Women comprise slightly more than 50 percent of Israel’s population, yet they have been woefully underrepresented in the Knesset and in senior civil service positions.

Full gender equality is something that women in Israel still aspire to after 75 years of Israeli statehood, according to The Elected, a three-part series that starts on the ChaiFlicks streaming platform on September 7.

Among the accomplished women featured in this informative and thought-provoking film are Golda Meir, Israel’s first female prime minister; Merav Michaeli, the leader of the Labor Party; Shulamit Aloni, the human rights activist, and Pnina Tamano-Shata, the first Ethiopian member of parliament and the former minister of immigration and absorption.

For a long time, only 10 percent of parliamentarians in the Knesset were women, and they were often regarded as mere tokens. Golda Meir was one such person, a strong woman in a world controlled by men. And for decades, Israeli cabinets had only one female member.

In recent years, women have fared better. At last count, 77 men and 43 women comprised the Knesset’s membership. But as the above figures show, women still have a way to go before real equality is achieved.

The government bureaucracy is also top-heavy with men. Thirty three ministries are in charge of dealing with day-to-day affairs in government, yet only one one of its director-generals is a woman.

From the moment David Ben-Gurion declared Israeli statehood on May 14, 1948, women have had to fight for their rightful place in the political arena, a succession of women say in this sobering documentary.

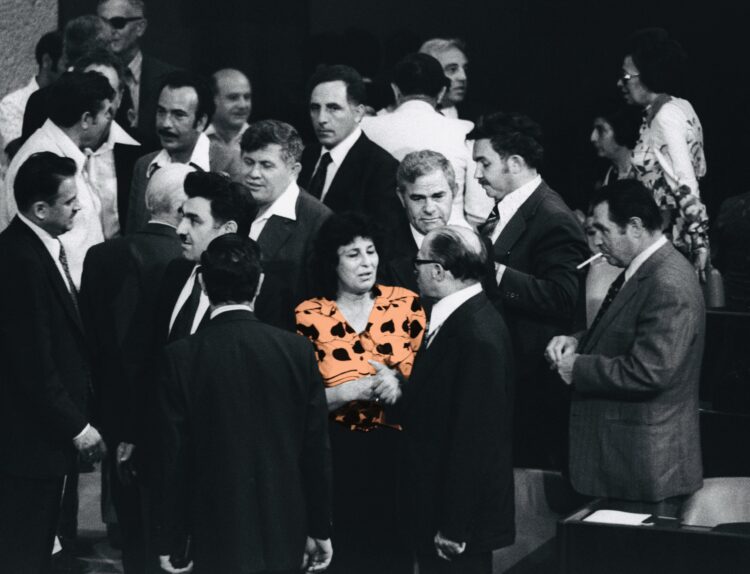

Sexism among men is certainly a major problem, but ultra-Orthodox resistance to equal rights is equally an obstacle. In archival clips, Ezer Weizman — the ex-commander of the air force and the former minister of defence — treats Geula Cohen, a member of the Knesset, with condescension. Meanwhile, Aryeh Dery, the leader of the Shas Party, refuses to answer a question from a reporter concerning the absence of women on his party’s list.

Dery’s chauvinism is hardly unusual among ultra-Orthodox politicians. One of them brazenly claims that women should not have the right to vote in general elections.

Only Yitzhak Shamir, a former prime minister and the then leader of the Likud Party, was unequivocally in favor of placing women in positions of power.

Limor Livnat, who served as a minister in several of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s governments, was 42 when she was first elected to the Knesset. Once there, she realized that the Knesset was essentially a “man’s world.”

Until then, she admits, she lacked the self-confidence to run for office. The temper of the times was such that women were discouraged from entering politics. “Too many men think they can do what they want,” she says ruefully.

Yael Dayan, the daughter of Moshe Dayan, the minister of defence during and after the Six Day War, was a member of the Knesset, where she was occasionally treated as a sex object. Infuriated by men’s attitude, she says they should not regard women as their personal property.

The late Marcia Freedman, an American who made aliyah and sat in the Knesset, fought for women’s rights and raised issues such as rape, domestic violence and abortion. More often than not, she was heckled and was the butt of jokes. Worn down by her adversaries, she retired and returned to the United States.

For decades, women in Israel were at a disadvantage because they were mostly stay-at-home mothers who did not even have bank accounts. Women’s expectations during that era were low. While men sought to be doctors, women aspired to be nurses, a difference which reflected the sexist hurdles in Israeli society.

Institutional problems continue to affect women. The Orthodox rabbinate, which exerts influence over domestic legislation, opposes gender equality legislation in principle. The military, from which future politicians are chosen, often restricts women to marginal jobs, thereby narrowing their opportunities after national service.

The battle against ingrained sexism in Israel took a great leap forward with the passage of legislation in 1992 outlawing sexual harassment. Its detractors claimed that its sponsors were upending the existing order. Still other men complained that women who wore “provocative” clothes were to blame for their troubles.

Miri Regev, a former brigadier-general and cabinet minister, is quoted as saying that women should learn the “rules of the game” if they wish to succeed in politics. But in another comment, she acknowledges that Israel is conservative and chauvinistic in terms of its values.

Far too often, the agendas of political parties do not align with the objectives of women. And in the view of Ayelet Shaked, a former justice minister, some glass ceilings simply cannot be broken. For example: a woman has never been minister of defence.

Tzipi Livni, the former leader of the centrist Kadima Party, came close to forming a government in 2009. But she failed because haredi parties would not back her.

Israeli women in politics have forged progress in the past 30 years, but there is still much to be done. That, in essence, is the overarching message of The Elected, a documentary that espouses and promotes gender equality.