” for Israel’s relations with Gaza, but it is highly doubtful whether it will be acceptable to Hamas.

Lapid’s plan is composed of two elements.

During the first stage, Gaza’s crumbling infrastructure would be rehabilitated. During the second phase, an artificial island, serving as a port, would be built off Gaza’s coast.

In return, Hamas would cease aggressive actions against Israel.

“This is not a proposal for negotiations with Hamas,” Lapid said. “Israel will not award prizes to a terrorist organization and weaken the Palestinian Authority that works with us on a regular basis.”

Under his proposal, the Palestinian Authority would assume responsibility for civil and economic affairs in Gaza, but it’s a non-starter because Hamas will never allow itself to be supplanted by its rival.

Israeli politicians have advocated similar plans in the past, but none have come to fruition because most Palestinians seek a political solution in the form of a two-state solution. The current Israeli government, like the one before it, is not even remotely interested in this approach.

Proceeding from the assumption that its perennial conflict with the Hamas regime can only be managed rather than resolved, Israel has built a $1.1 billion 10-meter-high concrete and iron wall along and under the length of its 65-kilometer border with Gaza.

Finished last month after three years of construction, the barrier is fitted with sensors and designed to end the threat from Palestinian attack tunnels. “It denies Hamas one of the capabilities that it tried to develop,” Israel Minister of Defence Benny Gantz said on December 7.

“The barrier is reality-changing,” noted Israel’s chief of staff, General Aviv Kohavi. “What happened in the past won’t happen again.”

Hamas built its first tunnels in 2004 to conduct attacks against Israel. In 2006, Palestinians used this method to kill three Israeli soldiers and kidnap a fourth, Gilad Shalit, who spent five years in captivity before being released in a prisoner swap.

During the 2014 war, Palestinian fighters made extensive use of tunnels, but many were subsequently destroyed by Israel. Cross-border tunnels played virtually no role in last May’s war, but Israel decided to play it safe and finish the barrier.