David Stoliar, the sole survivor of a shipwreck which graphically symbolized the world’s indifference to Jewish suffering during the Holocaust, has died. Stoliar, The New York Times reported on January 23, passed away in Bend, Oregon, on May 1, 2014. He was 91.

I interviewed Stoliar in connection with the release of The Struma, a 2001 documentary written and directed by the Canadian filmmaker Simcha Jacobovici.

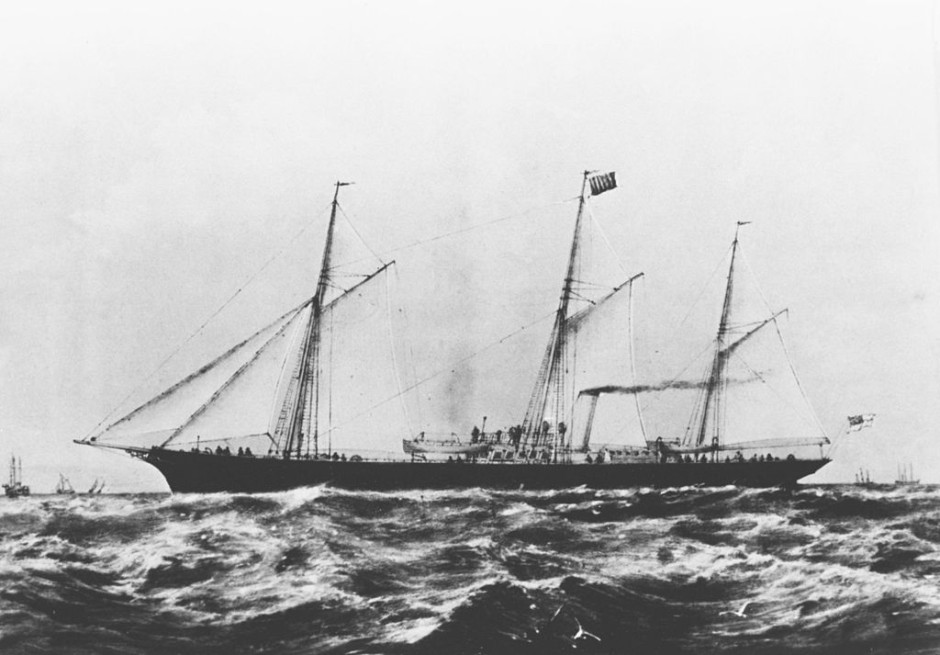

The Struma, built as a yacht in 1867 and subsequently converted into a cattle boat, was sunk in the Black Sea by a Soviet submarine in the winter of 1942. It was carrying 779 Jewish refugees and a crew of 10 when disaster struck.

For decades, Stoliar remained silent about the incident, the worst maritime catastrophe of World War II. But after a British diver organized a search for the vessel in 2000, a project that prompted Jacobovici to make his film, Stoliar began talking to the press. I was one of the journalists who was granted a phone interview with him. By then, he resided in Bend with his second wife, Marda.

Stoliar was born in Kishinev, Romania, on October 31, 1922. When he was 10, his parents, Jacob and Bella, divorced. He joined his mother in Paris and returned to Romania in 1936.

Antisemitism in Romania had always loomed large. But after the outbreak of the war, the situation turned increasingly precarious for Jews. In 1940, under pressure from Germany and the Iron Guard — a pro-German fascist political movement — the Romanian regime disenfranchised Jews, rescinding their citizenship.

Shortly afterward, Ion Antonescu, a former army general and defence minister, formed a new government in league with the antisemitic Iron Guard. Repercussions followed. Jewish shops and Jewish-owned companies were confiscated. Jewish homes were looted and synagogues were destroyed. Jews were pressed into labor battalions. In Bucharest, the capital, the Iron Guard killed 120 Jews in a massacre.

On June 29, 1941, the Jews of Jassy were subjected to a pogrom perpetrated by the German and Romanian armies in conjunction with the Einsatzgruppen, a Nazi mobile killing squad. As German and Romanian soldiers rolled through Bessarabia, Bukovina and Dorohoi, they slaughtered yet more Jews.

Toward the close of that terrible summer, the Romanians sent Jewish deportees to Transnistria, where tens of thousands perished.

Like all able-bodied young Jewish males, Stoliar was dispatched to a forced labor camp. When he was released, his father, a textile manufacturer, decided to send him to Palestine.

“Life as a Jew in Romania had become extremely difficult, dangerous and unbearable,” he said.

