Rudolf Vrba and Alfred Wetzler were the first known Jewish inmates to escape from the Auschwitz-Birkenau extermination camp in Poland, where 1.1 million Jews perished. They escaped in April 1944, nearly one year before the end of World War II. The vital information they conveyed to Jewish communities and Allied powers was timely and explosive.

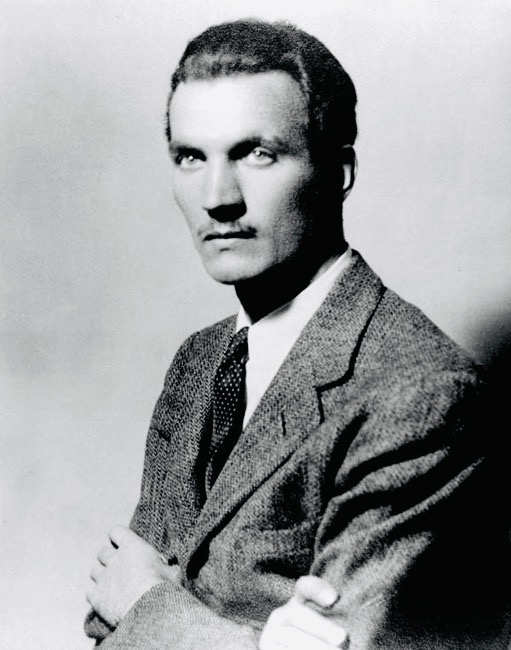

Their astonishing breakout is expertly recounted by Jonathan Freedland in an absorbing and thoroughly researched book, The Escape Artist, published by HarperCollins.

“I came to realize that this is a story of how human beings can be pushed to the outer limits, and yet still somehow endure; how those who have witnessed so much death can nevertheless retain their capacity, their lust, for life; and how the actions of (two individuals) can bend the arc of history,” he writes an an author’s note.

