Peter Mostovoy’s bitter-sweet autobiographical movie, The Red Scarf, exposes the hypocritical pretensions of a society that celebrated egalitarianism and brotherhood but that denied equal opportunities to one of its national minorities.

It will be screened online by the Toronto Jewish Film Festival, which runs from June 3-13.

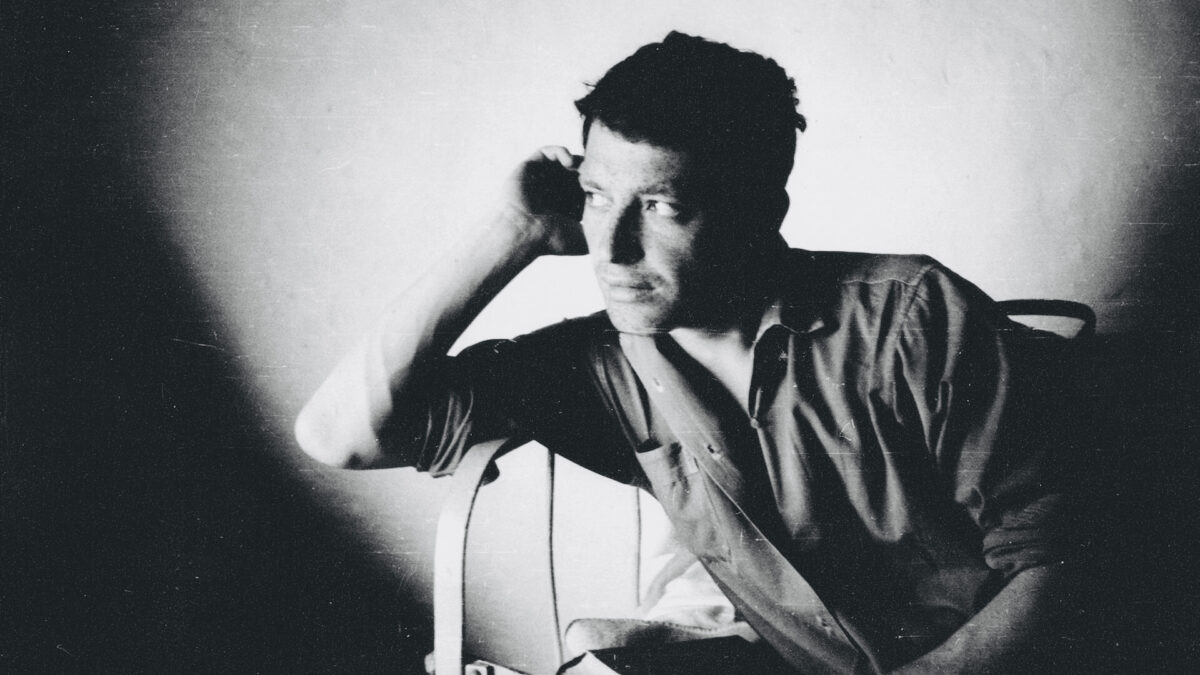

Mostovoy, a cinematographer and director, is a distinguished filmmaker, having made two feature films and more than 40 documentaries. The son of a Red Army officer, he set out to be a scientist, but was drawn to cinema after watching an inspirational Soviet movie.

As he discovered as a young adult, a Jewish person in the Soviet Union had no alternative but to lower his or her career expectations due to the prevalence of antisemitism, which had been outlawed by the Communist regime early in its history.

Mostovoy, born in 1938, had a contented childhood. Like so many of his contemporaries, he did not realize his motherland was governed by a totalitarian system that brooked no dissent and favored ethnic Russians.

