Upwards of one million Polish citizens were deported to Siberia by the Soviet Union following its invasion of eastern Poland more than 80 years ago. But in an astonishing twist of fate, some 20,0000 of these refugees left Siberia shortly afterward and migrated to six African countries, bringing a chunk of Poland in their baggage.

Jonathan Kolodziej Durand’s late grandmother, Kazimierz Kolodziej (nee Gerech), was one of them. Uprooted from her home in what is now Belarus at the age of 11, she spent six years in the tropics in a refugee camp in Tengeru, Tanzania. She appears in her grandson’s documentary, Memory Is Our Homeland, which will be screened in Toronto at the Hot Docs Ted Rogers Cinema on February 29 at 1:15 p.m. and again at the Revue Cinema on March 1 and 8.

Durand’s meditative and absorbing one-and-a-half hour film, shot in Africa, Canada and Britain, is augmented by on-camera interviews, personal photographs, home movies and World War II newsreels. It’s about memory and family history and is rooted in deportation, exile and renewal.

Poland, having been partitioned by Russia, Prussia and the Austro-Hungarian Empire in the late 18th century, regained its independence in 1918 in the wake of World War I. Poland’s sovereignty was short-lived. Western Poland was conquered by Germany on September 1, 1939. Only 16 days later, the Red Army invaded eastern Poland, which was summarily incorporated into the Soviet Union.

Durand’s grandmother and her family lived in Ostrowek when the Soviets pulled into her village. It was close to Ruzhany, where she had been baptized. Prior to the war, three-quarters of Ruzhany’s population had been Jewish.

Before this catastrophic year ended, the Soviet government deported hundreds of thousands of the region’s inhabitants to forced labor camps in Siberia in an attempt to de-Polonize these border lands. Children were sent to Soviet schools to be indoctrinated. By Durand’s estimate, 55 percent of the deportees were ethnic Poles, 30 percent were Jews and most of the rest were Belarusians.

Life in Siberia was difficult. “I still remember eating the grass, I was so hungry,” says a Polish woman.

The Poles in Siberia were permitted to leave the Soviet Union after the German invasion on June 22, 1941. They headed southward in the hope of meeting General Wladsyslaw Anders’ Polish army, which was bound for Palestine, a British colony and a former province of the Ottoman Turkish empire.

More than 100,000 of the Polish refugees passed through Iran en route to British colonies in eastern Africa Durand’s grandmother’s journey ended in Tengeru — a remote village in Tanzania — in 1942.

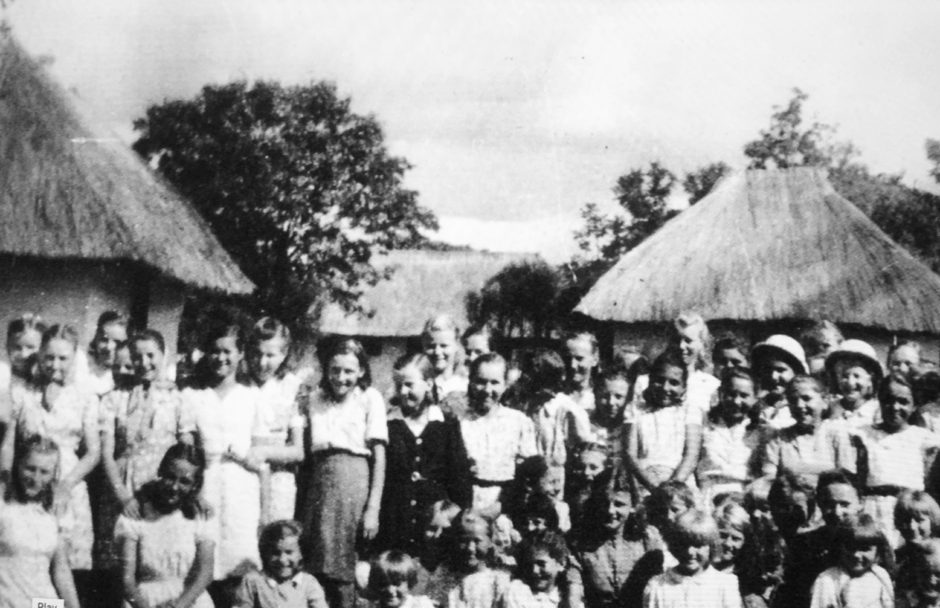

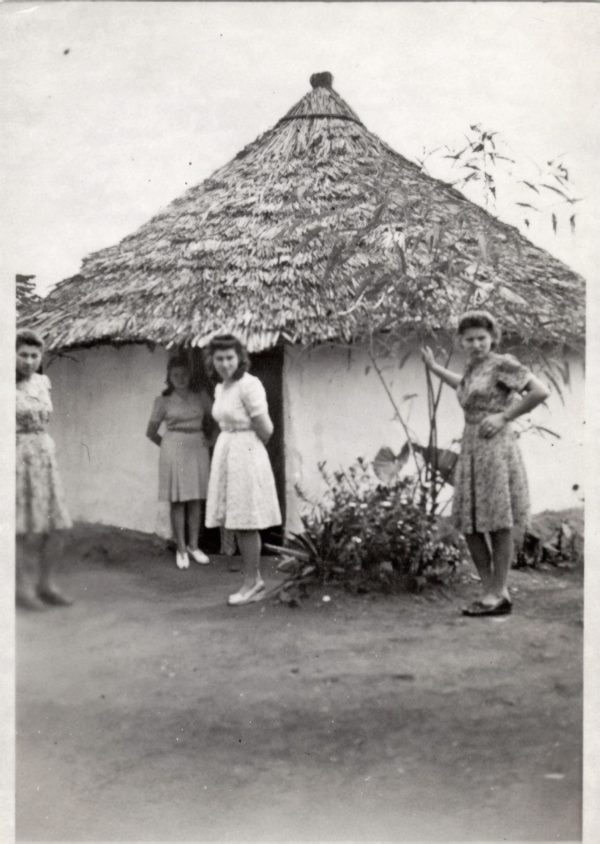

The remainder of the Poles were sent to two dozen villages in five neighboring countries: Kenya, Uganda, Zimbabwe, Zambia and South Africa. In Tengeru, they lived in primitive huts with thatched straw roofs. According to Durand, 30 of the Poles, including one of the camp doctors, were of the Jewish faith. In his film, the camera briefly pans on several tombstones in a cemetery emblazoned with the Star of David.

Regardless of their respective religions, the newcomers were hard-pressed to accustom themselves to Africa, which must have come as a cultural shock to them. The indigenous people were physically, culturally and religiously very different. The climate was tropical. The landscape was a palette of colors they had never seen. In short, Africa was thousands of kilometers from the blood-soaked battlefields of Europe and the cold and darkness of Siberia.

However disoriented they felt, Africa was quiet and safe.

At first, the Africans were afraid of the new arrivals, but eventually Poles and Africans fraternized, in contravention to British rules. Yet Africa was not really “home,” as Durand’s grandmother says. It was regarded as a haven until such time as Poles could return to Poland. But after Poland fell into the Soviet orbit and was communized, few, if any, of the refugees sought to go back. They restarted their lives in a host of other countries. Durand’s family resettled in Canada. His grandmother’s sister chose Britain.

Durand says he made Memory Is Our Homeland because the story of the Poles in Africa, an exotic footnote in the historiography of the Polish diaspora, has been all but forgotten. Durand’s film is proof that this intriguing chapter will not be erased from the consciousness of Poles.