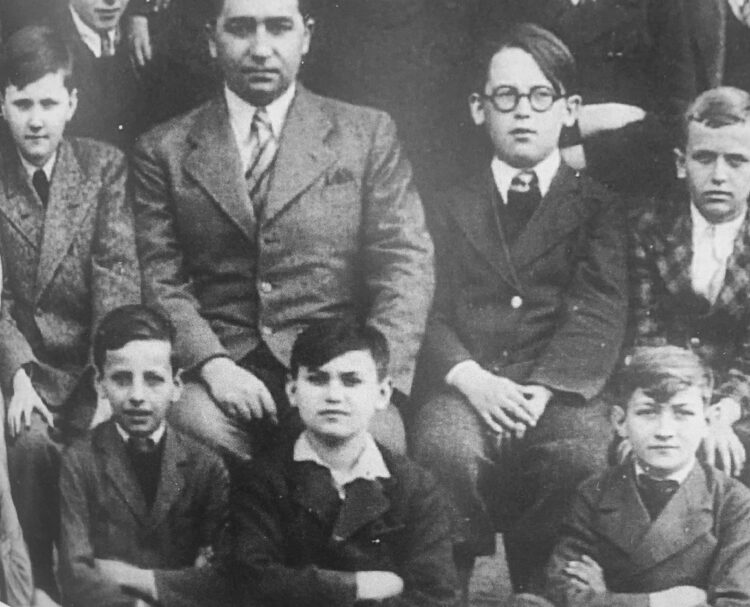

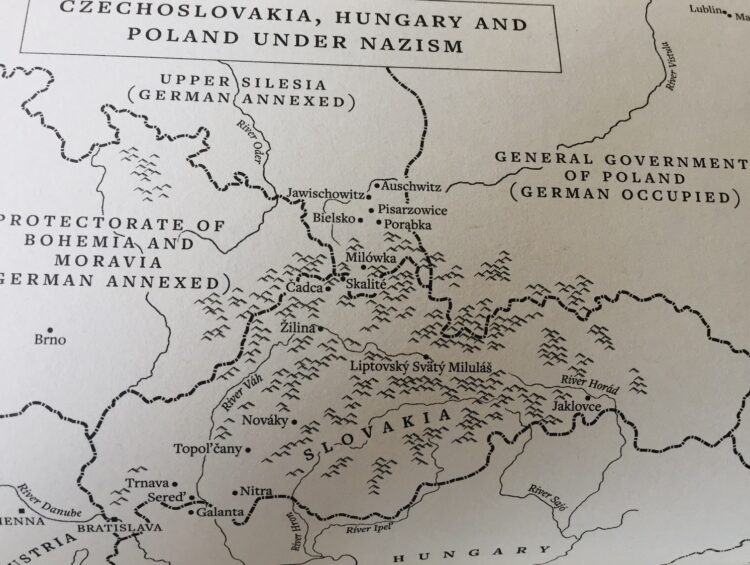

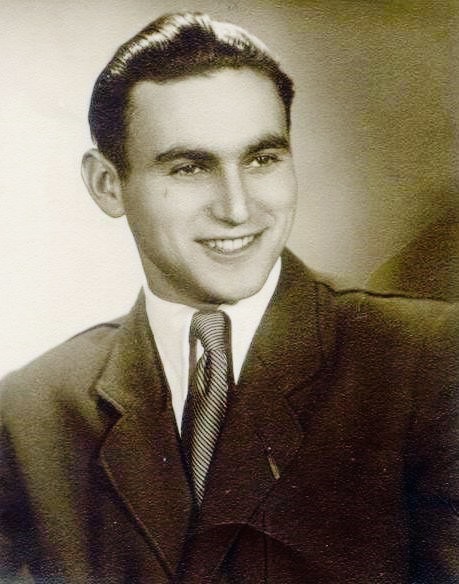

Freedland, a British journalist, focuses on Vrba, whose birth name was Walter Rosenberg. Born in the western Slovakian town of Topol’cany in 1924, he was the son of a sawmill owner.

Jews like the Rosenbergs were subjected to a long list of antisemitic restrictions after Slovakia declared independence from Czechoslovakia in the spring of 1939.

The pro-German fascist republic, ruled by a Catholic priest named Jozef Tiso, banned Jews from government jobs, expelled Jewish students from schools, and introduced its own version of the Nuremberg laws.

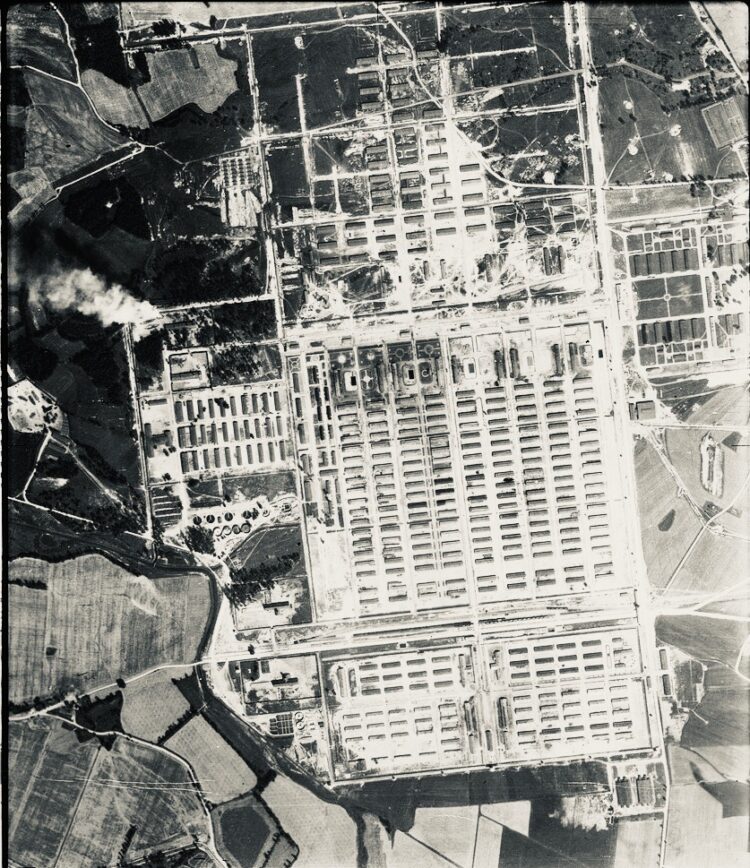

In the summer of 1942, Rosenberg became one of 13,000 Slovak Jewish men to be deported as slave laborers to the Majdanek concentration camp. Toward the end of June in that year, he was transported to Auschwitz, which had evolved from a camp housing Polish political prisoners to a place of mass murder in line with Germany’s genocidal plan to kill the Jews of Europe.

