Known as the Angel of Death, he was the personification of Adolf Hitler’s Nazi regime and the embodiment of the Holocaust.

Josef Mengele, a minor yet haunting figure in Nazi culture, was a German physician who cold-bloodedly determined the fate of new Jewish arrivals at the Auschwitz-Birkenau extermination camp in Poland and who conducted cruel and gruesome medical experiments on some of the prisoners.

Mengele is the object of David Marwell’s comprehensive and lucid biography, Mengele: Unmasking the Angel of Death (W.W. Norton & Company).

Marwell is one of the leading authorities on this iconic Nazi figure, having been chief of research at the U.S. Department of Justice’s Office of Special Investigations, which was established in 1979 to track down Nazis in the United States. In 1985, five years after joining the unit, Marwell was assigned to the task of locating Mengele and bringing him to justice. By then, he had been dead for six years, having died in the winter of 1979.

Marwell has delved deeply into Mengele’s mendacious career, having read his correspondence, interviewed his family, friends and colleagues and visited the scenes of his crimes. And so his book may well be the definite account of Mengele’s life.

Born in the southern German town of Gunzburg on March 16, 1911, he was the son of Karl Mengele, a prosperous manufacturer of farm equipment. Brought up in a conventional and conservative Catholic family, Mengele left his hometown in 1930 to study medicine, human genetics and anthropology at Ludwig-Maximilian University in Munich.

Three years later, following Hitler’s accession to power, his father joined the Nazi Party. Mengele himself had been a member of the Greater German Youth League, which barred Jews from membership. He was also a disciple of Franz Hamburger, a doctor who was a proponent of euthanasia for babies with physical or mental disabilities, and a pupil of Theodor Mollison, an anthropologist who believed in the inferiority of some races.

As Marwell suggests, Mengele was enormously influenced by his mentors, who were in the forefront of “the racial struggle at the heart of the Nazi worldview.”

In 1937, following an internship in Leipzig, he enrolled at the University of Frankfurt’s Institute for Hereditary Biology and Racial Hygiene, where he came under the baneful influence of the physician and eugenicist Otmar von Verschuer, an ardent Nazi who, like Hitler’s deputy Rudolph Hess, believed that Nazism was “applied biology.”

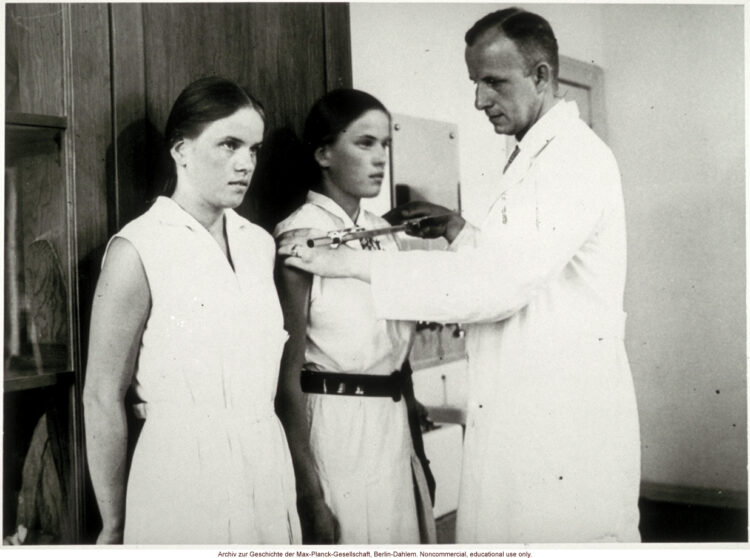

Verschuer hired him as his assistant in 1938, the year Mengele joined the SS. One of his tasks was to render professional judgments about a person’s paternity and “racial acceptability” in light of the 1936 Nuremberg Laws, which stripped Jews of their German citizenship and classified them on the basis of their racial identity.

Transferred to Nazi-occupied Poland in 1940, Mengele was given the job of evaluating the racial characteristics of ethnic Germans. From there, he was posted to the Fifth Wafen-SS Viking Division, which was composed of Scandinavian, Dutch and Flemish volunteers. It murdered thousands of Jews in the Soviet Union, but there is no evidence that Mengele himself participated in these crimes.

Mengele was sent to Auschwitz-Birkenau in 1943. He and other physicians carried out “selections,” deciding which newly-arrived prisoners would be gassed immediately and which ones could first be exploited for their labor.

