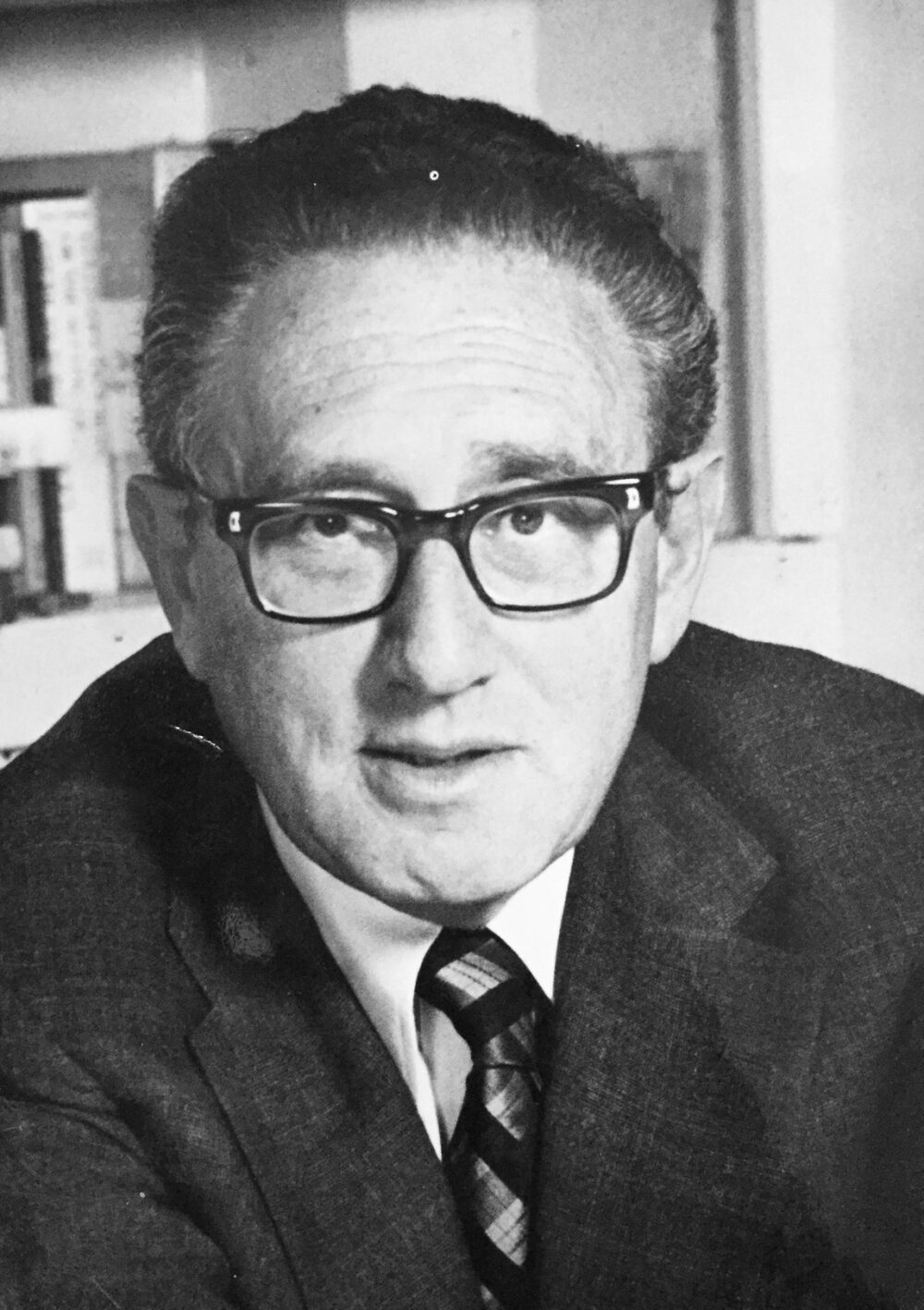

Henry Kissinger, the first Jewish U.S. secretary of state, celebrated his 100th birthday on May 27. The last surviving member of President Richard Nixon’s cabinet, he was among the most influential figures in the American foreign policy establishment during the last half of the 20th century.

