With immigrants from all corners of the world pouring into Canada in the decades after World War II, Toronto was in desperate need of new residential housing. The construction industry met the challenge, erecting some 500,000 rental apartment units from 1952 to 1975. Virtually all of them were built by Jewish builders, a few of whom were immigrants and Holocaust survivors.

Ron Chapman’s upbeat documentary, Shelter, an amalgam of interviews, photographs, file footage and reenactments, tells this little known but important story with zest and vigor.

It will be screened online at the Toronto Jewish Film Festival, which runs from June 3-13.

Two of the major developers, Mendel Tenenbaum and Sam Brown, were survivors of the Shoah from Poland. Among their Canadian-born counterparts were John Daniels and Eph Diamond. They constituted a formidable force, altering the urban landscape of Canada’s biggest city and providing affordable housing for newcomers.

The companies they owned and managed included the Greenwin Group, Cadillac Fairview Corporation, the Daniels Group, the Brown Group and the Tenen Group.

To a man, they were dyed-in-the-wool entrepreneurs whose energy, work ethic and vision were the envy of the industry.

“When I came to Toronto, there were not big buildings, nothing,” says Tenenbaum, a survivor of the Auschwitz-Birkenau extermination camp.

This, of course, is an exaggeration, but his point is well taken. Builders like Tenenbaum filled a niche and profited handsomely by it.

When Tenenbaum arrived in Canada, open antisemitism was quite common and certain employment opportunities were beyond the reach of Jews, Diamond’s wife, Shirley, recalls. “Eph was a builder because he couldn’t get a job as an engineer. In those days, our people weren’t very welcome in that field.”

Independent Jewish builders did not have to contend with such raw prejudices. And banks were only too glad to lend money to hard-working Jewish real estate developers.

Their modus operandi was to buy a property or a piece of land collectively and flip it for a higher price. In general, they had a good intuitive feel for the market. As they gained knowledge, experience and self-confidence, they graduated from building single-family dwellings to erecting rental apartments and sub-divisions.

The construction business was more than just a matter of bricks and mortar for dedicated and resourceful people like Tenenbaum. “It was his life,” says his daughter, Sally.

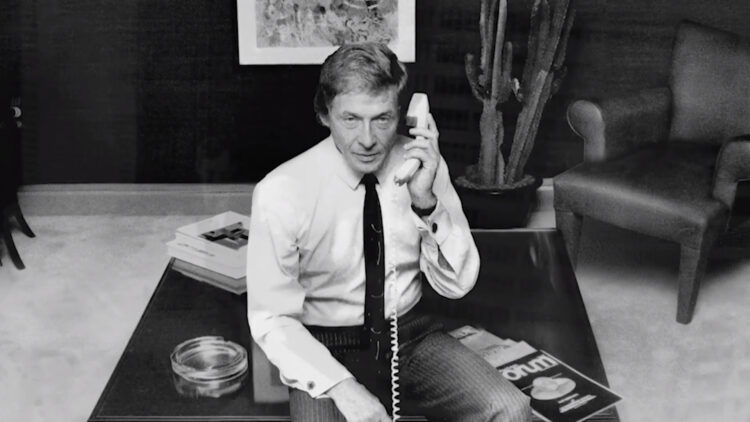

Apart from Tenenbaum, Brown and the rest, one of the key figures in Toronto’s postwar real estate bonanza was Eddie Cogan, a consummate deal maker who was widely known and admired as a “rainmaker.” As one observer put it, “He could see the future of things.”

On Saturday mornings, they would usually meet for breakfast at Stubbys, a now-defunct hole-in-the-wall restaurant on Bathurst Street, to talk shop and make deals.

Thanks to them, tens of thousands of people in Toronto found a decent place to live.