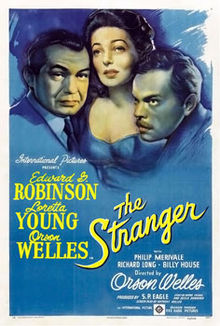

The third movie directed by Orson Welles, The Stranger, is a melodrama about a Nazi who masquerades as a college professor in small-town America. Filmed in the autumn of 1945 and released in the summer of 1946, only a few years after the release of two of his finest films, Citizen Kane and The Magnificent Ambersons, it stars Welles as the German imposter, Loretta Young as his wife and Edward G. Robinson as a war crimes investigator who pursues him.

Now available on the Netflix streaming network, it contains all the elements of a classic film noir — snappy dialogue, mounting tension and intrigue, eerie shadows, revealing closeup and a spine-tingling musical score.

A box-office hit, The Stranger remains unique in one respect. It was the first Hollywood film to present documentary footage of the Holocaust. Welles obtained it from American cinematographers who happened to be in Europe following Nazi Germany’s surrender.

The inimitable Robinson, one of the most successful Jewish actors in the American movie industry during the 1930s and 1940s, plays Wilson, a War Crimes Commission detective who’s determined to ferret out Franz Kindler (Welles). Kindler, a war criminal who goes by the name of Charles Rankin, is said to have conceived the theory of genocide. Somehow or other, he managed to enter the United States and insinuate himself into the placid community of Harper, Connecticut.

A chameleon of the first rank who speaks idiomatic, unaccented English, he has integrated himself so seamlessly that he’s due to marry the daughter of a U.S. Supreme Court judge, Mary Longstreet (Young). As preparations for the forthcoming wedding proceed, Kindler’s former aide, Konrad Meinike (Konstantin Shayne), a former concentration camp commandant, shows up in town and urges him to turn himself in. Enraged by his suggestion, Kindler deals with him harshly.

Wilson, aware of Meinike’s mission, arrives in town and meets the unsuspecting Kindler. During the dinner table conversation, Kindler pretends to be anti-German, but Wilson is on to him, having observed that he described Karl Marx, the political theoretician, as a Jew rather than as a German. Wilson warns Mary’s brother that Rankin is not who he appears to be.

In his quest to convince Mary that her husband is a Nazi fugitive, he screens a clip of a Nazi concentration camp with a gas chamber and tells her of Kindler’s ideological contribution to Nazi mass murder theory. Mary, however, refuses to believe that Kindler/Rankin is a villain. “He’s not a Nazi, he’s not one of those people,” she shouts hysterically.

Undaunted by her naivety, Wilson is bent on exposing and arresting Kindler.

By no means a first-class film, The Stranger is less than plausible for a number of reasons. How could a Nazi of his stature get into the United States just a year after the war without having caused the slightest suspicion? How could his spoken English be so impeccable?

Welles’ performance is substandard. Usually glowering, his character is strictly one-dimensional. And his relationship with Young, who’s hardly convincing herself, is totally bereft of chemistry. Only Robinson projects credibility.

If nothing else, the film is a relic from a bygone era, reflecting Americans’ attitude to Nazi Germany just a year after Germany’s defeat and the liberation of the Auschwitz-Birkenau extermination camp.