Otto Preminger’s filmography is well known to cineastes. In a career spanning continents and decades, he directed movies ranging from Laura and Anatomy of a Murder to Exodus and Advise and Consent. Some were extraordinarily good. Still others, such as Skidoo and Tell Me That You Love Me, Junie Moon, were rubbish.

Born in Poland and raised in Austria, he is often remembered today not for his eclectic body of work but for his temper tantrums. “Otto was a tyrant and a bully who could be cruel,” writes Foster Hirsch in the paperback edition of Otto Preminger: The Man Who Would Be King, published by the University of Kentucky Press. Yet Preminger could be charming. “The fact of the matter is this,” he goes on to say. “Otto Preminger was a major filmmaker who was a flawed human being.”

Brilliant and impatient, he was a canny showman, a high-class huckster, and an artist with high principles, says Foster — a professor of film at Brooklyn College — in succinctly summing him up in this wide-ranging and erudite book.

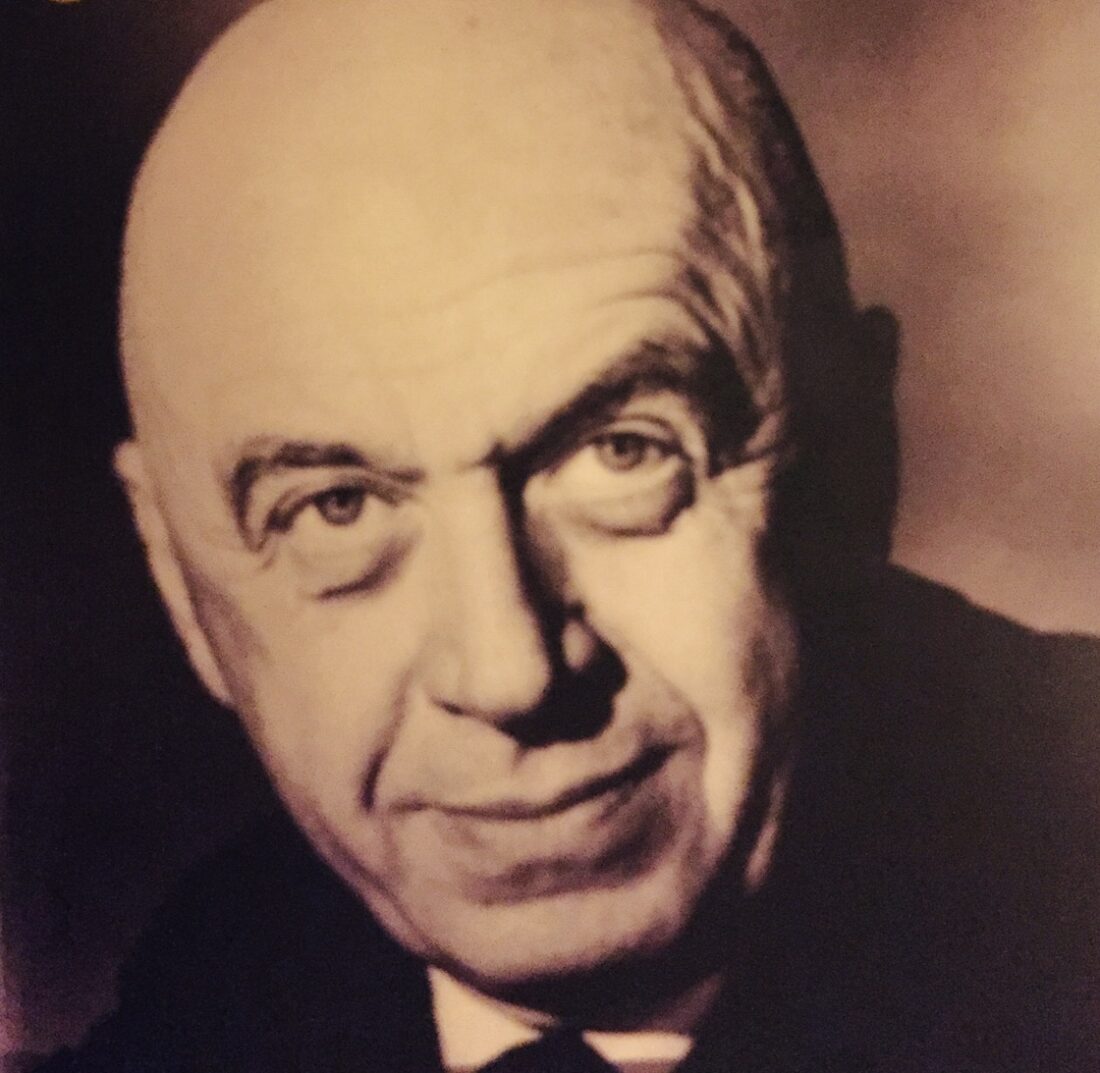

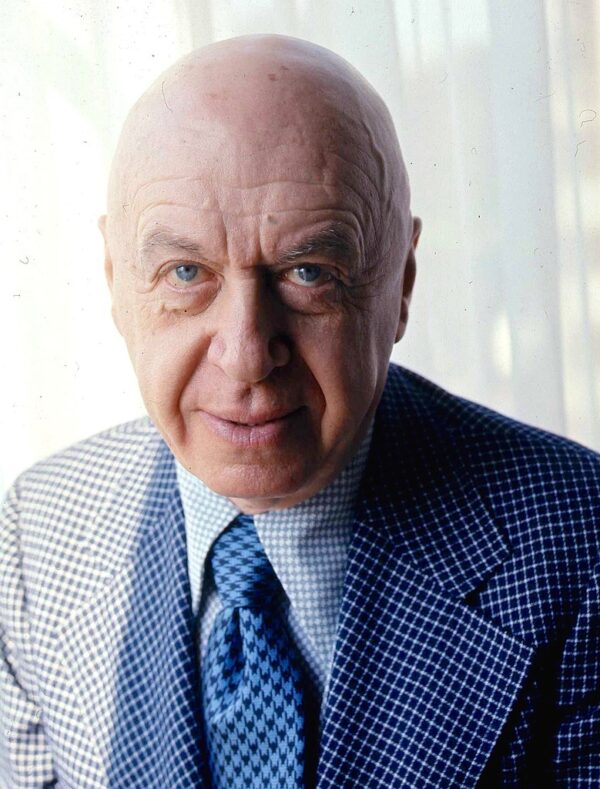

Foster was in his presence only once, in New York City in 1980, six years before his death. Foster remembers him well: “With his large, bald, ovoid head, piercing blue eyes, lips that formed a faint half-smile that seemed poised between charm and contempt, and his imperial bearing, Preminger radiated a lifetime of privilege, wealth, fame and power.”

Foster wrote this biography to “rescue” Preminger from his outsize persona and to present him in all his contradictory facets. “With his legendary temper on the one hand, and his dazzling Viennese charm on the other, he was like a character in an epic Russian novel. A man of many parts.”

Crediting Preminger with being an “industry pioneer,” Hirsch claims he was the first fully independent producer/director in Hollywood. Creating a template for the way movies are produced, he finished his films on or even ahead of schedule and never over budget. “Of his dependability, efficiency, financial common sense, managerial skill, and salesmanship, there was never any question,” Hirsch notes.

“Part of my attraction to Preminger was in the apparent contradiction between his temperament and the cool tone of his most commanding films,” he adds.

He went though three distinct phases. He was a contract director for Twentieth Century Fox from 1935 to 1936 and again from 1943 to 1953. He hit his stride as an independent director/producer from 1953 to 1967. And he seemed to lose his focus from 1968 to 1979, when he made his last picture.

