Guy Pickering, the former South African Army commander, former agronomist, former rugby player and, of late, the charismatic owner of the lodge where I was staying, exploded into the breakfast room with the news that the birth of a calf was imminent.

“Mia, get up if you want to see this damn thing give birth. She’s been in labor all night.”

His voice sounded like gravel being dragged over a metal surface. I hopped on the back seat of his motorcycle, and off we roared down a dirt road towards the farm.

The calf was upside down, her leg sticking out of the cow. Guy barked orders. “Warm water!” A sloshing bucket of water appeared in front of him as workers scurried away. He reached inside the cow and pulled on her leg. I stood back in wonder as excrement and mucus splattered his arms and legs and amniotic fluid created puddles around his feet.

He reached inside even further and pulled. The calf slid out, as if on a water-slide. She lay on the ground, unmoving. Her mother, exhausted, didn’t move.

Ross, Guy’s new farmhand, lifted the calf up and placed her in front of the mother’s face. The mother lavished her tongue over her. The calf was audibly breathing now. The cow sprang up, more fluid pouring out of her, and moved in front of her new charge, attempting to head-butt Ross.

The calf’s brush with death was a reminder of the ever-present shadow of mortality in Malawi, one of the poorest countries in Africa.

I was in Malawi to visit a school a group of us had started years earlier in Kachere Juvenile Prison. By default, our foundation, I Live Here, is the only non-governmental organization in Malawi to be doing this kind of work. The project began shortly after September 11, 2001, which changed the compass of my life. After these events, I wanted to understand more about the origins of violence and its relationship to poverty.

So, working together with a group of international artists from all over the world, I decided to put together an anthology about human rights abuses all over the world.

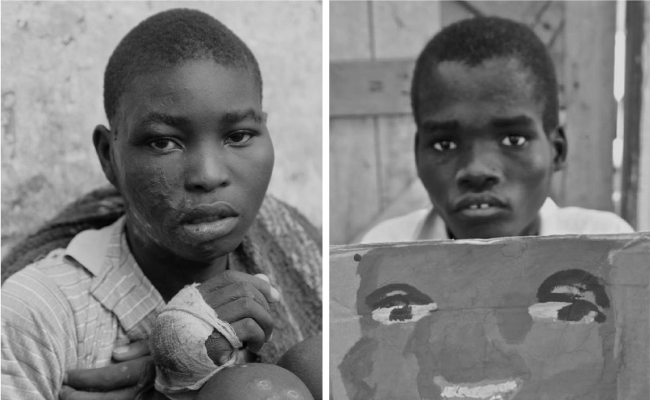

Malawi was the last country I visited in collecting material for my book. I arrived in Kachere Prison in 2006 and was deeply affected by the way the boys here lived and their touching humanity in the face of abhorrent conditions. Most of them were in prison due to staggering poverty. Many sat in remand for years. The prison looked like an abandoned refugee camp, and the odor of urine, excrement and cooking smoke stung my eyes shut.

Pantheon published I Live Here in 2009, but the memory of the prison lingered on. I decided to start a school, not knowing what lay ahead. The following September, we started a humble new school. Now, thanks to the dedication of my colleague, Erica Solomon, our teachers, Ingrid Jeunehomme and Qamile Kosumi, and the Royal Norwegian Embassy, the school is a going concern.

Life in this prison, however, is hard on its inmates. Last year, a boy died in one of the cells because, as one of the officers admitted, there was no money to call a doctor.

A metal door separates the cellblocks from the school in Kachere our foundation established. The school, which now has 210 pupils, is basic. We have three tidy classrooms, three bathrooms and one teacher’s staff room

We are opening two more schools in the future. One, in Maula, is in a prison for women, and another one is in a newly built girls’ reformatory in Muzuzu.

Opening up the school in Maula was never part of our plan. In 2006, officers had told me that women in Maula were allowed to attend a school in the men’s section that houses over 2,000 prisoners. This school is run by a Canadian, Fr. Dennis Hamlin.

The women in Maula had never attended school because they were not allowed to associate with the male prisoners. After I suggested that an education would be beneficial for them, the officer in charge at Maula Prison welcomed the idea, saying he would be happy to have us run a school. I didn’t expect the conversation to be this simple and direct. He said that women had been complaining.

Days later, I was beside myself with excitement, eager to convey the news to the women. The officers called the women to gather round. Half of the women came to the meeting. The rest slept in the sun or remained in their rooms. Nonetheless, I was happy.

Through an interpreter, a fellow inmate, I said, “I’m proud to announce that we have been given permission to run a fulltime school in Maula.” A stillness settled over the room as the women looked at me, scowls on their faces. “You will now have equal access to education,” I added.

The silence was finally broken when a woman clapped, but I wondered whether I would be received as one of those white people who flit in and out to provide aid.

My translator said: “These women have either never been to school, or have been forced quit because they’re poor.”

In Malawi, my translator explained, the majority of women do not have access to education. They bear the brunt of the workload at home. They do the manual labor, the cleaning, the cooking and look after their kids. Many come from backgrounds scarred by extreme violence.

I looked around. One of the girls was having her hair braided as her toddler sat on her lap, eating dirt from the ground. Another woman, near me, was pregnant.

This tableau spoke volumes about poverty, gender and opportunity in Malawi. Due to poverty and gender inequality, so many women have been prevented from attending school. Our job now is to level the playing field and give them a good education so that the floodgates of opportunity can be opened.

I believe in these women. I believe in the boys of Kachere. I believe in our work. This is my compass.