On his first day, he and a team of prisoners were ordered to load corpses on to wagons. Put to work in an SS food store, he was soon transferred to Buna, a network of factories adjacent to the main camp, and then to Kanada, a vast warehouse containing the belongings of new arrivals. Named after Canada, a country of untold wealth, Kanada was piled high with suitcases, clothes, shoes, jewelry, gold and food.

“He had to deduce, as a matter of logic, that Kanada flowed with milk and honey only because those who had brought such delights there had been murdered.”

The goods in Kanada were distributed free of charge to needy people in Germany and to Germans whose homes had been destroyed or damaged in Allied bombing raids.

In the last ten months of his incarceration in Auschwitz, Rosenberg worked on an unloading ramp, removing the luggage of some 300,000 doomed Jews who had arrived in about 300 trains. For out of five of them were selected for immediate death in the gas chamber.

“It did not take long for him to realize what he had to do. If the Nazi plot to destroy the Jews relied on keeping the intended victims entirely ignorant of their fate, then the first step towards thwarting that murderous ambition was to shatter the ignorance … It was the only way to stop the killing. Somebody had to escape and sound the alarm, issuing the warning that Auscwhitz meant death.”

He decided that person would be him.

Having acquired an extensive knowledge of Auschwitz, he knew its precise layout. Rosenberg, too, had witnessed the selection process that preceded the murder of hundreds of thousands of Jews. All this he had committed to memory. He also had discovered that the Germans were preparing to exterminate the Jews from Hungary, whose large Jewish community was the last in Nazi-occupied Europe to be targeted.

What he did not know, of course, was that the United States and Britain, among other countries, had already been privy to first-hand information about the Holocaust.

Jan Karski, a Polish member of the Home Army who had secretly visited the Warsaw ghetto, had informed U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt of the Nazi plan to wipe out European Jews. Toward the end of 1942, British Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden read a statement in the House of Commons condemning the “bestial policy of cold-blooded” extermination pursued by Adolf Hitler’s regime. And a few months later, the Vatican learned that millions of Jews had been killed by the Nazis.

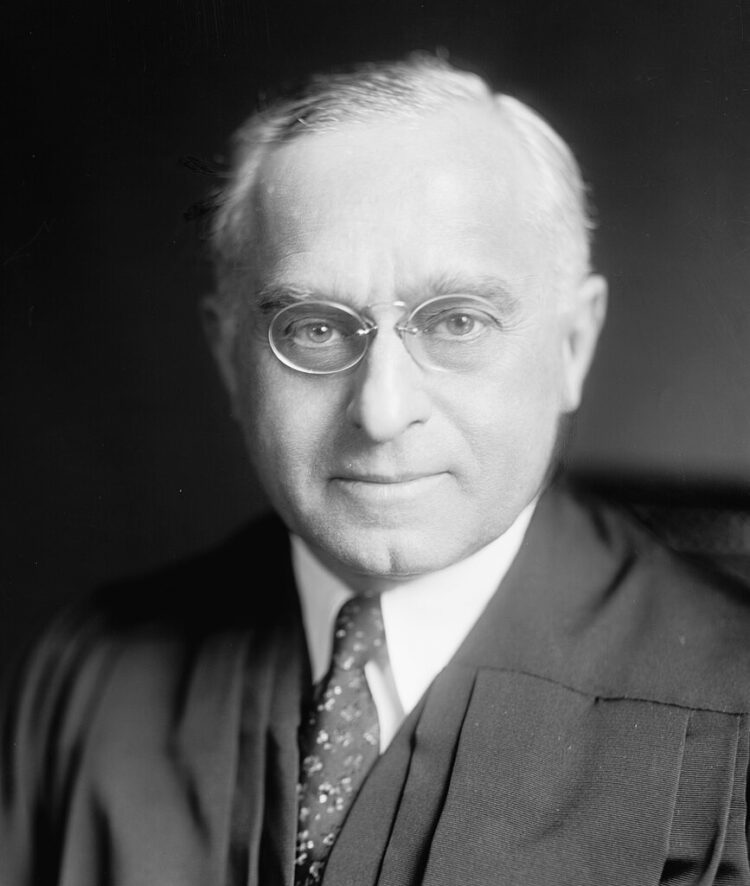

Nonetheless, the sheer magnitude of Nazi crimes was difficult to fathom. After listening to Karski’s chilling account, U.S. Supreme Court judge Felix Frankfurter said, “I do not believe you.” When a diplomat in the room defended Karski’s credibility, Frankfurter added, “I did not say he is lying. I said I don’t believe him. These are different things.”

