The eighty fifth anniversary of Kristallnacht, the Nazi pogrom in Germany that signified a prelude to the Holocaust, was marked yesterday. Anders Ostergaard’s documentary, Winter Journey, a heart-wrenching account of Jewish displacement in Nazi Germany, touches on this castrophic event within the context of a German Jew’s flight from marginalization, torment and persecution in his homeland.

Now available on the ChaiFlicks streaming platform, it revolves around a father and a son, George and Martin Goldsmith, whose reconstructed conversations speak volumes about human resilience in the face of oppression.

Gunther Ludwig Goldschmidt, as he was known in his native Germany, was a musician for whom hope sprang eternal. A German patriot, he remained in Germany even after Kristallnacht, hoping that the Nazi regime would soon crumble.

When he belatedly realized that the Nazis intended to drive Jews out of Germany and exterminate them, he and his wife, Rosemarie, emigrated and settled in the United States, where Martin was born.

An inquisitive fellow, Martin seeks to piece together his family’s history and to ascertain what his parents’ reaction was to the rise of Nazism in Germany. It’s a tall order, since George died in 2009. Martin circumvents this problem through the medium of reenactments and digital magic.

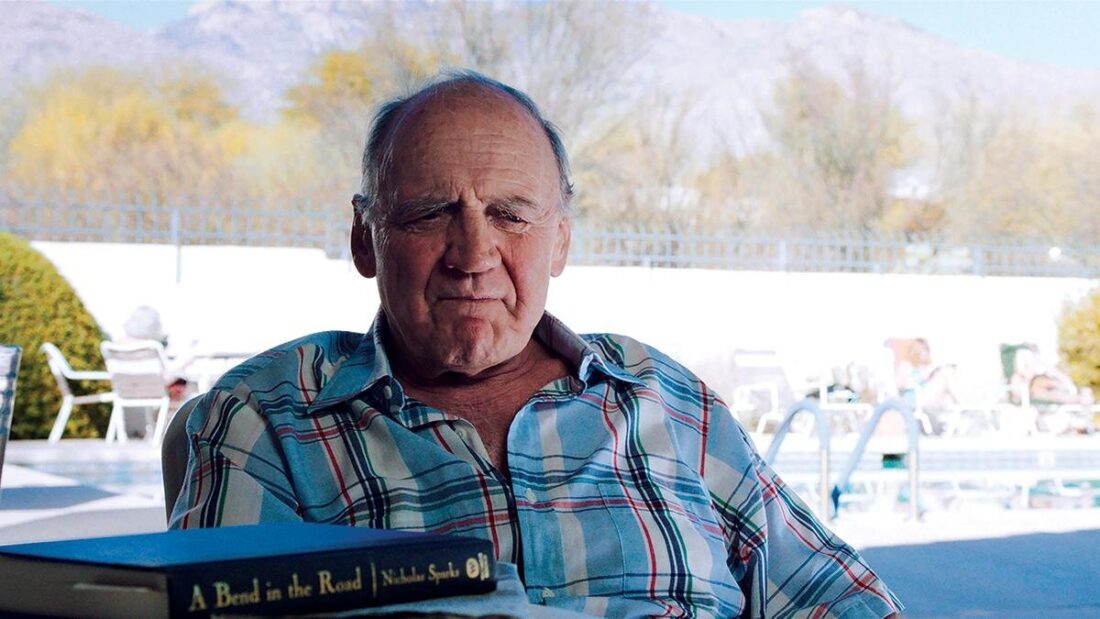

Bruno Ganz, the distinguished German actor who portrayed Adolf Hitler in the feature film Downfall (2004), plays his father in a stunning performance that feels unreservedly real. The black-and-white reenactments, seamlessly blended with archival footage and photographs of Nazi Germany, add emotional heft to George’s moving story.

An accomplished flautist, he was born in Oldenburg into an assimilated family that valued its German nationality more than its Jewish roots. In this sense, the Goldschmidts were hardly unusual in Germany’s patriotic Jewish community.

Such was their attachment to the fatherland that George and his wife remained in Germany even after the passage of the notorious 1935 Nuremberg laws, which deprived Jews of German citizenship and forbade sexual contact between Jews and ethnic Germans.

In that fateful year, George’s illusions were shattered when a professor at the academy in which he was enrolled brought him down to earth. He informed George, a promising student, that he had to leave the academy at once without a degree. His musical career in Germany was effectively finished.

At that shattering moment, at the age of 22, he decided to immigrate to Sweden. As he prepared for the journey, he was offered a job in Berlin as a flautist by the Jewish Cultural Association, an outfit which mounted concerts and plays for Jewish audiences. It was tolerated by the Ministry of Culture because it may have given some naive foreigners the completely false impression that Germany’s treatment of Jews was within the bounds of acceptability.

In fact, Jews were increasingly hounded and persecuted as Hitler consolidated his power.

These events form the substance of George’s conversations with Martin, who, inexplicably, is never seen on screen but whose voice is always heard. After telling Martin that he was expelled from the academy simply because he was Jewish, George says, somewhat surprisingly, “I never considered myself a Jew.”

“But you’re as Jewish as gefilte fish,” Martin insists.

“I’m not a fish,” replies George, abruptly ending the conversation.

Nonetheless, George tacitly acknowledges that he was foolish not to have left Germany after 1935. “I was trying to keep reality out,” he admits, even after he was at the receiving end of a humiliating encounter with a Gestapo official in Berlin.

With the outbreak of Kristallnacht, the nation-wide pogrom orchestrated by the Nazi regime on November 9, George belatedly knew his days in Germany were numbered. He immediately left his flat and boarded a train for Dusseldorf, where he met his wife and her similarly politically blinkered family.

They departed by train on June 1, 1941, bound for neutral Spain and Portugal, and arrived in New York City toward the end of that month.

They got out of Germany just in the nick of time. Had they postponed their trip by only a few months, they would have been forbidden to emigrate. In September, 1941, the Nazis closed the Jewish Cultural Association, sealing the fate of German Jews.

Like most new immigrants, they worked at menial jobs in the first few months in the United States. But after Rosemarie landed a position as a musician in a St. Louis orchestra, they moved there. For reasons never examined, George gave up music and worked as a furniture salesman until he moved to Arizona twenty one years later.

During one of their reconstructed conversations, Martin grows irritated by his father’s abandonment of his vocation as a flautist, claiming he had “wasted” his life as a salesman.

True or not, this is the fate that befell George Goldsmith, a German Jew who was born in the wrong place at the wrong time. Winter Journey distills the essence of his odyssey with sensitivity and compassion.