A refugee from Nazi Germany, he arrived in the United States with his family in 1938, the year of the nation-wide Kristallnacht pogrom, which decimated the remnants of Germany’s Jewish community.

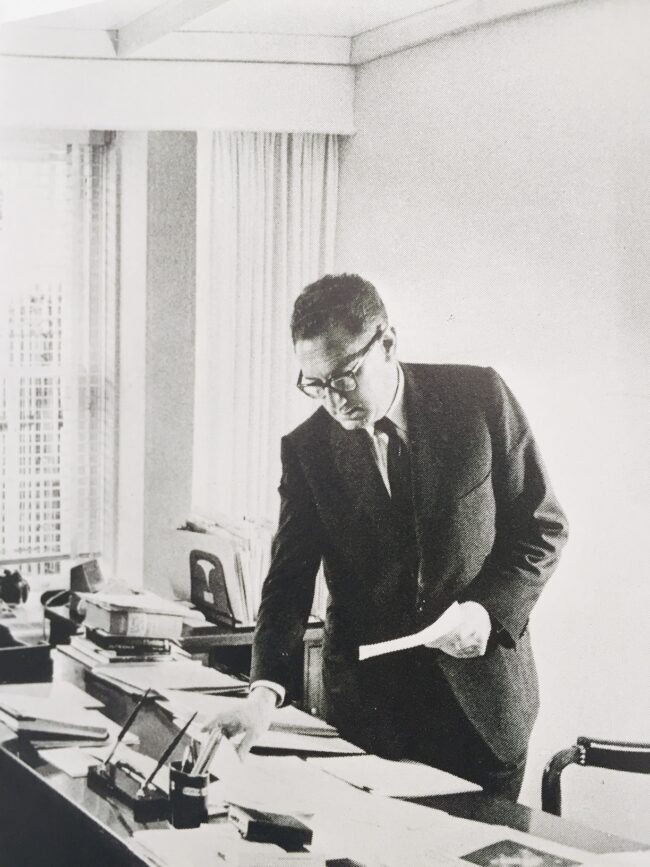

His first name back then was Heinz Alfred, yet Kissinger, who never lost his German accent, assimilated himself thoroughly into American society. He served in the U.S. army during World War II. In the 1950s, he was a Harvard University academic. Nixon hired him as his national security advisor in 1968.

