On May 1, Hamas — the Palestinian Islamic fundamentalist group that has ruled the Gaza Strip since 2007 — released a new document of principles aimed at softening its extremist image and presenting itself as a pragmatic organization grounded in realism. It was a step in the right direction, but it was only a baby step and, for all intents and purposes, Hamas is still steadfastly dedicated to its original and overriding objective — Israel’s destruction.

Hamas’ intention was to amend its first national covenant, which was rife with antisemitic and anti-Zionist tropes. But on the face of it, Hamas hardly budged. Its refusal to make a clean break with its past is clear for all to see.

Its 1988 charter, issued some eight months after the eruption of the first Palestinian uprising, reeked of political incalcitrance and anti-Jewish malice. Calling for Israel’s obliteration, it curtly dismissed the possibility of a negotiated settlement with Israel and boldly decreed that “the liberation of Palestine is a personal duty of every Palestinian.” It also referred menacingly to Jewish influence and power in the world and validated the despicable canards in The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, an early 20th century czarist forgery that intensified antisemitism in Europe and elsewhere.

During the second intifada, which broke out in 2000, Hamas initiated a concerted campaign of violence in Israel, killing hundreds of Israelis in a spate of suicide attacks. In the wake of Israel’s unilateral withdrawal from Gaza in 2005, the Palestinians could have focused their efforts on bringing a measure of prosperity to Gaza. Instead, Hamas continued to build up its military arsenal and fire rockets and mortars at Israeli towns, kibbutzim and moshavim near the border.

In 2006, Hamas defeated Fatah in the general election. A year later, Hamas staged a bloody coup, ousting representatives of the Palestinian Authority from Gaza. By doing do, Hamas split the Palestinians into two opposing camps. From that point forward, Hamas administered Gaza while the Palestinian Authority governed the West Bank, a schism that has yet to be healed.

Rising tensions between Israel and Hamas resulted in the eruption of wars in 2008, 2012 and 2014. Since the last outbreak of fighting nearly three years ago, there have been relatively few border incidents, but Hamas has rearmed itself and continues to build attack and smuggling tunnels.

Last month, Khalil al-Hayya, Hamas’ deputy leader, claimed it does not seek another war with Israel and remains committed to the ceasefire brokered by Egypt. But Hayya blamed Israel for the recent assassination of one of its chief operatives, Mazen Faqha, who was gunned down under mysterious circumstances.

Hamas’ policy of defiance and hostility toward Israel has not eased material conditions in Gaza, which suffers from chronic high unemployment and acute power shortages.

Although Hamas is a champion of Palestinian unity, its relationship with the Palestinian Authority is strained by policy differences. Late last month, the Palestinian Authority announced it would no longer pay for the electricity that Israel supplies to Gaza.

Hamas’ ties with Egypt are also problematic, with Cairo having accused it of aiding Islamic radicals in the Sinai Peninsula and the Egyptian mainland.

Last but not least, Hamas is widely regarded as a terrorist organization by several of the major powers, including the United States.

As a result of its growing isolation, Hamas was under increasing pressure to strike a conciliatory tone. In a reference to yesterday’s statement of principles, Hamas spokesman Fawzi Barhoum said, “This document gives us a chance to connect with the outside world. Hamas is not radical. We are a pragmatic and civilized movement.”

Hamas’ updated covenant was unveiled by Khaled Mashaal, its outgoing leader, in Doha, the capital of Qatar, only two days before Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas was due to meet U.S. President Donald Trump at the White House in Washington, D.C.

In Mashaal’s estimation, the new manifesto reflects a “reasonable” Hamas that is “serious about dealing with the reality and the regional and international surroundings, while still representing the cause of its people.”

This is an exaggeration, to say the least. The changes that were announced are basically cosmetic in nature.

Hamas removed or diluted negative references to Jews. “Hamas does not have a conflict with the Jews because they are Jews, but Hamas has a conflict with the Zionists, occupiers and aggressors,” the document states.

