Harry Frank Guggenheim was an American capitalist titan who guided his immensely wealthy family into modernity. He was also a visionary who foresaw that aviation would be fundamental to the transportation infrastructure of the United States and a financial backer of the father of modern rocketry, Robert Goddard.

In addition, he was instrumental in the building of one of the finest art museums in the country and the cofounder, along with his wife, of Newsday, the nation’s most successful suburban newspaper.

He was also, albeit briefly, the ambassador to Cuba when it was little more than an American protectorate.

Dirk Smillie, a former Forbes magazine reporter and a Guggenheim Partners employee, has written an engaging and sympathetic biography of him. The Business of Tomorrow: The Visionary Life of Harry Guggenheim — From Aviation and Rocketry to the Creation of an Art Dynasty (Pegasus Books) takes a reader from his birth in 1890 to his death in 1971.

When he was born, the Guggenheims were already fabulously rich and known as the American Rothschilds. With copper mines and smelters in Mexico, nitrate fields in Chile, tin, gold and diamond mines in Bolivia, Alaska and Africa, and rubber plantations in the Congo, they were wealthy beyond belief.

Originally from a small town in Switzerland, the Guggenheims immigrated to the United States in 1848. The first member of the clan to set foot in the new world, Simon, sold household “notions” — spices, stove polish and embroidery — door-to-door with his son Meyer. After investing in two silver mines in Colorado, Simon decided the future lay in copper, a mineral in high demand as the electrical age dawned. By the early 20th century, the Guggenheims had cornered the copper and silver markets, which generated the kind of wealth that placed them along side the Rockefellers, Fords, Astors and Vanderbilts.

Harry, the son of Daniel, was born in New York City and was delivered by Dr. Simon Baruch, a former Confederate surgeon and the father of the financier Bernard Baruch, who would become one of the Guggenheims’ partners.

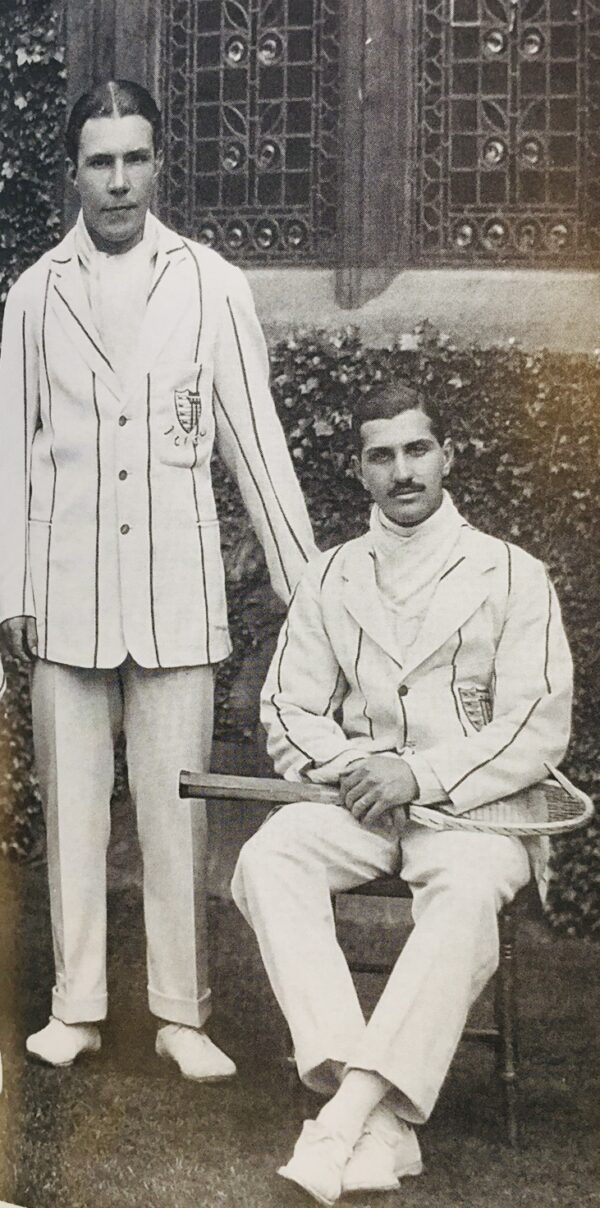

Harry studied chemistry and politics at Cambridge University’s Pembroke College, graduating with average grades. Harry, his father’s successor, learned the mining business from scratch. As Smillie says, “He could hold a chunk of clay slate in his hand and guess the proportion of its copper, silver, lead or zinc.” He also acquired the analytical skills to manage big budgets, big egos and complicated accounting.

