Assimilated Hungarian Jews were in the forefront of shaping the popular culture of late 19th and early 20th century Budapest, one of the capitals of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and one of the major cities in Europe today. Its edgy nightlife and innovative entertainment industry, encompassing coffee houses, clubs, music halls and theatres, were largely the creation of secular Jews. But the ethos of urban modernity they helped established in Budapest would be stigmatized and maginalized by Hungary’s conservative class.

Appalled by the influence Jews wielded in its “degenerate” and “sinful” capital, antisemites took to branding it Judapest, a contemptuous term coined by the antisemitic mayor of Vienna, Karl Lueger, and tacitly endorsed by Hungary’s post-World War I leader, Miklos Horthy, who would authorize the extermination of more than 400,000 Hungarian Jews during the Holocaust.

Mary Gluck, a professor of history and Judaic studies at Brown University, has written an erudite account of this period, which spanned the years from 1867 to 1914. In The Invisible Jewish Budapest: Metropolitan Culture at the Fin De Siècle (The University of Wisconsin Press), she examines the phenomenon of Jewish modernity through “everyday narratives, informal practices and popular rituals of urban life.” She refers to this bygone world as “invisible” because of its stigmatization by “official culture.”

The era she discusses in such meticulous detail is framed by two major events — the 1867 constitutional union between Austria and Hungary, which gave rise to the Dual Monarchy, and the Emancipation Decree, which was issued in the same year and granted Jews full political and civic equality.

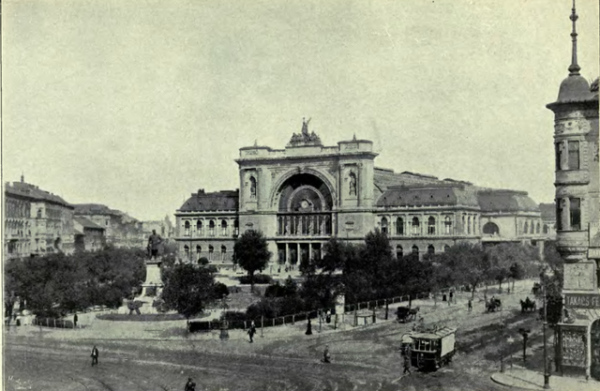

These events coincided with the evolution of Budapest into a sophisticated and cosmopolitan metropolis.

According to Gluck, the monumental renewal projects that transformed Budapest into a world-class city were financed, in part, by Jewish capital. Budapest’s urban culture, in turn, “provided large segments of the Jewish population with new social identities that replaced traditional ethnic and religious affiliations.” The Jews of Budapest, comprising 23 percent of its population by 1900, were drawn to its grand boulevards, aromatic coffee houses, lively music halls and witty cabarets.

The vision of modern Budapest, she observes, was articulated Jozsef Kiss, one of the most celebrated Jewish literary figures of his day, in a seven-volume potboiler, Mysteries of Budapest.

The city’s cultural landscape was minutely described by Henrik Lenkei, a Jewish poet, playwright and educator, in Budapest, The City of Entertainment, one of the most comprehensive guidebooks of the 1890s.

Gluck refers to the coffee house as a space of “sociability and cultural democracy” where novels and poems were written and where artistic doctrines were debated. By 1900, Budapest was home to an astonishing 500 such cafes. To critics, the coffee house was a den of corruption and disreputable behavior.

Jewish humor flourished in music halls like the Folies Caprice, whose most important asset was Sandor Rott, the greatest comic artist of his age, and in the pages of the magazine Borsszem Janko, which was edited by the Polish-born Adolf Agai. Like many Hungarian Jews, he falsely assumed that the convergence of Hungarian nationalism, political liberalism and Jewish emancipation would be to his advantage.

His contemporary, Mor Wahrmann, a wealthy banker and the first Jewish member of Parliament, presented himself as the archetypal assimilated Jew. “His greatest and most frequently cited achievement was his ability to align and harmonize his Jewish and Hungarian identities,” writes Gluck.

Throughout this period, outbursts of antisemitism erupted. Hard-core antisemites in Parliament presented motions to revoke the Emancipation Decree, and a blood libel accusation emerged in the town of Tiszaeszlar. “The appeal of antisemitism was temporarily halted by the combination of government suppression, public fatigue and inner dissension and scandal within the ranks of the antisemitic leadership,” says Gluck.

She adds, “The Hungarian Jewish ideology of assimilation, based on a reinterpretation of Hungarian liberal values, turned out to be far more fragile and fraught with anxiety than its public rhetoric would suggest. Despite its sincere and vehement affirmation of Hungarian patriotism, it could not abolish the Jewish question from Hungarian public life.”

During this period, she adds, “Hungarian liberal dreams of a national middle class, combining the progressive values of the West with the historical traditions of Hungary, did not come to fruition.”

For all intents and purposes, the culture of Jewish Budapest fizzled out with the outbreak of World War I in 1914 and the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in 1918. “Hungarian Jews found themselves transformed into citizens of a truncated ethnically homogeneous state where their status as a religious and cultural minority was increasingly contested.

To say the least.