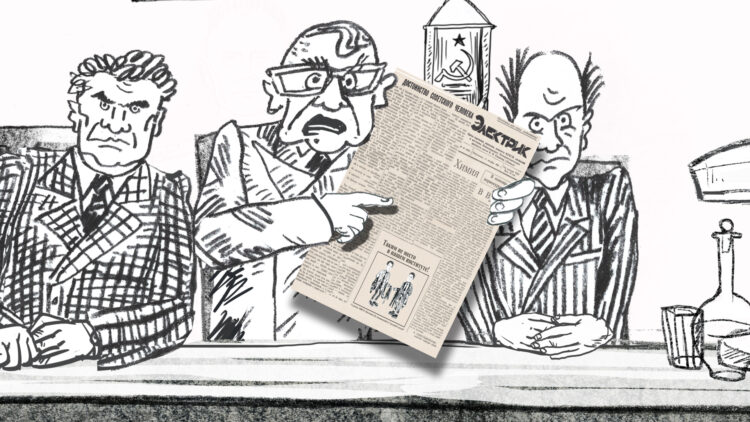

In 1960, in his final year of studies at a scientific institute in Leningrad, he and a friend decided to earn a little pocket money by selling a used jumper at a weekly flea market. To attract a buyer, they did something unusual for the times. They made an innocuous poster advertising their product. Much to their surprise, they were arrested, taken to KGB headquarters, and informed they had broken the law.

Mostovoy’s non-Jewish friend was given the opportunity to recant for this misdemeanor, but he remained defiant. Mostovoy, however, was immediately labelled as “untrustworthy.” In short order, he and his friend were expelled from the institute, and he was conscripted into the navy.

His father, a major and a war veteran, intervened. He convinced a panel of judges that his wayward son was a “true” Soviet patriot. Assigned to work in a factory for a year, Mostovoy was subsequently reinstated by the institute. He received his diploma and accepted a job at a scientific research facility.

Mostovoy was smitten by films after seeing a legendary Soviet movie, The Cranes Are Flying. He submitted an application form to a cinematography school and passed the entry exam, only to be told there was a place for only one Jew per academic session. Another Jewish applicant was accepted, and Mostovoy was crushed.

Undeterred by the stinging rejection, he and a friend produced an independent documentary, Living Water, about Leningrad’s white nights in summer. Finished in 1965, it won prizes at amateur film festivals. Mostovoy showed it to the director Valery Solovtzev, who was impressed by its craftsmanship.

He hired Mostovoy as a cameraman’s deputy assistant, a position that enabled him to land a job as a cinematographer with another director, Pavel Kogan. He was making a film about the fabled Hermitage Museum. Kogan’s documentary, Look At the Face, won renown.

He and Mostovoy teamed up again to make a film about bohemian cafe life in Leningrad, but the studio that had commissioned it found it politically appalling and ordered it to be destroyed. Mostovoy kept an unregistered copy.

In 1968, Mostovoy directed his first film, Only Three Lessons, which earned the top prize at the Krakow International Film Festival. Mostovoy moved to Moscow in the early 1970s, but no movie studio was willing to hire him, claiming his films flouted Soviet cultural conventions. In fact, he was the victim yet again of state antisemitism.

The Soviet Union had severed diplomatic relations with Israel during the 1967 Six Day War, and Soviet Jews were adversely affected by Moscow’s pro-Arab stance. As Mostovoy, the narrator of The Red Scarf, says, “Jews were subjected to a policy of ‘don’t promote, don’t hire.'”

After four years of apparent joblessness, he finally landed a job on a movie, but midway through it, he was summoned to Communist Party headquarters and accused of conspiring to make a “Zionist” film. The powers-that-be ordered him to delete all the scenes in which a Jewish character appeared.

Several years later, an apparatchik at the Ministry of Cinematography removed his privilege to travel abroad.

With the advent of perestroika in the mid-1980s, a tide of liberalism swept over the Soviet Union, and Mostovoy acquired a good position in the movie industry.

He and his wife immigrated to Israel in 1993, a decision he leaves unexplained, but which was probably motivated by his desire to live in a free country that accepts him on his own merits. Since then, as a freelancer, he has directed a succession of films.