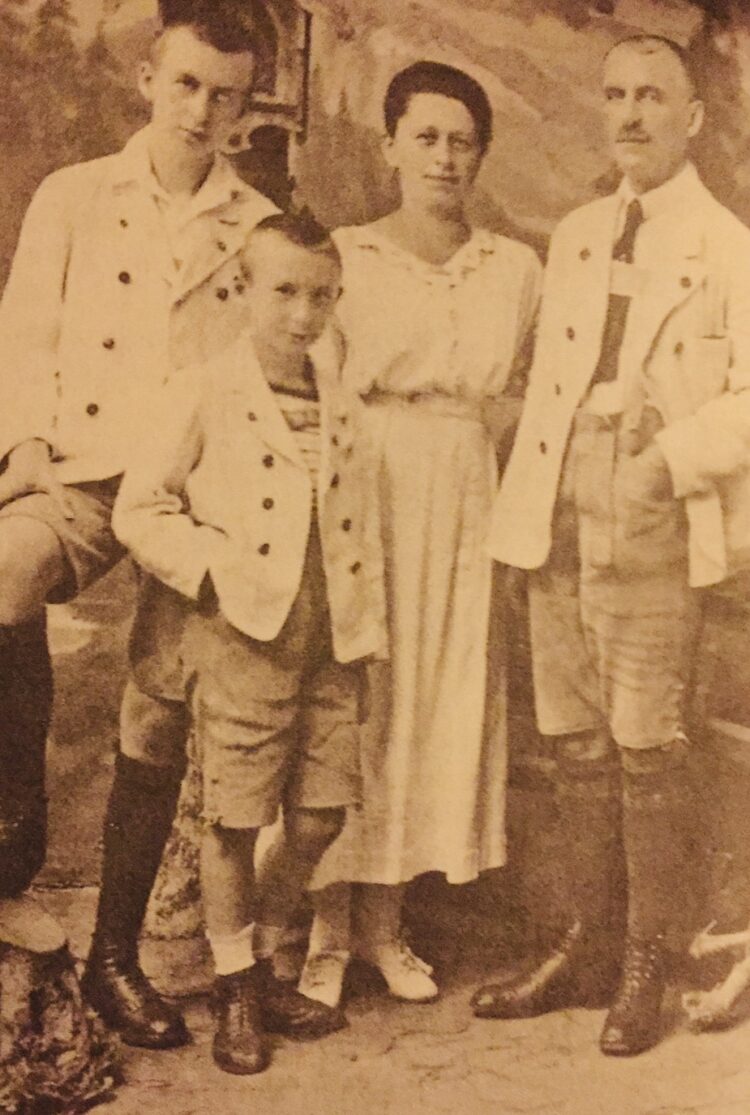

Preminger was born in 1905 in the Polish town of Wiznitz, which was then in Poland and which would later be claimed by Romania. Being snobbish, he presented himself as a native son of Vienna, where he lived from an early age. His father, Markus, was an industrious lawyer steeped in Germanic culture.

Preminger was drawn to the theater, and his assimilated, well-to-do family encouraged this interest. Preminger’s ambition was to become a stage actor, and thanks to his sturdy build, stentorian voice, penetrating eyes and sexual energy, he had a good shot at it. At 16, he won a minor role in an open-air theater production.

At his father’s request, he studied law while pursuing acting. But he soon realized he should be a director. Preminger branched into cinema in 1931 when he directed The Great Love. Though it opened to strong reviews and business, he dismissed it as fluff and returned to the theater.

He got his big break when Joseph Schenk, the president of the Twentieth Century Fox studio, invited him to Los Angeles in 1935. Preminger’s boss, Darryl Zanuck, was Schenk’s partner and a producer who had supervised the production of The Jazz Singer, the first talkie, and Little Caesar, a gangster movie that catapulted Edward G. Robinson to fame.