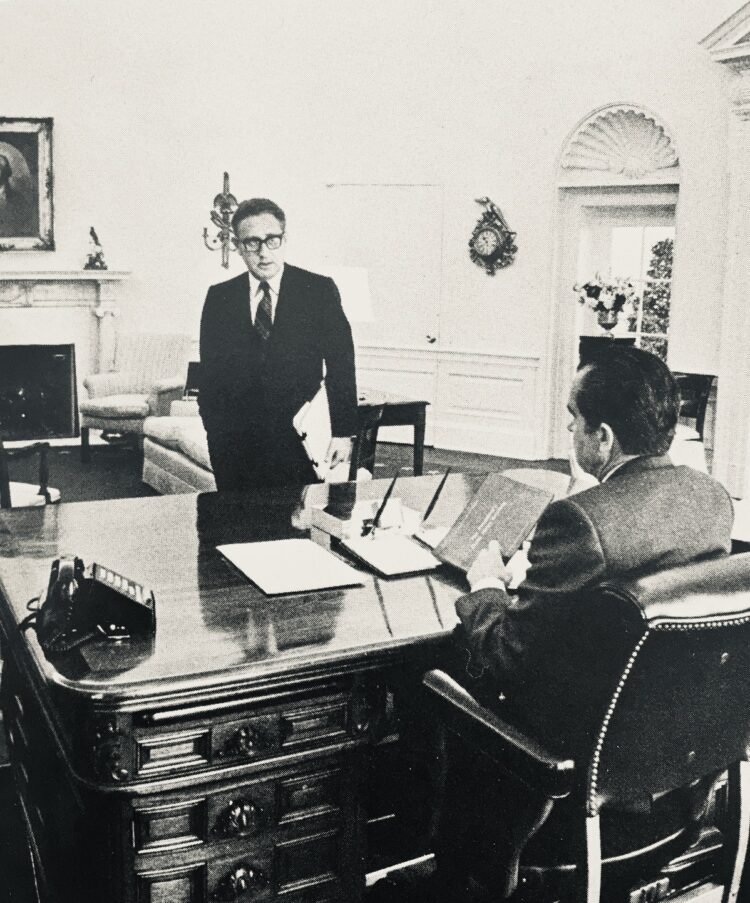

On the eve of the 1973 Yom Kippur War, Nixon appointed him secretary of state, a position he held under Nixon’s successor, Gerald Ford, until 1977.

A consummate practitioner of Realpolitik, he was instrumental in forging U.S. political and commercial relations with China and achieving detente with the Soviet Union.

During the lengthy war in Vietnam, he secretly ordered the bombing of North Vietnam’s military supply lines in Cambodia and Laos. In protracted talks in Paris, he reached a ceasefire agreement with the North Vietnamese government, for which he shared the Nobel peace prize. In 1975, the U.S.-backed South Vietnamese government in Saigon fell, paving the way for Vietnam’s reunification.

Kissinger supported a coup in Chile that resulted in the bloody ouster of Salvador Allende’s left-wing government. He tacitly supported Turkey, a NATO ally, when it seized one-third of Cyprus. And he spearheaded covert American involvement in the civil war in Angola, a former Portuguese colony.

Kissinger’s checkered record has prompted his harshest critics to denounce him as a war criminal. “The ugliest truth about Kissinger is that he isn’t a unique monster. He is an unusually plainspoken representative of a monstrous system of U.S. global hegemony,” claims a writer in the most recent edition of Jacobin.

True or not, Kissinger really made a difference.

Although he was not an expert in the Middle East, he invested a great deal of time and energy in the region from the late 1960s onward, and will doubtless be remembered for his brand of “shuttle diplomacy,” which produced two Israel-Egypt disengagement pacts, one truce accord between Israel and Syria, and a U.S. rapprochement with Egypt, which had been a Soviet client state for much of the 1950s and 1960s.

“When I entered office, I knew little of the Middle East,” he candidly admits in his memoirs, White House Years (1979). “I had never visited any Arab country. I was not familiar with the liturgy of Middle East negotiations … My personal acquaintance with the area before 1969 was limited to three brief private visits to Israel during the 1960s.”

But as he immersed himself in the “ambiguities, passions and frustrations of that maddening, heroic and exhilarating region,” his knowledge of it and of its leading personalities expanded exponentially and would be virtually unsurpassed.

Nixon suspected that Kissinger’s Jewish background “might cause me to lean too much toward Israel … He had his doubts as to whether my Jewish faith might warp my judgment.”

In Years of Upheaval (1982), the second volume of his memoirs, Kissinger addresses this issue head on: “Though not practising any religion, I could not forget that thirteen members of my family had died in Nazi concentration camps. I had no stomach for encouraging another holocaust by well-intentioned policies that might get out of control … And yet … I had to subordinate my emotional preferences to my perception of the national interest. Indeed, given the historical suspicions toward my religion, I had a special obligation to do so. It was not always easy. Occasionally, it proved painful. But Israel’s security could not be preserved in the long run only by anchoring it to a strategic interest of the United States.”

As Kissinger says in White House Years, Nixon learned to trust him. Under Nixon’s presidency, the United States “sought to reduce Soviet influence, weaken the position of the Arab radicals, encourage Arab moderates, and assure Israel’s security.”

Kissinger had an ambivalent view of the occupied areas Israel had seized during the Six Day War. “It naturally saw in the territories … an assurance of the security it had vainly sought throughout its existence. It strove for both territory and recognition, reluctant to admit that these objectives might prove incompatible.”