Rosenberg chose Wetzler — a fellow Slovakian Jew who worked as a registrar in the camp morgue and who was six years older — as his escape partner. “For that role, there could only ever be one person. Someone whom (Rosenberg) trusted wholly and who trusted him, someone whom he had known before he was in this other, darker universe …”

Six hundred Jewish men from their hometown in Slovakia had been deported to Auschwitz in 1942, and only Rosenberg and Wetzler were the sole survivors.

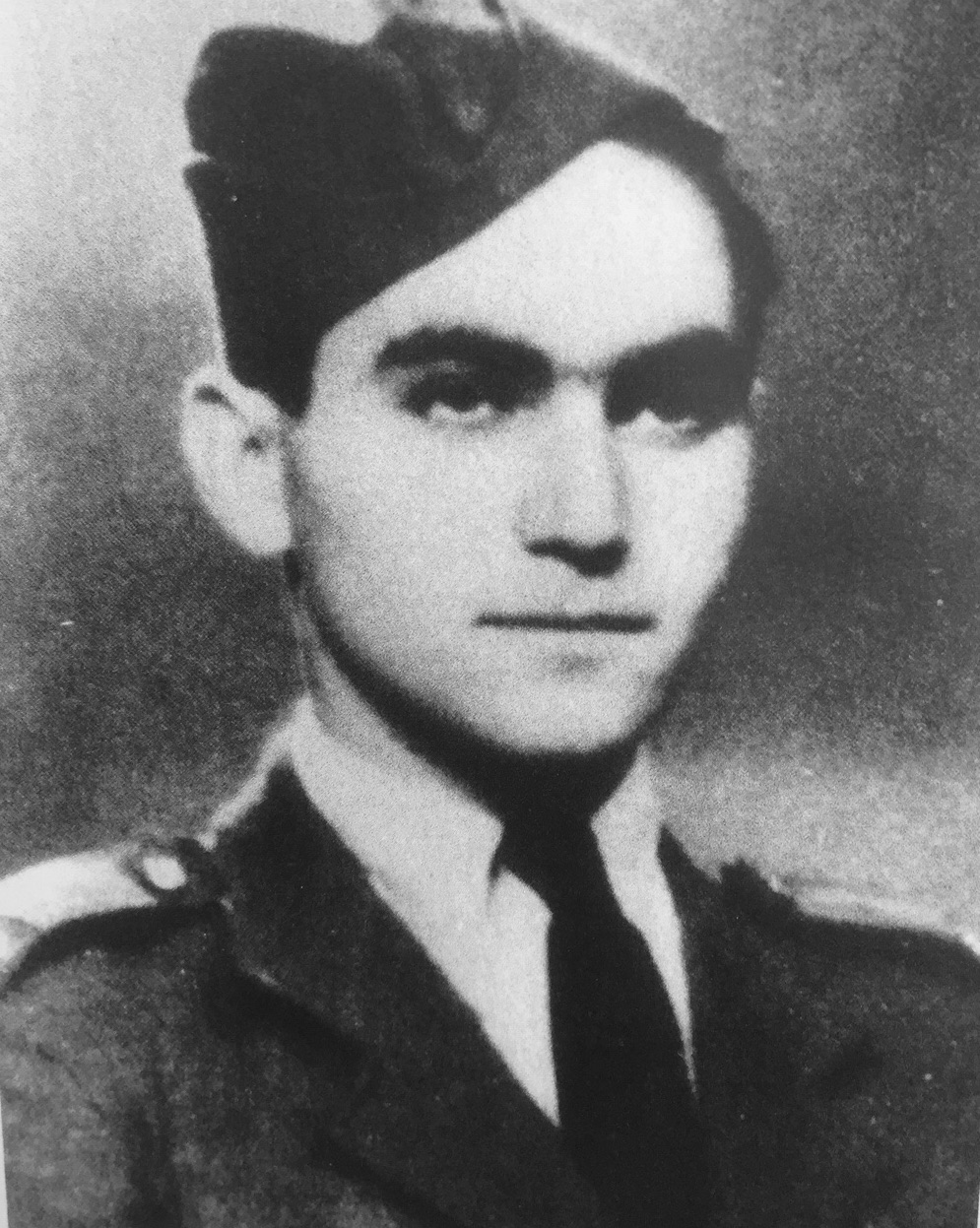

As Freedland observes, some 55 inmates had broken out of Auschwitz before Rosenberg hatched his escape plot. All of them had been Polish political prisoners and Red Army soldiers. Not a single Jew had managed to escape.

Rosenberg’s scheme was remarkably simple yet exceedingly dangerous. They would hide under a woodpile in a pit beneath the planks of an unloading ramp in the outer camp. They had sprinkled the hole in which they would crouch for many hours with Soviet tobacco that had been soaked in petrol to fool SS sniffer dogs. They had learned this trick from a Soviet army officer. They would wait three days and three nights until the Germans had called off the search for them, and then they would climb out of their hiding place and head toward Slovakia, some 65 kilometers away.

The pair escaped on April 10, about a month before the Nazis began to deport Hungarian Jews to Auschwitz. The odds were against them. They were in physically poor condition, their muscles having atrophied after three days of lying still in the pit. They were painfully hungry and desperately thirsty. They had no network of helpers in the countryside to supply them with food, drink and arms. They had no map or compass. The Germans were actively looking for them.

After several days of wandering through a snow-bound dense forest, they came upon a peasant woman. She provided them with breakfast and sent them on their way. Fighting hunger and cold, they eluded a German patrol. Walking by night and resting by day, they met another farm woman, who treated them kindly. By then, Rosenberg’s feet were swollen. A Polish man proved to be of great assistance as well, giving both of them new boots and a package of food.