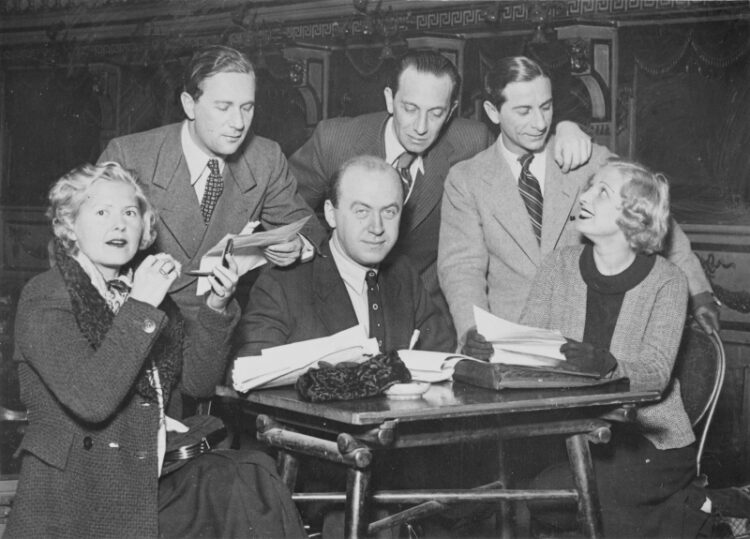

Preminger, in his debut picture, directed Under Your Spell, a low-grade screwball comedy that Hirsch describes as “a trifling B movie.” Preminger’s association with Zanuck was short-lived. They had an argument that degenerated into a shouting match, costing Preminger his job.

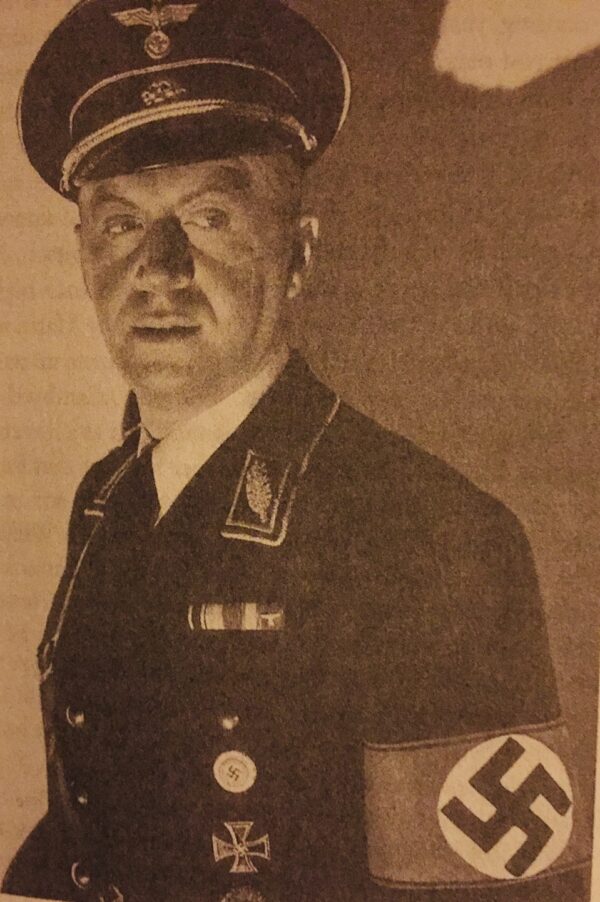

In 1938, when Germany annexed Austria and he was at the lowest point of his career, he brought his parents to the United States. He got a second chance when Lee Shubert hired him to direct a Broadway play. Then, in his Broadway acting debut, he played a Nazi villain in Clare Boothe’s play, Margin for Error. He portrayed another Nazi in The Pied Piper, a film that enabled him to return to Los Angeles.

William Goetz, who had succeeded Zanuck, offered him a seven-year contract as both an actor and director. In this capacity, he turned Margin for Error into a movie. It was released in 1943, the year he became an American citizen.

Laura, one of his better movies, came out in 1944, and it earned him an Academy Award nomination as best director. By 1946, he was earning $7,500 a week, then a princely sum.

Ingo, his brother, joined the industry as a talent agent, and he signed him up as one of his clients.

Throughout his book, Hirsch soberly analyses Preminger’s films. He believes that The Man with the Golden Arm, starring Frank Sinatra, has “grown hollow at the core” since its release in 1955. In his opinion, Anatomy of a Murder, is his “most poised” film, while Advise and Consent may well be “the most intelligent American film about American politics.” Preminger was at “the peak of his directorial abilities” when he made it.

Hirsch devotes an entire chapter to Exodus, whose storyline unfolds toward the end of the British Mandate period in Palestine. Preminger bought the rights to Leon Uris’ eponymous novel in 1958, and Arthur Krim of United Artists offered him $3.5 million in backing for what would be the first American film to be shot entirely in Israel.