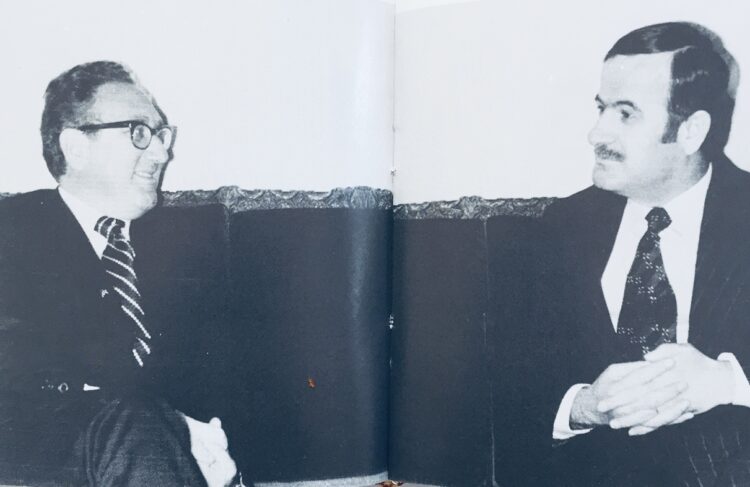

During these years, when the War of Attrition raged and Israel faced thousands of Soviet military “advisors” in Egypt and Syria, Kissinger met Israel’s key political figures.

Golda Meir, the then prime minister, left an impression. “She had a penetrating mind, leavened by earthiness and a mischievous sense of humor.”

Abba Eban, the foreign minister, impressed him with his dazzling verbal skills. “I have never encountered anyone who matched his command of the English language,” he writes. But in a sardonic aside, Kissinger says, “He practiced to the full his maxim that anything less than one hundred percent agreement with Israel’s point of view demonstrated lack of objectivity.”

He grew “extremely fond” of Yitzhak Rabin, then Israel’s ambassador to the United States. “His integrity and his analytic brilliance in cutting to the core of a problem were awesome. I valued his judgment.” But as he adds, “Rabin had many extraordinary qualities, but the gift of human relations was not one of them.”

In Years of Upheaval, Kissinger acknowledges that Nixon “shared many of the prejudices of the uprooted, California lower middle-class from which he had come. He believed that Jews formed a powerful cohesive group in American society; that they were predominately liberal; that they put the interests of Israel above everything else; that their control of the media made them dangerous adversaries; and that Israel had to be forced into a peace settlement and could not be permitted to jeopardize our Arab relations. None of this kept him from having cordial personal relations with many individual Jews and from elevating them in his administration to several key positions.”

Kissinger claims that Nixon “stood by Israel more firmly than almost any other president save Harry Truman. He admired Israeli guts. He respected Israeli leaders’ tenacious defence of their national interests. He considered their military prowess an asset for the democracies.”

He regarded the outbreak of the Yom Kippur War, his first test as secretary of state, as an intelligence failure. “We had become too complacent about our own assumptions. We knew everything but understood too little. And for that the highest officials — including me — must assume responsibility.”

In his opinion, the Soviet Union made no effort to stop the march toward war, though its intelligence agencies deduced that Egypt and Syria were planning an offensive against Israel to recapture the Golan Heights and the Sinai Peninsula.

Kissinger tried to attain two objectives: to prevent the Soviet Union from emerging as “the Arabs’ savior” and to “save” Israel if it encountered difficulty. “We could not permit Soviet clients to defeat a traditional friend. But once having demonstrated the futility of the military option, we would then have to use this to give impetus to the search for peace.”

When the Israeli armed forces ran short of weapons and munitions by the second week of the war, Nixon and Kissinger resupplied Israel. “In the first full day of the airlift we had more than matched what the Soviet Union had put into all the Arab countries … combined in all of the four previous days,” he writes in Years of Upheaval.

The war ended inconclusively, as he suggests: “Deep down, the Israelis knew that while they had won the last battle (in the Sinai), they had lost the aura of invincibility. The Arab armies were not destroyed.”

