Tunisian Jews in Ruggero Gabbai’s bitter-sweet documentary, From TGM to TGV, look back at their lives in Tunisia and abroad with a mixture of nostalgia and angst. To be screened at the Toronto Jewish Film Festival on June 2, it examines the attitudes of Jews who were uprooted from their homeland.

Tunisia, an Arab state and a former French colony, was depleted of its Jewish population by a series of traumatic events from the birth of Israel in 1948 to the outbreak of the Six Day War in 1967.

One hundred thousand Jews lived in this North African nation when Israel declared statehood in 1948. Arab sympathy for the Palestinian cause and hostility to Israel prompted 40,000 Jews to emigrate. Sixty thousand Jews remained when Tunisia became an independent state in 1956, the year Israel invaded Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula in coordination with Britain and France.

Further Arab-Israeli wars, especially the Six Day War, infuriated Tunisian Arabs, leading to violence that drove out virtually every Jew in Tunisia. “Everything fell apart,” says an ex-Tunisian Jew. With Arabs equating local Jews with Israelis, they were perceived as enemies.

The vast majority of Jews immigrated to France, Canada and Israel, reducing Tunisia’s Jewish community to an empty shell. Merely 1,500 Jews live there today.

Strangely enough, Gabbai does not interview Tunisian Jews who immigrated to Israel or Canada. Nor does he mention the short-lived Nazi occupation of Tunisia, during which Jews were persecuted and deported.

The Tunisian Jews who spoke to Gabbai express a wide range of opinions about their former homeland.

Michel Boujenah, a singer, is extremely patriotic. “A Tunisian Jew is a Tunisian from birth to death, even if he moves to New York and starts speaking Russian,” he says in no uncertain terms.

David Khayat, an academic, is just as keen: “Tunisia is my parents and my parents are Tunisia.”

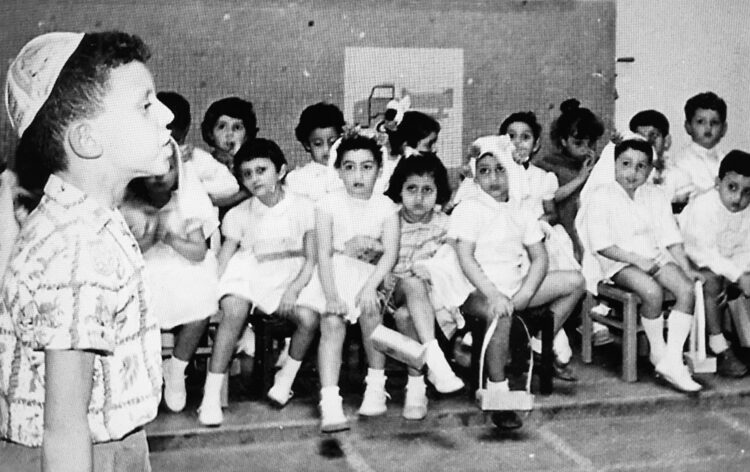

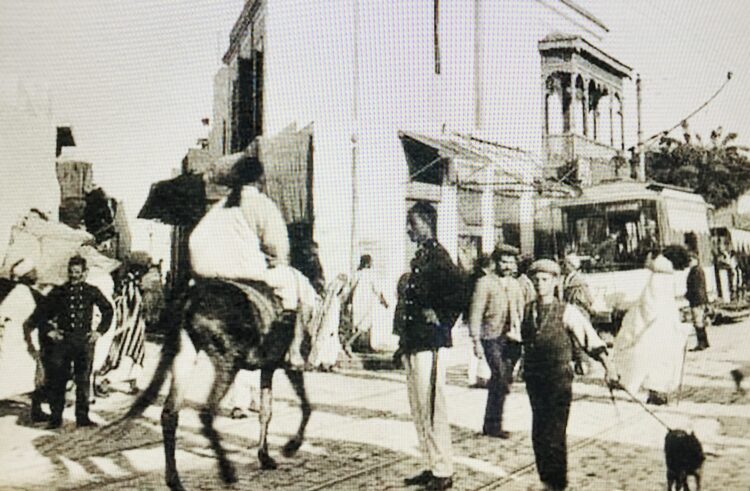

Tunisia’s Jewish community, among the oldest in the Diaspora, was formed after the destruction of the second temple in Jerusalem. At this point, the camera pans on La Goulette, a sedate seaside neighborhood in Tunis once inhabited by Jews, and on an elderly Arab who fondly remembers the era of Muslim, Jewish and Christian coexistence.

Victor Cohen, a former resident of La Goulette, happily recalls days at the beach, card games and parties. Still other Jews remember Jewish holidays and meals crowned by couscous meatballs. Everybody seems to have gotten along during that idyllic period.

This, of course, is only one side of a complex story, which Gabbai explores. As he suggests, Arabs and Jews did not necessarily live in harmony, with Arabs generally regarding Jews as Westerners, or outsiders, despite their profound roots in Tunisia.

In France, many of the Jewish newcomers had to start from zero, living in cramped flats and working at menial jobs. “My father was rich in Tunisia,” a man says. “In France, he was a butcher.”

Jewish refugees were seen as foreigners and in some instances they were the victims of French racism. A Jew was assailed as a “dirty Arab,” only to be denounced as a “dirty Jew” after protesting he was Jewish.

Still other Tunisian Jews in France are content. “Not for a second would I go back!” exclaims a woman. “France welcomed us very well,” says a man.

Albert Memmi, the late Tunisian Jewish writer who settled in France, says he feels neither French nor Tunisian.

However, a small number of Jews, like Jacob Lelluche, have returned to their original homes in Tunisia. Slim Zorgani, his young Arab friend, says he grew up thinking Jews were bad people. Today, they are perceived as “weird creature,” he adds. Younger Tunisian Arabs know nothing about Jews, he goes on to say.

Such is the atmosphere in Tunisia today that a young Jew nervously admits he never wears his yarmulke while visiting Tunis’ main outdoor market.

Moche Uzan, a Tunisian Jew whose family never left the country, feels the weight of history because, as the chief rabbi’s assistant, he has a special responsibility to preserve Jewish culture in Tunisia.

Rene Trabelsi is that rarest of Jew — a Tunisian politician who served as a government cabinet minister. Several years ago, he was the minister of tourism and transportation. He acknowledges that members of the opposition attacked him as a Jew.

Djerba, a small resort island off Tunisia’s coast where most Tunisian Jews live today, is featured briefly in the movie.

A Jewish woman, a silversmith, claims that Jews and Arabs get along well. “We love each other,” she claims.

Her comment should be taken with a grain of salt. Earlier this month, a Tunisian police officer fatally shot five people, including three policemen and two Jews, during the annual Jewish pilgrimage to Djerba’s historic synagogue. Tunisian President Kais Saied denounced the attack as “criminal and cowardly,” noting that Tunisia would remain safe for tourists in spite of attempts to “disturb its stability.”

The pilgrimage in Djerba was previously targeted in 2002 in an Al Qaeda truck bombing that killed 21 mostly German and French tourists.

These attacks underscore the fact that certain elements in Tunisian society are profoundly antisemitic