“Otto was pro-Israel, but he did not share Uris’ hard-core Zionist stance, and in his film he was determined to modify the novelist’s anti-British and anti-Arab bias,” writes Hirsch. As a result, they had a falling out and their relationship floundered. Uris never spoke to Preminger again.

Preminger settled on blacklisted Dalton Trumbo as screenwriter, hoping he would be more objective than Uris. He was not disappointed. “I think that my picture is much closer to the truth, and to the historical facts, than is the book,” he would say.

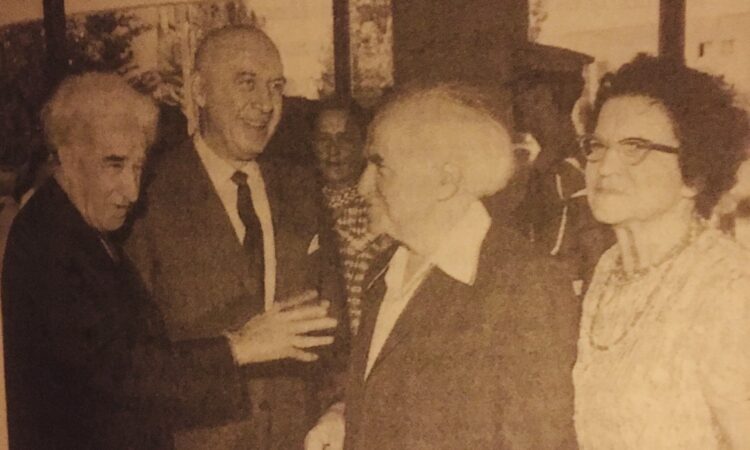

He enlisted the assistance of Meyer Weisgal, the president of the Weizmann Institute of Science, whom he had meet in Austria in 1924, as his “showrunner.” In exchange, Preminger promised the institute the Israeli royalties and the income from all the premieres around the world.

Three days before the start of shooting in March 1960, he married his costume coordinator, Hope Bryce, an Episcopalian. It was his third marriage.

As Exodus was filmed, Preminger came under pressure from a procession of Israelis to slant scenes in their favor or modify leading characters. Paul Newman, the actor who played the heroic Sabra Ari Ben-Canaan, sent Preminger suggestions for improving the script and the dialogue. When the film wrapped, he told Preminger he could have directed it better than him. Eva Marie Saint, who portrayed a Christian nurse, disliked Preminger and went to bed every night crying.

Exodus, finished in 13 weeks, was three hours and forty minutes in length. Its advance sales set a record. Hirsch is somewhat critical of Exodus, but offers an upbeat assessment of it. “Exodus does not fail its great subject. Working on a vast canvas, Preminger rises to the challenge, employing a more varied stylistic range than on any other film … Exodus, finally, is imbued with Zionist fervor. This powerful, important and under-appreciated film expresses the commitment of a Jewish director to a Jewish homeland.”

After Exodus, Preminger acquired the rights to Don Kurzman’s Genesis 1948: The First Arab-Israeli War, and announced that a film based on his book would be completed in 1973 to coincide with Israel’s 25th anniversary. The movie, Rosebud, opened in 1975 and was clobbered by critics.

Around this time, Preminger bought the rights to Moshe Dayan’s memoir, The Story of My Life. Accompanied by a screenwriter he had hired, they went to Israel to met Dayan, who was to be the film’s technical advisor. The movie never got off the ground.

Preminger’s last film, The Human Factor, based on a novel by Graham Greene and written by Tom Stoppard, was a critical success. “One of the best Preminger films in years,” wrote New York Times critic Vincent Canby. Hirsch agrees with his appraisal: “By any measure, his handling of The Human Factor demonstrates a serene command of the medium.”

Less than a year later, Preminger was stuck by a taxi as he crossed a busy street in Manhattan. The accident aggravated his growing frailty and may have contributed to the ministrokes that would afflict him. To make matters worse, he was diagnosed with colon cancer. He died on April 23, 1986.

In conclusion, Hirsch argues that Preminger’s legacy as a producer and director is secure. But he concurs with a perceptive critic who wrote, “He had become nearly as famous for his curmudgeonry as for his art.”