Hamas, while ready to endorse the formation of a provisional Palestinian state in the West Bank and Gaza, rejects Israel’s existence. Nor is Hamas prepared to recognize Israel and drop future claims against Israel.

Further, Hamas holds that Palestinians have the right to return to their former homes and properties in Israel.

And Hamas has not renounced terrorism. As the document says, “Hamas refuses to hinder the resistance of its weapons.”

Hamas’ refusal to come to terms with Israel’s legitimacy is glaring, though hardly surprising.

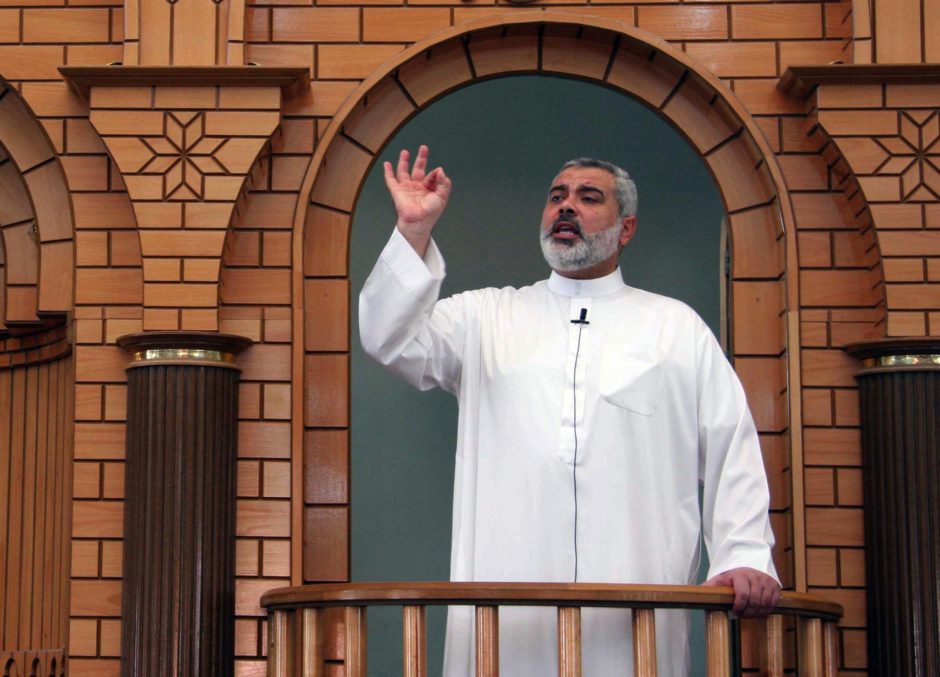

Its new leader in Gaza, Yahya Sinwar, enunciated this cardinal principle in a speech in March. Speaking at an event marking the 13th anniversary of the Israeli assassination of Hamas founder Ahmed Yassin, Sinwar declared, “Hamas will continue in the path of Yassin for the liberation of all of Palestine.”

Sinwar’s colleague, Mahmoud al-Zahar, a senior Hamas official, delivered a similar message when he said, “We have liberated Gaza, part of Palestine, but I am not prepared to accept just Gaza. Our position is: Palestine in its entirety, and not a grain of soil less. Allah did not define the 1967 or the 1948 borders. We will fight (Israel) wherever we can — on the ground, underground, and if we have airplanes, we will fight them from the skies.”

In the new document, Hamas distances itself from the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt, in the hope of appeasing Egyptian President Abdel Fatah el-Sisi. After ousting Mohammed Morsi, Egypt’s first democratically-elected president, Sisi cracked down hard on the Muslim Brotherhood, banning it and arresting thousands of its members.

Of late, Egypt’s intelligence service has renewed its ties with Hamas, hoping that a rapprochement will contribute to the battle against the Islamic State affiliate in the Sinai Peninsula, Sinai Province, and enhance its status as a mediator in Israel’s conflict with the Palestinians.

Last week, Sisi urged Trump to restart talks between Israel and the Palestinian Authority.