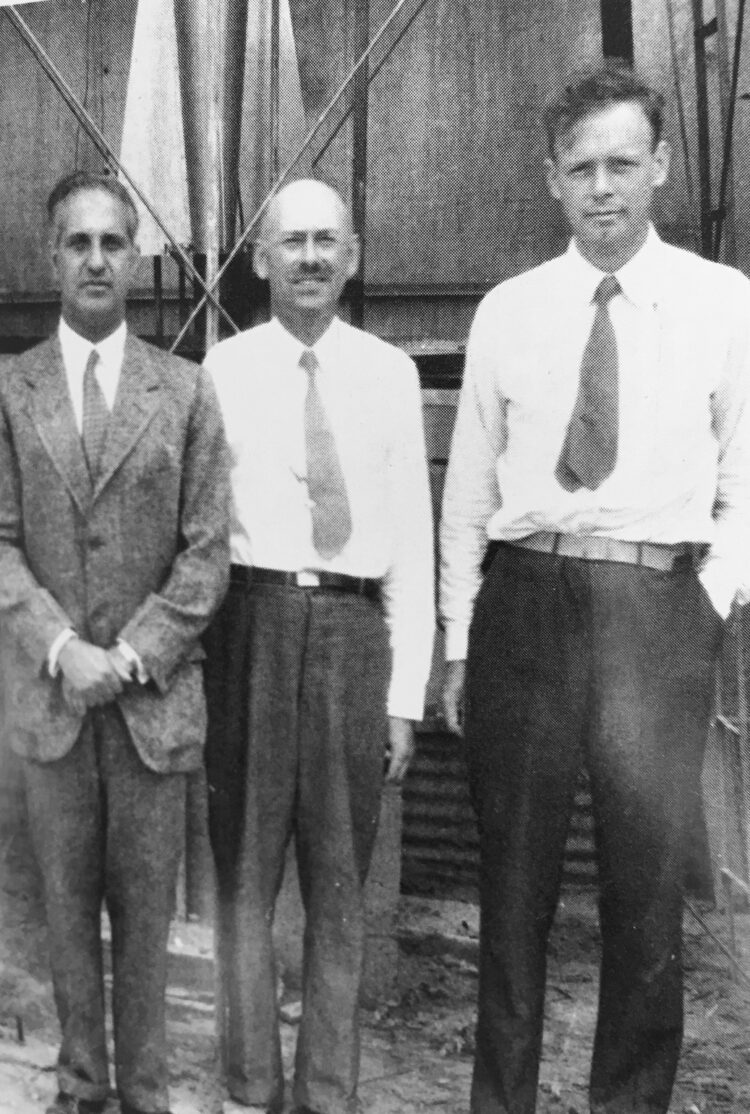

Learning how to fly in 1917, he joined the U.S. Naval Reserve Force, where he gained enormous practical knowledge about aviation. Harry was convinced that aviation was the business of the future, but most Americans regarded flying as dangerous and foolhardy. Undeterred by the mood of the country, he created a fund to promote aeronautics.

In 1927, he was approached by several pilots seeking financing for an attempt to fly nonstop from New York to Paris. Harry rebuffed them, assuming that a solo flight across the Atlantic Ocean would be far too dangerous.

Charles Lindbergh proved him wrong, flying across the Atlantic in the Spirit of St. Louis. Harry regarded his flight as a transformative moment in aviation and arranged a nation-wide tour for Lindbergh. It would reinforce the idea that airplanes could arrive and depart with the precision of a train or the safety of a car. From that moment onward, Harry formed an enduring friendship with Lindbergh.

Harry’s tenure as American ambassador to Cuba was relatively short-lived. He took his job with the utmost seriousness, hiring experts to brief him on the state of the Cuban economy, which was almost entirely dependent on the sugarcane crop. In Smillie’s estimation, Harry’s plan to reconstruct Cuba’s economy and turn the island into a Latin American aviation hub failed.

With Daniel’s death in 1930, Harry became the family patriarch. He would help transform its business, Guggenheim Partners, into a global financial services firm. Yet he allotted time for charitable work, funding settlements in the Philippines and Palestine’s Huleh Valley to resettle Jewish refugees fleeing persecution in Nazi Germany.

