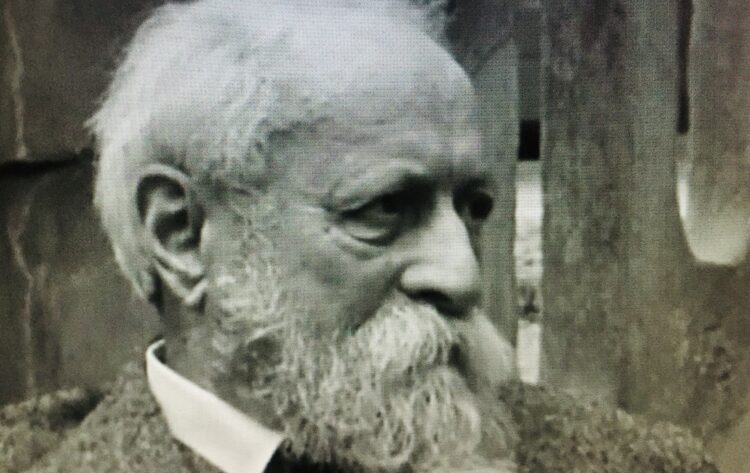

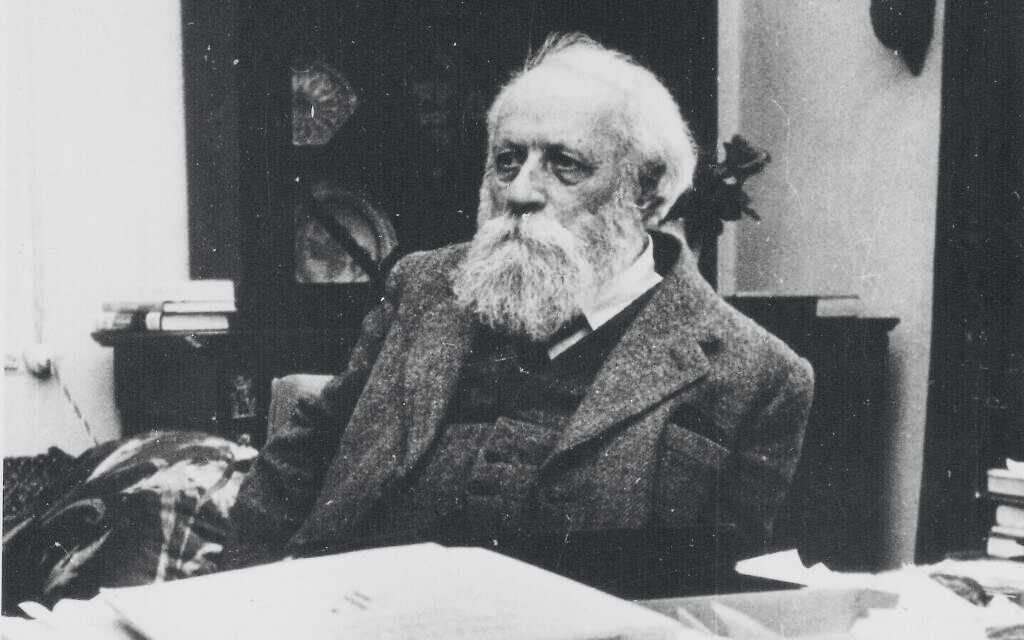

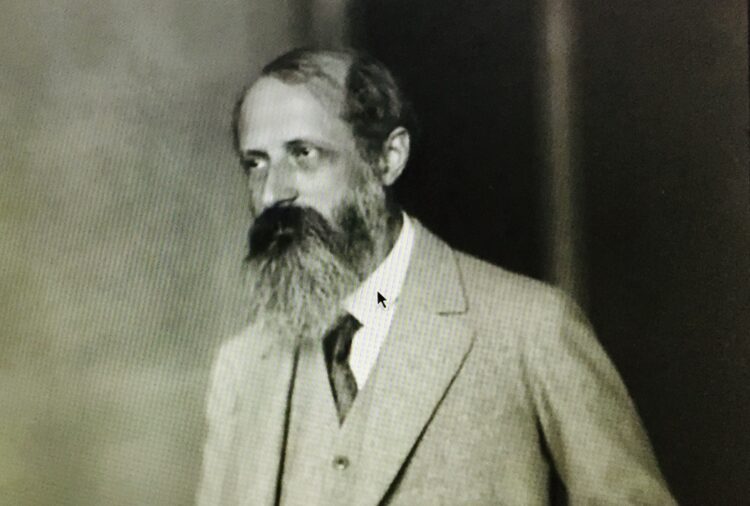

The philosopher Martin Buber (1878-1965) never deviated from his belief that dialogue is an essential component of human existence. A cosmopolitan bridge builder, he devoted his life to two interrelated goals — reconciliation between people and universal peace.