Mengele and his companions conducted a deadly array of experiments. They perfected a method for mass sterilization, which the Nazis intended to use on Slavs and Germans of partial Jewish ancestry. They conducted experiments on the effects of starvation and on the efficacy of certain drugs. And they experimented with twins so as to increase the German birthrate and thereby consolidate the “master race.”

The arrival of more than 400,000 Hungarian Jews in 1944 offered Mengele unsurpassed opportunities to carry on his diabolical experiments.

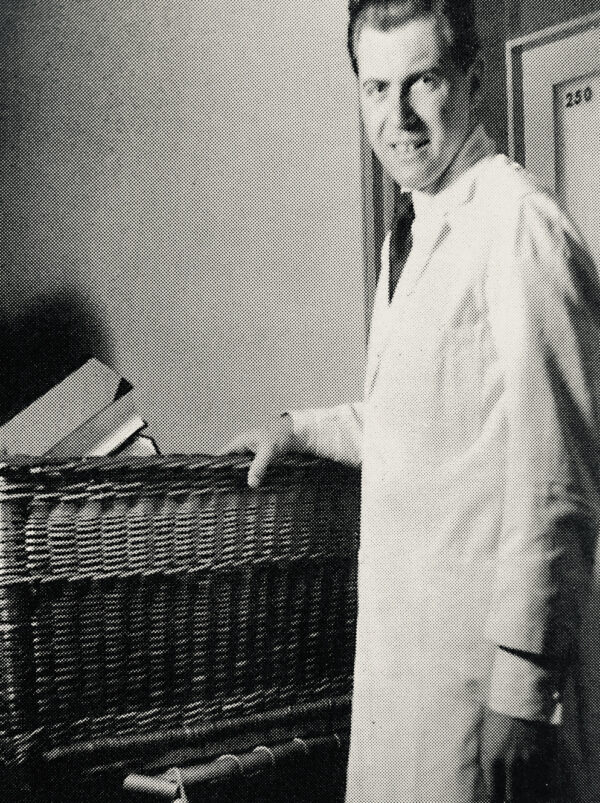

As Marwell writes, Mengele thrived at Auschwitz-Birkenau. His supervisor was pleased with his performance. “Dr. M has a straight-forward, honest and stable character,” he wrote in a glowing report. “He is absolutely reliable, upright and straight in his demeanor. His mental and physical dispositions can be described as outstanding.”

Mengele’s wife, Irene, claimed after the war that she had been unaware of her husband’s work and had never entered the camp. She regarded it as “bleak and desolate” and said she had enjoyed bathing in the nearby Sola River and picking blackberries, which she made into a marmalade. In praise of Mengele, she said he was “always charming, funny (and) very social.”

With Germany’s defeat, Mengele went into hiding under the assumed name of Fritz Hohmann. He found work on a farm in the foothills of the Bavarian Alps and remained there for the next three years, leading the American occupation authority to conclude he was dead.

Mengele’s family business was virtually untouched by the war. It prospered as western Germany emerged from the ashes of the Third Reich.