Harry reacted with some trepidation to Lindbergh’s visit to Germany in the mid-1930s. But in a letter to Lindbergh, he wrote he had “every confidence” he would give no aid to antisemitism.” Harry acknowledged that Germany had left a positive impression on Lindbergh, but he insisted he was not antisemitic.

Lindbergh and his wife visited Germany again just weeks after the 1938 Munich conference. Two months later, pogroms erupted throughout Germany. Asked for his reaction, Lindbergh said, “They have undoubtedly had a difficult Jewish problem, but why is it necessary to handle it so unreasonably?”

Lindbergh, an isolationist, was a leading member of America First, an organization that urged the United States to adopt a policy of neutrality in foreign affairs and support Germany as a bulwark against the Soviet Union. Harry, an anglophile and a moderate Republican, deeply disagreed with Lindbergh’s position. But like Lindbergh, he believed that communism was the greatest threat to democracy. They also shared the belief that President Franklin Roosevelt had done very little to build a strong American air force.

Harry was profoundly disappointed by a speech Lindbergh delivered in Des Moines, Iowa, in 1941 on behalf of America First. In his speech, he blamed Britain, the Roosevelt administration and American Jews for pushing the United States toward war in Europe.

“I can understand why the Jewish people wish to overthrow the Nazis,” he said. “The persecution they have suffered in Germany would be sufficient to make bitter enemies of any race. No person with a sense of the dignity of mankind condones the persecution of the Jewish race in Germany. Certainly, I and my friends do not. But though I sympathize with the Jews, let me add a word of warning.”

Lindbergh went on to say that Jewish organizations in the United States should not agitate for war, and that the “greatest danger” facing the country was the “large Jewish ownership and influence in our motion pictures, our press, our radio, and our government.”

Harry was distressed by Lindbergh’s antisemitic remarks, claiming he had been influenced by America First extremists.

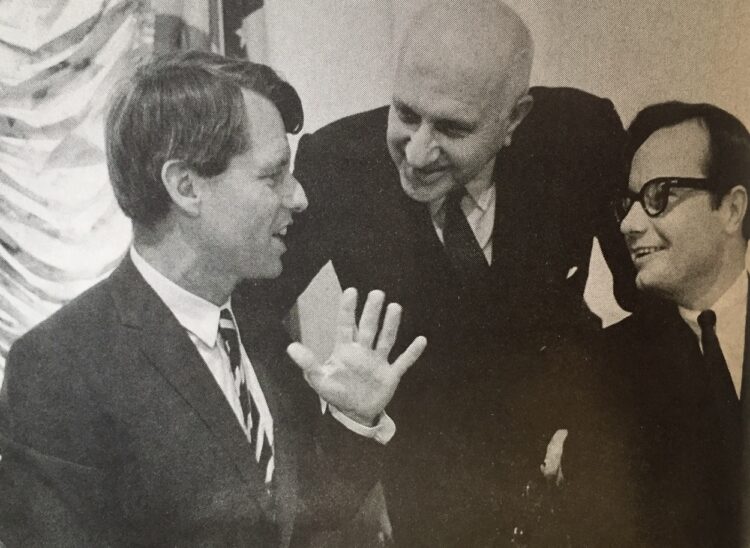

Two years prior to Lindbergh’s speech, Harry met Alicia Patterson, who would be his third wife. She was the daughter of Joseph Medill Patterson, the founder of The New York Daily News. Harry helped Alicia buy Newsday, which would become the most profitable newspaper in the United States. Its circulation reached 425,000 in 1968. Despite Harry’s Republican leanings, he seems not to have objected to its progressive editorial line.

As well, Harry poured his heart and soul into the art museum in Manhattan that bears his family name. The building in which it was housed was designed by renowned architect Frank Lloyd Wright.

Harry’s other passion was thoroughbred horse racing. No surprise here. Horses were a family tradition, says Smillie. Over the course of 35 years, Guggenheim horses won about 1,000 races and appeared in five Kentucky Derbys.

Harry suffered a third major stroke in 1970. It left him unable to speak and barely able to move. He died five months later at the age of 80.

In Smillie’s estimation, Harry played an outsized role in the development of aviation and Goddard’s rocket propulsion research. “Harry felt an obligation, even a duty, to improve the society that made their wealth possible in the first place.”

As he himself said, “I believe there is a responsibility to use inherited wealth for the progress of man and not for mere self-gratification.”