Once in Slovakia, which Germany had not occupied, they learned from a farmer that a Jewish doctor named Pollack could be found in a small town. He had been spared from deportation because there was a desperate need for doctors in rural areas. Sixty thousand of Pollack’s fellow Slovakian Jews had been deported to Auschwitz between March and October 1942.

Pollack directed them to the Jewish Council in Bratislava, the only Jewish organization the Slovakian fascist regime permitted to function. They contacted one of its members, Oskar Krasnansky, a chemical engineer. He, in turn, introduced them to the council’s president, Oskar Neumann, a lawyer.

In what seemed like interminable interrogations or cross-examinations, Rosenberg and Wetzler revealed their shocking secrets.

The report that the council produced ignored the imminent deportation of Hungarian Jews. “Krasnansky was adamant that the credibility of the report depended on it being a record of the murders that already had taken place. No prophecies, no forecasts, just the facts … Still, Krasnansky (assured) the escapees that what they had revealed about preparations for the mass murder of Hungarian Jewry would be passed on to the relevant authorities.”

At this juncture, Rosenberg and Wetzler were given new identities. Rosenberg was reborn as Rudolf Vrba. By coincidence, a Czech named Vrba had been an antisemitic Catholic priest. Nevertheless, Rosenberg retained this name for the rest of his days. Wetzler was renamed Jozef Lanik.

Their report was transmitted to two Hungarians — Rezso Kasztner, the de facto leader of Hungarian Jews, who suppressed it due to fears of creating panic in the Jewish community, and Geza Soos, an anti-Nazi official in the Foreign Ministry who transmitted it to a high-ranking figure in the Catholic church.

Shortly afterward, two more Jews escaped from Auschwitz — Czeslaw Mordowicz and Arnost Rosin, who confirmed Vrba’s and Wetzler’s revelations.

In the meantime, Hungarian Jews were being transported to Auschwitz. “The Jews of Hungary remained utterly ignorant of their imminent fate. They were boarding trains that would take them to the doors of the crematoria …”

The report reached British journalist Walter Garrett, and he wrote an account of it for the Exchange Telegraph news agency. The first daily newspaper to publish a story on it was the Neue Zurcher Zeitung in Switzerland. The New York Times carried a report in July of that year.