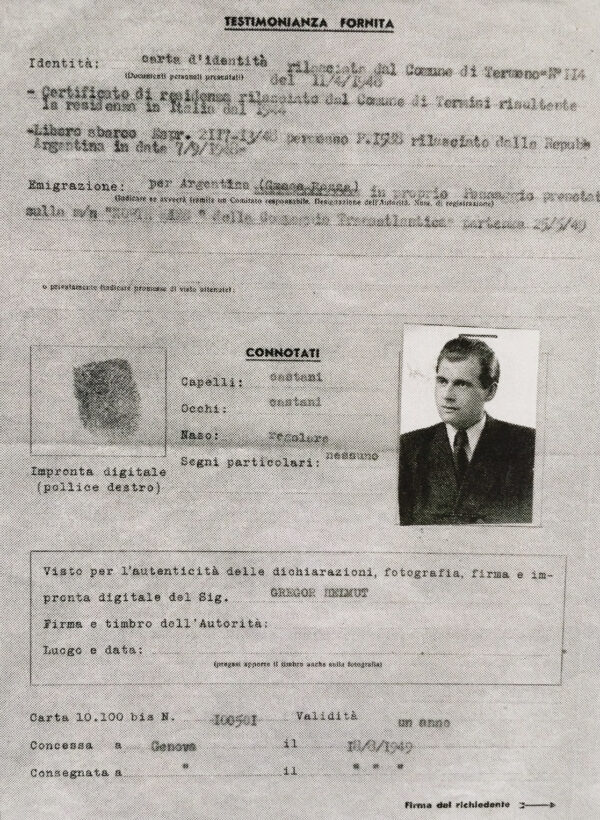

During this unsettled period, Mengele decided to leave Europe, assuming he would never be able to resume a normal existence there. He arrived in Argentina in the summer of 1949 under the pseudonym of Helmut Gregor, and lived in safety in Buenos Aires for nearly a decade.

Nazi sympathizers helped him to adjust to the new environment, and his family back in West Germany provided him with significant financial support, enabling him to successively start a wooden toy business and a pharmaceutical company. His father visited him at least twice. His wife, refusing to follow him to Brazil, filed for divorce.

Through Willem Sassen, a Dutch Nazi collaborator and a journalist, Mengele met Adolf Eichmann, one of the architects of the Holocaust. Returning to science, he published an article on genetics in a local German-language magazine.

Buoyed by his success in Argentina, he assumed his real identity as Josef Mengele. In 1956, the West German embassy provided him with a passport in his real name. But just three years later, in a volte-face, the German government asked for his extradition. In 1960, an Argentinian judge issued an order for his arrest. Meanwhile, the Mossad, Israel’s external intelligence agency, began searching for him.

By this juncture, says Marwell, Mengele had settled in neighboring Paraguay and had obtained Paraguayan citizenship. He had no trouble settling in Paraguay, which was ruled by Alfredo Stroessner, who had family roots in Bavaria. Mengele had friends and contacts in Paraguay, which prohibited the extradition of its citizens.

Much to Mengele’s disappointment, the University of Frankfurt, his alma mater, rescinded his medical degree in 1961, having concluded he was “unworthy” of it. Marwell speculates that the university’s decision had a profound effect on him and distanced him even further from his homeland.

After Israel’s abduction of Eichmann in 1960, Mengele feared he would be tracked down in Paraguay by the Mossad. He fled with an identity card in the name of Peter Hochblicher. It was supplied by Hans-Ulrich Rudel, who had been a decorated Luftwaffe colonel. Mengele lived in Sao Paulo, working in a textile plant. Later on, he managed a coffee plantation owned by a German couple.

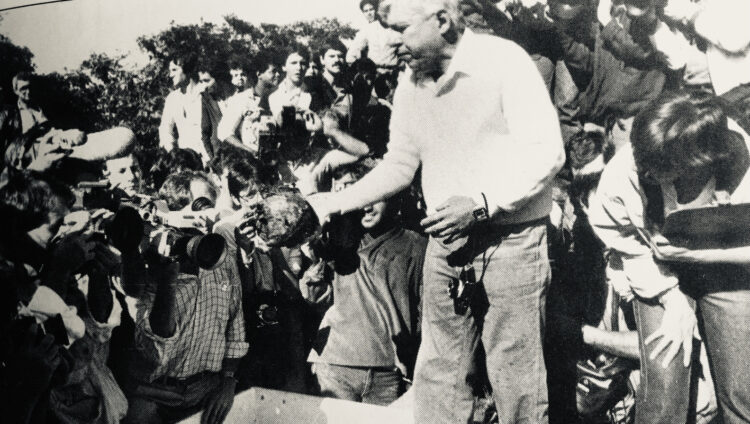

In 1985, West Germany, the United States and Israel agreed to combine their resources to find Mengele. Shortly afterward, the Ministry of Justice in the German state of Hesse reported that Mengele had probably died in 1979. A German couple that knew him confirmed he had drowned on a beach in the town of Bertioga.

Mengele’s corpse was exhumed in a Sao Paulo cemetery under the supervision of a Brazilian forensic pathologist, and tests proved it was Mengele.

His son, Rolf, extended his “deepest sympathy” to all of his father’s victims, and then sold Mengele’s correspondence and notebooks to the German magazine Bunte for a hefty sum.

In the wake of his exhumation, Israel stopped looking for Mengele. However, Dov Shilansky, the former speaker of the Knesset, insisted that the body that had been retrieved from the grave was not Mengele’s.

Marwell does not buy this claim. As far as he is concerned, the Mengele case is closed.