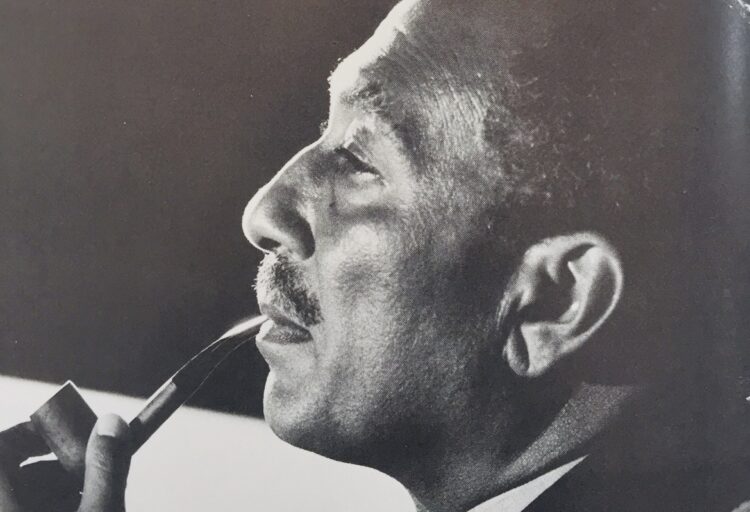

Kissinger engaged Egyptian President Anwar Sadat in talks to extend and deepen the truce. “Our exchanges with Cairo had convinced us that Sadat represented the best chance for peace in the Middle East.”

Rather than aiming at a comprehensive peace agreement, Kissinger opted for a “step-by-step” approach, which translated into two disengagement accords under which Israel gradually withdrew from the Sinai in exchange for Egyptian political gestures.

Kissinger had the utmost respect for Sadat: “He accomplished more for the Arab cause the those of his Arab brethren whose specialty was belligerent rhetoric. He recovered more territory, obtained more help from the West, and did more to make the Arab case reputable internationally than any of the leaders who regularly abused him …”

Kissinger’s final accomplishment before leaving office was coaxing Israel into signing its second disengagement with Egypt. Rabin, Israel’s prime minister, was reluctant to relinquish more territory in the Sinai, but Kissinger brought pressure to bear on him by withholding the delivery of aircraft to Israel.

On balance, Kissinger’s shuttle diplomacy was successful, eventually leading to Sadat’s historic trip to Jerusalem in 1977 and Israel’s peace treaty with Egypt two years later.

In the spring of 1974, as Israel and Syria fought a war of attrition on the Golan, Kissinger set out to produce a disengagement agreement between these enemies. It was a hard slog, with Kissinger shuttling indefatigably between Jerusalem and Damascus.

Hafez al-Assad, the Syrian president, was an extremely tough and shrewd negotiator, as Kissinger observes: “He had given us many a difficult moment. But I had witnessed how he had gone through the searing process of coming to grips with the problem of Arab-Israeli coexistence. He rebelled against the idea and yet had come close to accepting it.”

What Kissinger produced was impressive — decades of tranquility along Israel’s ceasefire line with Syria.

Kissinger doubtless contributed to Israel’s long-term security, but in all other respects, he was probably a disappointment to Jews.

He publicly supported President Ronald Reagan’s wreath-laying ceremony at a military cemetery in Bitburg, West Germany, where members of the Waffen-SS were buried.

He opposed the construction of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C. on the grounds that it might create “too high a profile” for Jews and “reignite antisemitism.”

In a taped conversation with Nixon shortly after his meeting with Golda Meir in 1973, he said that “the emigration of Jews from the Soviet Union is not an objective of American foreign policy, and if they put Jews into gas chambers in the Soviet Union, it is not an American concern,” though “maybe a humanitarian concern.”

Kissinger, too, was irked by the campaign that American Jews launched to expedite the emigration of Soviet Jews, lambasting the former as “self-serving bastards.”

Kissinger may have been a “conflicted” Jew, in the words of historian Gil Troy. But he was certainly a man of substance, a superior secretary of state who opened up new avenues of U.S. cooperation with China, stabilized bilateral relations with Russia, pulled American troops out of Vietnam, and contributed in large measure to what passed as peace and stability in the Middle East.

After his retirement as secretary of state, Kissinger formed a lucrative geopolitical consulting company, Kissinger Associates. And as an elder statesman, he provided advice to Republican and Democratic presidents.

Kissinger’s day in the sun is in the past, but some of his achievements have stood the test of time.