John Pehl, the director of the newly-established War Refugee Board in the United States, decided to publish the report, but the Office of War Information temporarily refused to authorize its publication on the grounds that was unbelievable. Yank, a U.S. army journal, found the report “too Semitic” and requested a “less Jewish account.”

The United States and Britain declined to bomb the rail tracks leading to Auschwitz, even though American aircraft had already bombed a subcamp near it.

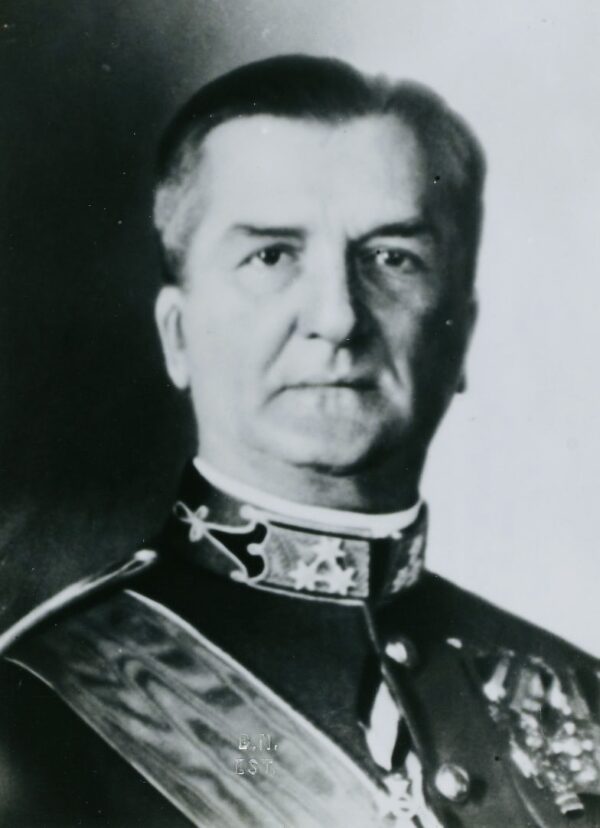

In June, Pope Pius XII sent a telegram to Hungary’s supreme leader, Miklos Horthy, demanding an end to the deportations. The king of Sweden, in a sharply-worded letter, warned Horthy that Hungary risked becoming a “pariah” among nations.

What finally moved Horthy into action was a harsh message from Roosevelt and a U.S. air raid in and around Budapest that killed 136 people and levelled 370 buildings. The deportations were finally stopped, but by then more than 400,000 Hungarian Jews had been murdered in Auschwitz.

However, 200,000 Jews in Budapest, the last remaining Jews of Hungary, were saved thanks to Veba and Wetzler. Some would die a few months later at the hands of fascist Arrow Cross thugs, but the vast majority of Jews they had rescued survived.

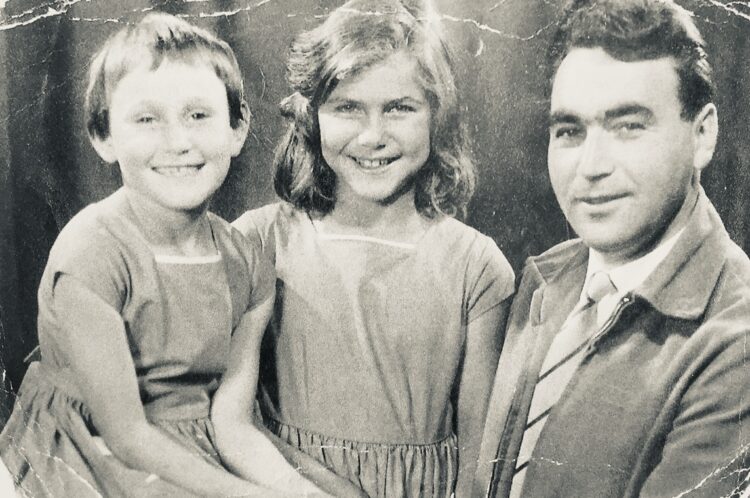

After the war, Vrba joined a partisan band, blowing up German supply lines and artillery posts and railway bridges. Awarded membership in the Slovak Communist Party, he enrolled in the Czech Technical University in Prague, in the department of chemical technology. During his studies, he married a Holocaust survivor, Gerta Sidinova, whom he would ultimately divorce after having two children with her.