It is hardly coincidental that he was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize seven times.

Buber’s quest forms the theme of Pierre-Henry Salfati’s thoughtful documentary, Martin Buber: Itinerary of a Humanist, which is now being screened online by the Toronto Jewish Film Foundation.

Buber, who was born in Vienna and died in Jerusalem, disseminated his imperishable ideas through monographs, books, lectures, discussions and letters.

The author of the classic work I and Thou, he was an indefatigable letter writer, having written 50,000 letters during his lifetime. He corresponded with the most brilliant minds of the day, from Franz Kafka and Jean-Paul Sartre to Albert Camus and Mahatma Gandhi. Much of his correspondence has been preserved and is now stored in the Hebrew University’s main library.

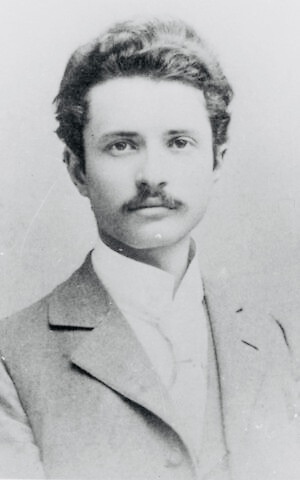

The scion of a long line of rabbis, Buber spent his youth in the Austro-Hungarian city of Lemberg, which was inhabited by Ukrainians, Poles and Jews, among others.

His first teacher, his grandfather Salamon, was a merchant, banker and scholar whom he considered his role model. Until the age of ten, he was home schooled by his grandmother. His father, Karl, a horse dealer, is hardly mentioned in the film, except in the seminal role he played in introducing him to the world of Hassidism, which had a profound influence on Buber’s thinking.

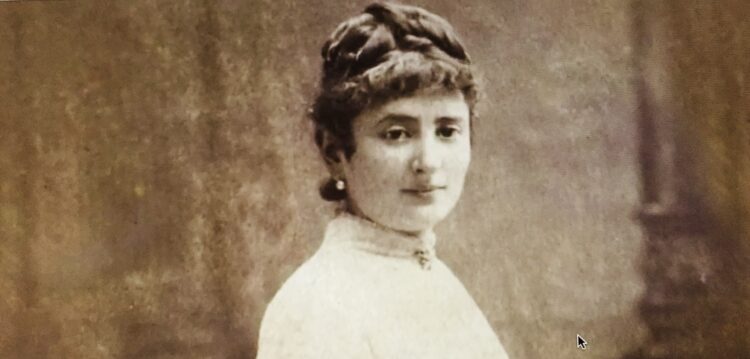

Buber’s wife, Paula, a German Catholic convert to Judaism and an intellectual in her own right, was his soul mate and kindred spirit. She strengthened his attachment to Judaism, and in tandem, they collaborated closely on a whole host of academic projects, as their hand-written notebooks attest.

From 1916 to 1938, they lived in the German town of Heppenheim. During part of this period, he was a professor at Frankfurt University. Despite the persecution of Jews during the Nazi era, Buber was reluctant to leave Germany. He finally departed in 1938, when Kristallnacht broke out. These nation-wide pogroms spelled finis to Germany’s Jewish community.

He and his family immigrated to Palestine, where he would teach at the Hebrew University. Buber, one of its founders, was a cultural Zionist who sought to create a spiritual homeland for Jews in Palestine. Unlike Theodor Herzl, the founder of political Zionism, he was not a Jewish nationalist.

From 1925 onward, along with Judah Magnes, Albert Einstein and others, he called for a binational state that Jews and Arabs could share on an equal basis. Brit Shalom, the organization that promoted this utopian idea, enjoyed limited popularity among Jews in Palestine.

After World War II, Buber worked to achieve friendship between Jews and Germans, a cause that relatively few Israelis were prepared to embrace so soon after the end of the Nazi regime.

Being opposed to capital punishment, Buber urged Israeli Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion to commute the death sentence of convicted Nazi war criminal Adolf Eichmann, but to no avail.

As the film suggests, Buber was something of an iconoclast, a man who went against the grain of conventionality.