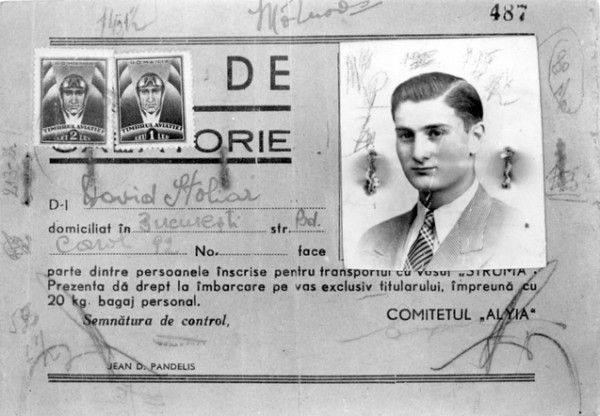

Passengers paid up to $1,000 for a place on the Struma, which was less than seaworthy. Before boarding the vessel in Constanza on December 12, 1941, they were harassed by Romanian customs officials, who stole their money and jewelry.

Stoliar boarded the Struma along with his fiancee, Ilse Lothringer, and her family. He was shocked by the appalling conditions and the scarcity of toilets. He wanted to get off, but “there was no way back.”

Palestine, in 1941, was ruled by Britain under a League of Nations mandate. Stoliar was not a Zionist, but that didn’t matter. “I did not care about politics at that time,” he said. “Survival was my priority.

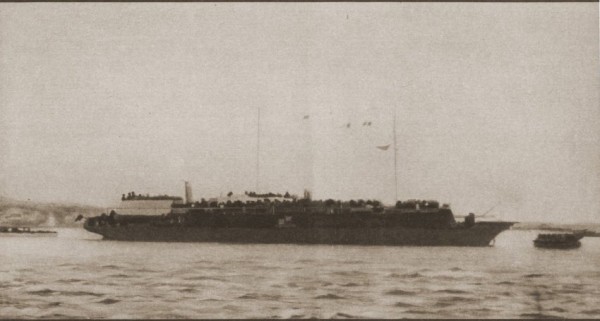

Within an hour of leaving Constanza, the ship’s engine broke down. The captain of a passing tugboat demanded a reward — the passengers’ wedding rings — to repair it. A few days later, the engine failed again. Turkish tugboats towed the Struma into the Bosporus, the body of water dividing Europe from Asia, and then into Istanbul harbor. There it languished for weeks under quarantine.

The Struma, designed for 150 passengers, was in terrible condition, Stoliar recalled. “The air inside was stifling. The stench was retching. We took turns on the deck. No one could bathe. Access to the toilets was very limited. There was a shortage of food and fights over it. We had over 30 doctors on the ship, but no medicine, not even aspirin. The ship was a filthy, floating coffin.”

He added, “We knew we would never make it to Palestine. Our only hope was that the Turkish authorities would allow us to leave the ship.”

Turkey permitted the Jewish community to send food and supplies, but allowed only 10 passengers to disembark.

A neutral power until the tail end of the war, Turkey was caught between a rock and a hard place. Turkey had no desire to antagonize Germany, whose troops were stationed in Bulgaria, perilously close to the Turkish border. Nor did Turkey wish to upset Britain, which had imposed restrictions on Jewish immigration to Palestine.

The plight of the passengers on the Struma was paradigmatic, underscoring the virtual abandonment and powerlessness of European Jews during the Holocaust.

Due to these pressures, Turkey callously washed its hands of the Struma. It was towed back to the Black Sea and set adrift without even a functioning engine.

The following day, on February 24, 1942, a Soviet submarine fired a torpedo toward the Struma. Its commander was under orders to sink neutral ships in the Black Sea to prevent goods from reaching Germany.

The sinking took place less than a month after the infamous Wannsee conference in Berlin, which decreed that the Jews of Europe should be systematically annihilated.

The force of the blast from the torpedo hurled about 100 people, including Stoliar, into the depths of the cold sea. “When I surfaced, the ship was gone,” he recalled. “We all tried to hold on to debris and keep afloat. By evening, the other people swimming in the water had drowned. I saw the chief mate, Lazar Dikof, clutching a fragment of a door, but he died of exposure.”

Stoliar was unscathed by the explosion, but frostbite affected his hands and legs. To his joy and amazement, a Turkish coast guard cutter rescued him. Stoliar was taken to the fishing village of Sile, where he rested for two or three days. Then, after a week of treatment at a military hospital, he was jailed for six weeks.

With the help of Istanbul’s Jewish community, Stoliar received an entry certificate to Palestine from the British consulate. A friend who lived in Palestine took him under his wing. Stoliar joined the British army in 1943 and was posted to Egypt and Libya.

After the war, Stoliar returned to Palestine with his new Egyptian wife, Adria Nacmias, who died in 1961. During the War of Independence, he served in the Israeli army.

Upon demobilization, he worked for an oil company in Haifa. His son, Ron, was born in Israel. In 1954, Stoliar accepted a job in Japan, where he worked for 18 years. Before moving to Bend, he lived in Paris and Taipei.

Stoliar’s father survived the war in Bucharest. “He managed to keep away from problems,” said Stoliar. His mother, rounded up by the Gestapo in Paris, was murdered in Auschwitz-Birkenau.

Stoliar, however, was granted an extended lease on life.