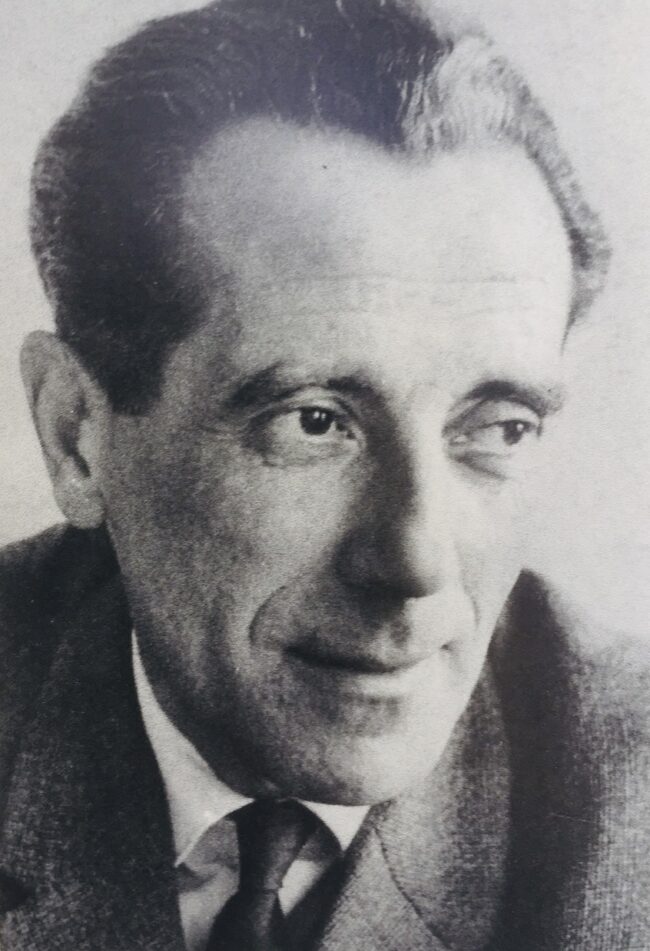

In 1958, Vrba immigrated to Israel, hoping it would be a gateway to the West. He was soon offered a position in the United States, but could not obtain a visa since he had been a member of the Communist Party. He instead took a job at the Ministry of Agriculture. Never a Zionist, Vrba found Israel too clannish and left after eighteen months. He found another position in Britain.

He published his memoirs, I Cannot Forgive, in 1963.

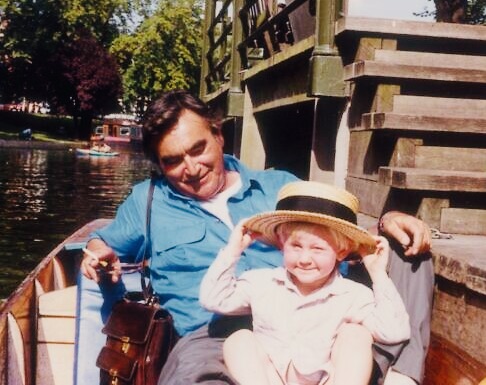

Four years later, he was appointed an associate professor in the faculty of medicine at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver. Shortly after being granted Canadian citizenship in 1973, he landed a two-year lectureship at the Harvard Medical School. He had no trouble getting a U.S. visa. By now, he was a staunch anti-Communist.

Tragedy struck when one of two daughters committed suicide.

During he 1980s and 1990s, he appeared in Claude Lanzmann’s documentary, Shoah, and testified at the trial of Canadian-based Holocaust denier Ernst Zundel. Vrba died in 2006 and was buried in a cemetery in the town of Tsawwassen, on the Canada-U.S. border.

Wetzler, his old friend, passed away in 1988. In his last years, he worked as a librarian in Bratislava.

Freedland, in summarizing Vrba, describes him as the ultimate escape artist.

“He escaped from Auschwitz, from his past, even from his own name. He escaped his home country, his adopted country and the country after that. He escaped, escaped and escaped, but could not break free from the horror he had witnessed and which he had laid bare before the world. His life was defined by what he had endured as a teenager.”

With Auschwitz behind him, he became a scientist, a husband, a father and a grandfather. And thanks to him and Wetzler, tens of thousands of Hungarian Jews survived the Holocaust.