Three years years after the eruption of the third Gaza war, the Gaza Strip remains a tinderbox.

The Gaza region has been fairly quiet since the end of the war, with relatively little cross-border fighting having broken out, but both sides are acutely aware that a fourth round of hostilities could easily flare up again.

By any yardstick, Israel and the Palestinians of the Gaza Strip share a tense frontier.

Although Israel has deterred Hamas, Israel is still plagued by occasional rocket and mortar barrages from Gaza, which has been subjected to an Israeli naval siege for the past 10 years. Israel responds to these attacks by launching limited air and artillery strikes, but from time to time, Israeli counter strikes are more severe.

Despite the violence and the exchange of threats and counter-threats, neither Israel nor Hamas desire a new war.

Israeli Defence Minister Avigdor Liberman has said that Israel has no interest in becoming enmeshed in another armed conflict with Hamas, which represents the rejectionist wing of the Palestinian national movement.

But pointing an accusatory finger at Hamas, Liberman claims that Hamas has invested more than $500 million in rebuilding its military capabilities, while paying relatively little attention to rebuilding Gaza, which was heavily damaged during the last war.

If forced into a fourth war, he warned, Israel will “destroy (Hamas) completely,” a threat that Israel would be hard-pressed to fulfill.

Hamas’ deputy leader, Khalil al-Hayya, has struck a similar tone, saying that Hamas neither wants nor expects a war with Israel.

Despite these disclaimers, Israel and Hamas remain on a war footing.

Israel is constructing a massive underground barrier along its roughly 60-kilometer border with Gaza to ensure that Hamas will be denied the ability to build attack tunnels into Israeli territory.

During the last war, which started on July 8 and ended 51 days later, Israel discovered 14 such tunnels, and 11 of its fallen 68 soldiers were killed in cross-border tunnel attacks. To this day, Hamas holds the bodies of two of these soldiers, Hadar Goldin and Oron Shaul.

Hamas, for its part, is continuing to build tunnels and has reportedly replenished its arsenal of missiles to pre-2014 levels. During the war, which Israel dubbed Operation Protective Edge, Hamas fired some 4,500 rockets and mortars at Israel, many of which were intercepted and destroyed by the Iron Dome anti-missile system.

Politically, Hamas hews to its harsh anti-Israel rhetoric. Although Hamas claims it accepts a two-state solution to defuse the Arab-Israeli dispute, its leaders promote a radical agenda in their incendiary speeches, refusing to renounce violence, recognize Israel’s existence and accept agreements signed by the Palestinian Authority and Israel.

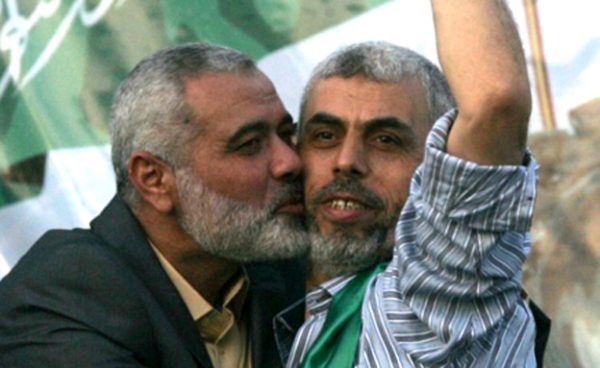

As Hamas commemorated the 13th anniversary of Israel’s assassination of Hamas founder Ahmed Yassin, Yehya Sinwar, who recently succeeded Ismail Haniya as Gaza’s top political official, declared, “Hamas will continue on the path of Yassin for the liberation of all of Palestine. We will not surrender even a morsel of land.”

Mahmoud al-Zahar, the co-founder of Hamas, has been just as emphatic. As he said in May, “If we liberate Palestine … to the 1967 borders, we will go directly to liberate the rest of Palestine and the territories of 1948.”

Zahar’s fiery rhetoric notwithstanding, Hamas is hardly in a position to achieve an objective that has eluded Arab armies since the first Arab-Israeli war nearly 70 years ago.

Currently, Hamas is preoccupied with rebuilding Gaza, parts of which were reduced to rubble by Israel. The international community, and Qatar in particular, have donated hundreds of millions of dollars for reconstruction. But the pace has been slow. By one estimate, one-third of the 160,000 homes that were significantly damaged during the war still lie in ruins.

The only recent ray of light was the inauguration of a Coca-Cola bottling plant, employing 270 workers, last November.

Jobs are scarce in Gaza, with the unemployment rate hovering around the 40% to 50% mark. A power struggle pitting Hamas against its rival, the Palestinian Authority, exacerbates the problem. Hamas seized Gaza in a violent coup in 2007, and the Palestinian Authority, led by President Mahmoud Abbas, has yet to fully come to terms with its loss.

Three months ago, the Palestinian Authority began exerting pressure on Hamas by cutting the salaries of thousands of Palestinians who previously had been on its payroll, but had been paid to stay at home. Earlier this month, the Palestinian Authority sacked 6,000 of these employees, creating yet more hardship in Gaza.

As well, the Palestinian Authority has sharply reduced the flow of electricity to Gaza by reducing its payments to Israel, which supplies much of Gaza’s power. In line with a request from the Palestinian Authority, Israel has gradually slashed Gaza’s electrical supply by one-third.

According to a United Nations report, Gaza requires 400 megawatts of power daily, but is receiving only 40. In practice, this means that electricity is available to the nearly two million inhabitants of Gaza for just four to six hours a day, compared to eight to 12 hours last year. As a result, Gaza is suffering from a serious water shortage and cannot dispose of its waste water, which is flowing into the Mediterranean Sea and preventing Gazans from enjoying the beaches.

Nickoley Mladenov, the UN’s special coordinator for the Middle East Peace Process, has warned Israel that the energy shortage has become a humanitarian crisis that will eventually affect Israel negatively.

In desperation, Hamas has turned to Egypt for relief.

Last month, a high-level Hamas delegation spent more than a week in Cairo in a bid to improve its frayed ties with the Egyptian government. Hamas enjoyed cordial relations with Egyptian President Mohammed Morsi, who had been a top Muslim Brotherhood functionary. But after Morsi was deposed and arrested in a 2013 coup staged by the then defence minister and the current president, Abdul Fattah el-Sisi, Hamas lost favor in Cairo.

In short order, much to Israel’s delight, Egypt began to destroy Hamas’ network of smuggling tunnels running into Israel and the Sinai Peninsula, where an Islamic insurgency has been raging for four years.

With Hamas apparently having agreed to abide by Sisi’s conditions, Egypt sent several million litres of badly needed diesel fuel to Gaza to help run its single power plant. In exchange for these shipments, Hamas made a number of important concessions.

Hamas promised to sever ties with the Muslim Brotherhood, build a closed-off security zone between Gaza and Egypt to prevent smuggling and infiltration, hand over 17 suspects wanted by Egypt on terrorism charges, stop the flow of weapons into the Sinai, and renew ties with Mohammed Dahlan, the Palestinian Authority’s number one official in Gaza prior to 2007.

The fulfillment of these promises may usher in an era of cooperation between Hamas and Egypt, but it’s doubtful whether they’ll change Israel’s poisonous relationship with Hamas.